Cuts to US aid could end the Demographic and Health Surveys. This would leave a massive gap in our understanding of global health, mortality, and development.

If you were to die tomorrow, the details about your death — what you died from, your age, and demographic information — would very likely be recorded officially. Most countries have statistical offices that collect and report this data. This helps researchers understand causes of death, track trends over time, uncover risk factors, and identify emerging problems.

But every year, millions of people worldwide die without having these details recorded because of a lack of doctors, nurses, or functional vital registries. We therefore struggle to understand the burden of particular diseases, which interventions might save lives, and where to direct resources.

This lack of data directly affects low- and middle-income countries, but also limits the ability of other governments, researchers, and organizations to plan effective global health programs, assess the impact of aid, and ensure cost-effectiveness.

One key source that has filled this gap is the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). This is a program where large, nationally representative surveys have been conducted in over 90 lower- and middle-income countries1, roughly every five years, focusing on maternal and child health and mortality, but also collecting essential data on births, income and education, water and sanitation, and in recent years, diseases such as HIV and malaria.

The DHS program filled critical data gaps, provided an independent check on official records, and made estimates more reliable and transparent.

It was primarily funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and run by the American company ICF International. But earlier this year, the US government announced that it had terminated funding for the program. This threatens global health and development efforts and will affect many of the estimates we provide on Our World in Data.

Governments and international organizations will be in a much worse position without these surveys if they want to tackle some of the world’s biggest problems. However, it doesn’t have to end this way — there’s now an effort to rescue the DHS program, and new funders could help secure its future.

When it comes to basic, official data on populations — how many people are born, when they die, and what they die from — much of the world remains in the dark. Many countries still lack complete vital statistics, as shown in the two maps below.

In many parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, many deaths aren’t officially recorded. And even when a death is registered, we often don’t know the cause. In much of Africa, for example, most deaths happen without being registered at all. And among the ones that are registered, many don’t have a medical certificate or an official cause of death. In India, most deaths are registered, but most still don’t have a cause of death listed.

In a previous article, I wrote about why data on causes of death is missing in many parts of the world:

How are causes of death registered around the world?

In many countries, when people die, the cause of their death is officially registered in their country’s national system. How is this determined?

This lack of data reduces our understanding of global health. The chart below shows one example: during the COVID-19 pandemic, the global death toll — measured by excess deaths — was estimated to be three to five times higher than the number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths reported by countries.

Excess deaths are the number of deaths during a crisis beyond what we would expect under normal conditions. This measure captures both direct and indirect impacts, including unreported COVID-19 deaths and those caused by broader disruptions.

This estimate is especially uncertain in countries without mortality reporting. Globally, the margin of error is around ten million deaths in either direction. But even the most conservative estimates suggest the true toll was at least three times higher than the confirmed count.

One reason estimates like these are so uncertain is that statistical institutions are a relatively recent development in global history. Civil registries, population censuses, and national statistical agencies only became widespread in the last century, and they remain weak in many lower-income countries. Collecting rigorous data requires resources, systems, and staff that many poor countries today cannot support.

So, how do we know about health and mortality in these countries? For four decades, a major answer has been the Demographic and Health Surveys.

The DHS program was launched in 1984, originally to track fertility, but was expanded to cover more countries and a wide range of metrics.2

It surveys many countries where data from vital registration systems is incomplete. You can see this in the map below: most DHS surveys have been conducted in Africa, Latin America, and South and South-East Asia, the same regions where data was missing in the maps above.

In many ways, the DHS program has been an exceptional success. What sets it apart is its rigor and coverage. It has conducted over 400 nationally representative surveys across more than 90 countries, with large sample sizes — typically 5,000 to 30,000 households per country.3

It uses detailed, standardized training manuals, calibrated questionnaires, and strategies that reduce or track interviewers’ and respondents’ biases. The results are publicly available, making the DHS a consistent and trusted source of cross-country data.

In addition, the surveys have high participation rates, and since they include geographical data, researchers and analysts can track patterns at the local level.3

The DHS program collected core demographic data and focused on these crucial areas:3

Maternal and child healthNutrition and early childhood developmentFertility and family planningHIV and malariaDomestic and sexual violenceFemale genital cutting, child labor, and disabilityService availability, urban living conditions, household structure, energy access, and water/sanitationSome chronic diseases, injuries, mental health conditions, and out-of-pocket healthcare costsEducation and literacyCauses of maternal and child deaths in some countries, using verbal autopsiesIn many countries, the DHS program has been the only source of data

In many low-income countries, the Demographic and Health Surveys have been the only source of national data for some indicators.

The DHS program was, for example, the only underlying source on maternal mortality for 24 countries in the United Nations’ global estimates of maternal mortality. These countries are shown in the map below.4

These countries lack birth or death registry data, so the surveys have filled the gap. Without this data, researchers, public health experts, doctors, and policymakers would have very little idea of how many women are dying in childbirth, and why. It’s incredibly hard to make informed decisions in this darkness.

DHS data is used for a wide range of indicators, including by us at Our World in Data

The importance of the DHS extends far beyond the countries where it is conducted. Many researchers and institutions use it as a vital data source, and it feeds into nearly every major global estimate of development, health, and well-being.5 It’s also widely used to estimate countries’ population sizes and birth rates, which are used as denominators for many per-capita metrics. Researchers also use the data to study other key factors, such as age distributions, household sizes, and urban-rural breakdowns.5

On Our World in Data, much of our coverage of patterns and trends in lower- and middle-income countries relies on DHS data as a foundational source. Here are some indicators for which the statistical institutions we rely on use the DHS as a key data source. I’ve also included links to our work on each of them.

As a result, the DHS program allows our team to build better and more accurate visualizations of global patterns and trends. This would be very challenging with inconsistent or missing government records.

In 2025, the US government shut down the DHS program alongside other international health data initiatives.6

While this reduced US government spending by around $47 million per year, that’s a very small amount in relative terms: less than 0.1% of the total US aid budget, and 0.0007% of the total federal budget.7 But this decision has broad, long-term consequences. When the US cut its funding, surveys were set up or were already collecting data in 23 countries, which you can see in the map below.8

The data had already been collected in ten countries, but the analysis and reports were incomplete. This includes large countries like Nigeria, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. All the resources that went into setting up, conducting those surveys, and compiling the data will be wasted if the program doesn’t continue.

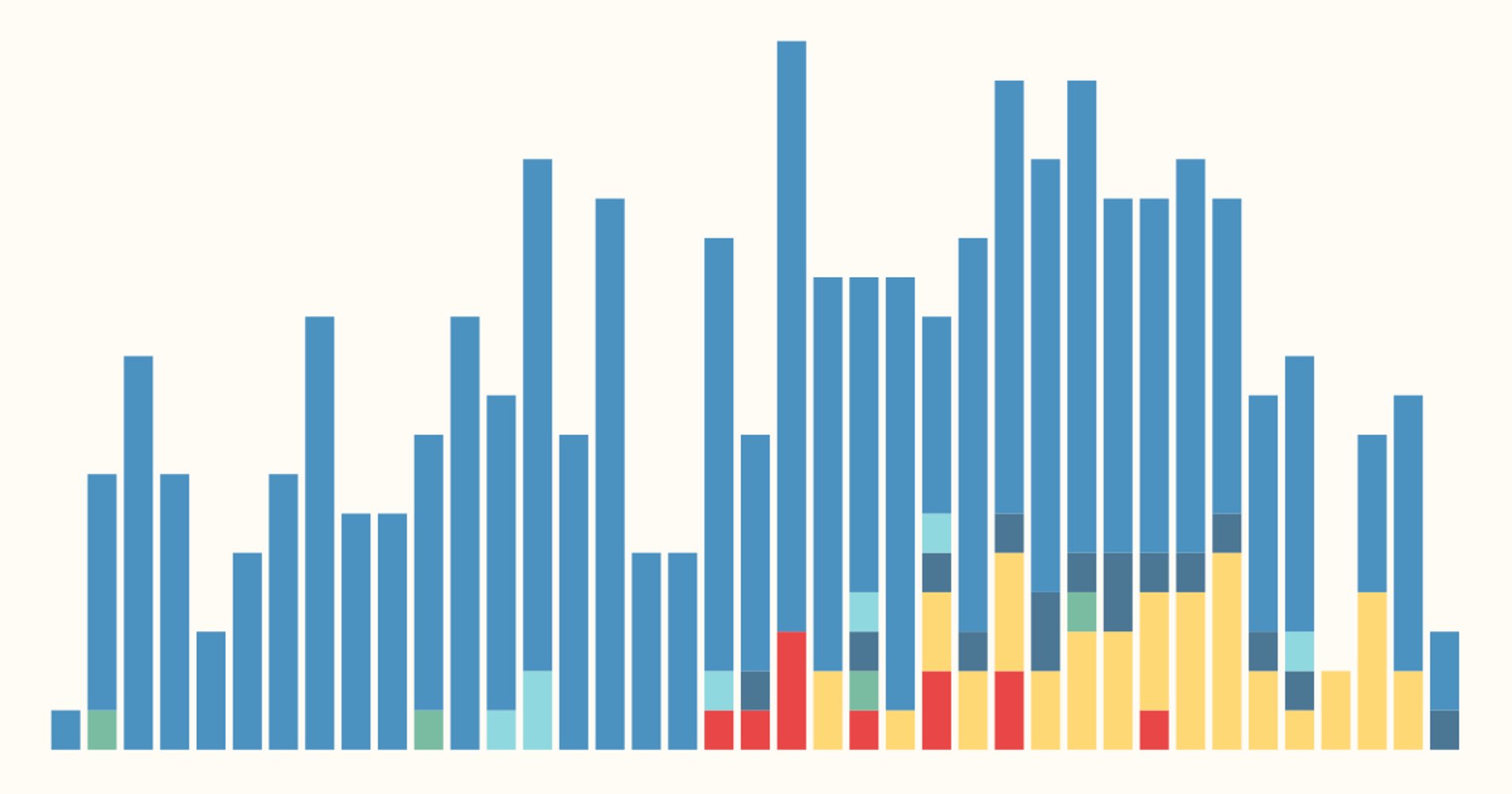

This comes on top of the disruptions that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic. You can see this in the chart below: the number of surveys dropped sharply during the pandemic, and recovery had just begun. Now, that pipeline is at the risk of being broken entirely.

Each uncounted life is a missed opportunity to better understand the world, to track progress, spot emerging problems, answer empirical questions, and direct resources efficiently.

To build a world where fewer people suffer or die unseen, we must invest resources in seeing more clearly. That means recognizing data collection as an intentional and vital act to improve the world.

The Demographic and Health Surveys showed that rigorous, large-scale data collection was possible even in the poorest parts of the world. Its loss shouldn’t be seen as inevitable. Reinstating the DHS program, or building something better in its place, is both possible and critical. If we care about saving lives, we should care about counting them.

The first step is to resume funding for the surveys that were underway. This would prevent the waste of years of planning, coordination, and investment.

The second is restoring the program for the long term. Sustaining DHS operations has cost about $47 million per year.9 That’s a tiny fraction of most national or international budgets, less than many single aid programs. But it’s likely still a large burden for one philanthropic funder alone.

This is a solvable problem, and many organizations have already started an effort to save it. More governments, foundations, and donors can join them and help secure this vital data source for the years to come.

Continue reading on Our World in DataCite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani (2025) – “The Demographic and Health Surveys brought crucial data for more than 90 countries — without them, we risk darkness” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/demographic-health-surveys-risk’ [Online Resource]

BibTeX citation

@article{owid-demographic-health-surveys-risk,

author = {Saloni Dattani},

title = {The Demographic and Health Surveys brought crucial data for more than 90 countries — without them, we risk darkness},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/demographic-health-surveys-risk}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.