SANDPOINTE, Idaho – Over the phone while making lunch in his Idaho home, you can hear Jim Czirr smile while recollecting his battle with two legends 50 years ago.

The St. Joseph native, now 71, is living out west helping fund anti-cancer drug development. His 70s era moustache no longer descends south of his lips, as he sports a clean shave and thin glasses.

But he was once a 235-pound Michigan football starting center who held his own in the 1976 Orange Bowl against Oklahoma’s Selmon brothers.

Lee Roy and Dewey Selmon were both consensus All-Americans that season, while Lee Roy is a college and NFL Hall-of-Famer on the Sports Illustrated “NCAA Football All-Century Team.”

Michigan lost 14-6 to the Sooners on New Year’s Day in Miami, leaving Czirr dejected. It wasn’t until the next night he realized how well he fared.

“This woman knew my name and told me how well I did,” Czirr said. “I thought ‘you must have blue and gold toilet seats in your home to think I did a good job.’”

“She then told me her husband Don Shula thought I did a good job against Selmon,” Czirr recalls, referencing the NFL Hall of Fame coach with the Miami Dolphins.

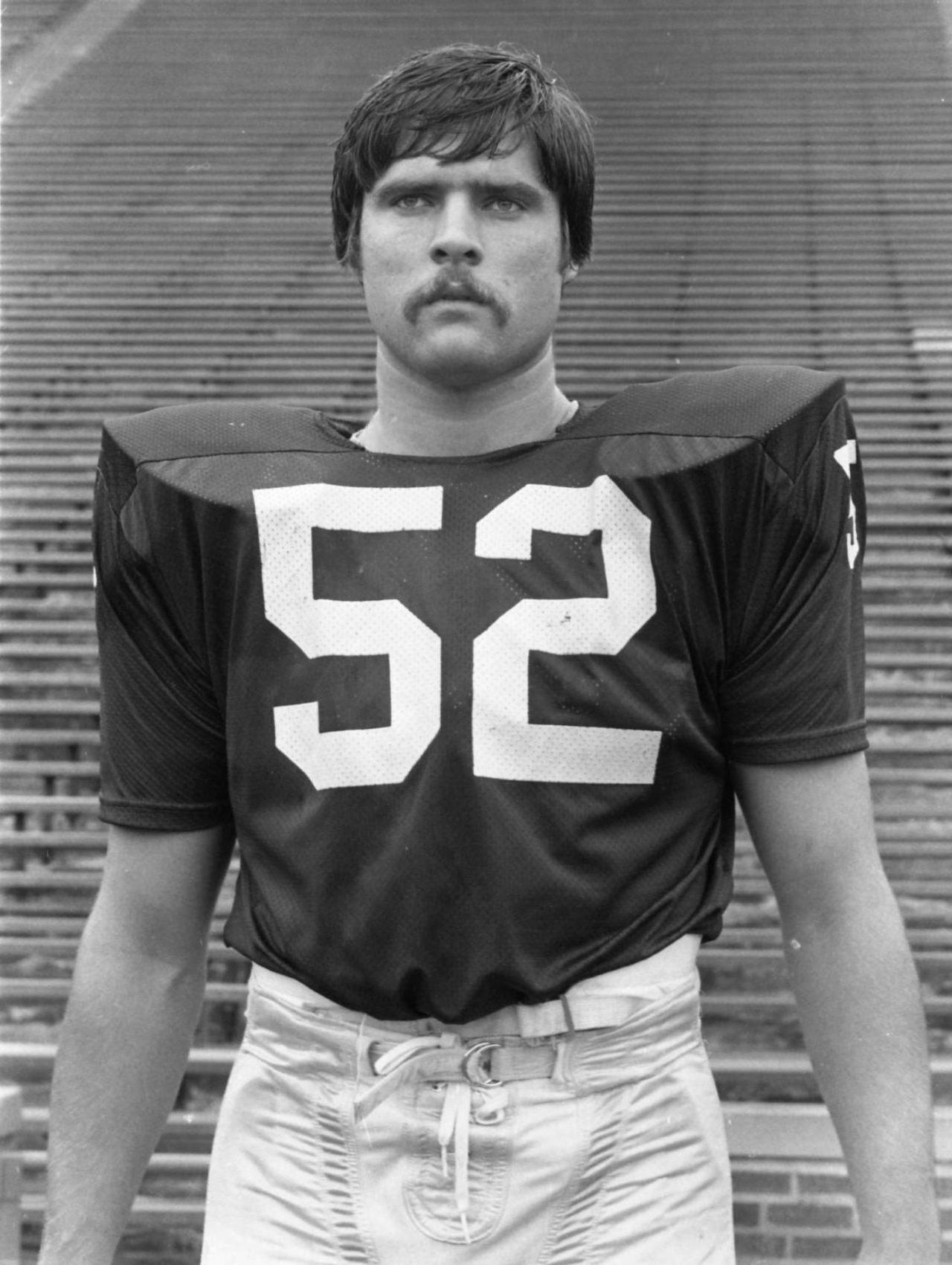

Michigan football center Jim Czirr in his 1975 team portrait. By his senior season, he was an All-Big Ten player and fared well against Oklahoma’s Lee Roy and Dewey Selmon, considered some of the best defensive linemen of their era. Photo provided with permission by the University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library.Bentley Historical Library

Michigan football center Jim Czirr in his 1975 team portrait. By his senior season, he was an All-Big Ten player and fared well against Oklahoma’s Lee Roy and Dewey Selmon, considered some of the best defensive linemen of their era. Photo provided with permission by the University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library.Bentley Historical Library

Before his Michigan football days, Czirr was a skinny offensive lineman out of St. Joseph High School. Smaller programs like Air Force and Navy offered him scholarships to play football, but he “didn’t have a lot of options outside of that.”

Late in his senior year, Michigan’s all-time winningest coach Bo Schembechler extended Czirr an offer. He thought Air Force would be the better fit at first.

“My dad was an Air Force guy,” Czirr said, adding programs like SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape) sounded fun.

But one night in front of a mirror while shaving, Czirr told himself: “You’re going to wonder if you were good enough to play at the University of Michigan.”

“Without knowing my major, I decided to go,” Czirr said.

Czirr also was drawn to Schembechler’s way with words. That is until he found his soon-to-be coach borrowed quotes from famous philosophers.

“Before I played for him, I was a naive high school kid,” Czirr said. “He used to say: ‘Whatever the mind can conceive and believe, it can achieve.’ I only found out later Bo stole the phrase from Napoleon Hill.”

Later in his life, Czirr joked with Bo that “he wasn’t quite as philosophical as I gave him credit for.”

Something Schembechler instilled in Czirr for the rest of his life was a sense of doing things the right way.

“Everything I’ve ever accomplished is due to the people around me,” Czirr said. “You always have a chance to win and focus on doing things right every day.”

Czirr struggled to bulk up throughout his college career, finally weighing enough his senior year to crack the starting lineup. He paved the way to the Wolverines cresting 300 rushing yards a game in 1975, earning consensus All-Big Ten honors from the conference’s coaches.

With an 8-1-2 record that season, the Wolverines earned a trip to the Orange Bowl against the eventual national champions in Oklahoma. For Czirr, it was his first time traveling for a bowl game. Despite Michigan amassing a 30-1-2 record his first three years, old Big Ten rules restricted the conference to sending only one team to a bowl game.

Czirr noted he should’ve traveled to the Rose Bowl after a 10-0-1 finish in 1973, but the conference held an emergency vote (which Czirr called “goofy”) after Michigan’s 10-10 tie with Ohio State to send the Buckeyes instead.

“It really was nice to go to Miami and finally play in a bowl game,” Czirr said.

The stakes were high: Michigan and Oklahoma became a de facto national championship game after No. 1 Ohio State and No. 2 Texas A&M lost their bowl games.

“If we had beaten Oklahoma, we would’ve been a giant killer on that day,” Czirr said.

The literally big problem: the Selmon brothers. In particular, Czirr drew the matchup with Dewey Selmon, the team captain with a few inches and 20-30 pounds on Czirr.

“He was all I could handle,” Czirr said. “This Selmon guy was a whole different degree than anyone I ever played against.”

One thing that helped Czirr is he said that something finally clicked with him on gaining weight. He said he bulked up 10 pounds before the Oklahoma game to deal with Selmon brothers.

Michigan ran the ball decently against the Sooners with 169 rushing yards, but Czirr said quarterback Rick Leach was off after a hit out of bounds that “would’ve been called targeting today.”

“That’s where we lost the game,” Czirr said, as Leach didn’t complete a pass until the fourth quarter.

His performance drew not only Shula’s eyeballs, but the NFL’s Denver Broncos. They drafted him in the ninth round of the 1976 NFL Draft, but he didn’t complete the season before moving on from football.

Czirr is now the president of the Washington-based financial advisory firm Sterling Pacific NW, LLC. He also co-founded Galactin Therapeutics, Inc., which develops drugs to combat chronic liver disease and cancer.

His time playing in front of 100,000 in Ann Arbor inspires his work today.

“I have this vision of filling Michigan Stadium with survivors,” he said.

Want more Ann Arbor-area news? Bookmark the local Ann Arbor news page.

If you purchase a product or register for an account through a link on our site, we may receive compensation. By using this site, you consent to our User Agreement and agree that your clicks, interactions, and personal information may be collected, recorded, and/or stored by us and social media and other third-party partners in accordance with our Privacy Policy.