Prof Des Fitzgerald first noticed something was off when a batch of sociology essays about the social construction of death all referenced Ancient Egypt in curiously similar terms.

“Nothing to do with anything I was teaching,” he recalls. “About the 10th or 15th time I came across the phrase, I thought, this can’t be a coincidence.”

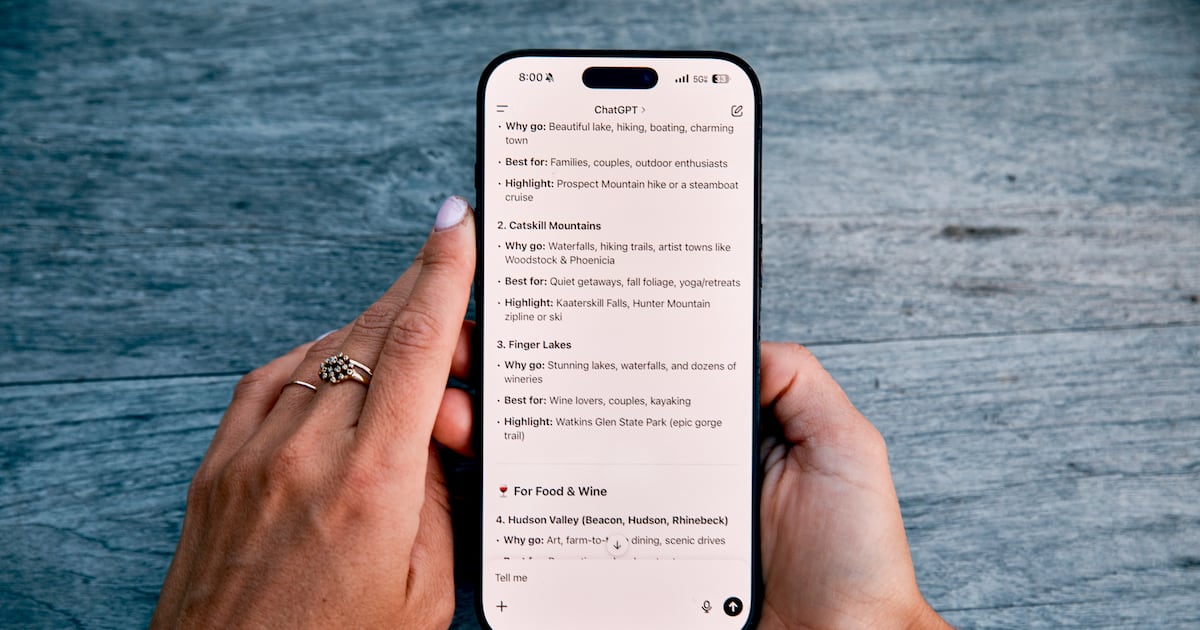

It wasn’t. The students weren’t copying each other, but using ChatGPT to brainstorm ideas.

“I haven’t set a take-home essay since,” Fitzgerald says. “I definitely felt like I’m not going to spend the next 30 years of my life marking essays, in some part written by machines.”

Instead, he now favours open-book, in-class essays moderated by a lecturer. This change has reduced the use of generative AI in his modules, but not eliminated it. “You can’t do it completely, but it cuts it down by about 75 per cent,” he estimates.

Fitzgerald also observes a quieter shift: students using AI to summarise assigned readings. “That’s the bigger issue. Even dedicated students who wouldn’t dream of plagiarising are certainly sticking PDFs into ChatGPT to get summaries.”

The problem, he notes, is not simply academic dishonesty, but what students lose in the process. “I want them to read something and engage with it for its own sake.

“There’s a joy in comprehension, that moment of understanding something new. AI robs them of that.”

In the age of generative AI, the written essay is facing an existential crisis. As tools like ChatGPT become widespread and sophisticated, lecturers across Ireland are reassessing not just how they teach and assess students, but what it means to think, read and write in a university context.

If the goal is the grade, why wouldn’t you use the tool that promises to get you there faster?

— Prof Des Fitzgerald

At Dublin City University, Michael Hinds, associate professor of English, shares the concern.

“It manifests as a kind of plausible, generic smoothness of language,” he says of ChatGPT-generated work. “But it’s soporific. It puts your brain to sleep.”

Rather than launching an arms race of surveillance, Hinds and colleagues have tried to re-centre learning. They hold communal film screenings and ask students to write about the experience of watching the film together. They encourage personal reflection in assignments, not just pseudo-objective analysis.

“We’re trying to bring back a sense of community to the idea of reading and writing,” Hinds explains.

Neither Fitzgerald nor Hinds is interested in demonising students. Both acknowledge the immense pressures many face, from high rent to long commutes to balancing part-time jobs.

“We had the time and resources to pull an all-nighter and really immerse in an essay,” Fitzgerald says. “They don’t.”

[ I am a university lecturer witnessing how AI is shrinking our ability to thinkOpens in new window ]

Suspicions about students’ use of generative AI are handled with quiet, often empathetic conversations. Photograph: Getty Images

Suspicions about students’ use of generative AI are handled with quiet, often empathetic conversations. Photograph: Getty Images

Instead, the crisis is seen as a systemic one. “There’s always been this tension,” Fitzgerald notes, “between pedagogy and credentialism. But when students have come through the Leaving Cert, which is hyper-grade-focused, it’s very hard to tell them that the point of university is something other than getting the best possible mark.”

This grade obsession and valuing outcome over process, over learning itself, is part of what makes generative AI so attractive to students. As Fitzgerald puts it: “If the goal is the grade, why wouldn’t you use the tool that promises to get you there faster?”

The response from institutions, however, has been inconsistent. While departments like Fitzgerald’s have instituted firm policies forbidding AI use unless explicitly allowed, others are more flexible. “It’s a rolling thing,” he says. “Different departments have very different approaches. That’s confusing for students.”

And even when policies exist, enforcement is murky. Both lecturers are clear: AI detectors are too unreliable and ethically fraught to be used. Instead, suspicions are handled with quiet, often empathetic conversations.

“Overwhelmingly, students are honest,” says Fitzgerald, who handles plagiarism cases in his department. “They’ll tell you what’s going on in their lives, why this felt like the only option.”

The technology makes things up all the time. Fake quotations, fake bibliography entries.

— Michael Hinds

At DCU, Hinds relies on identifying weak scholarship. “The technology makes things up all the time. Fake quotations, fake bibliography entries. That gives us a way in, but I presume we’re not catching everything.”

The deeper challenge lies in what both men see as the hollowing out of educational purpose.

“We’re not just credentialing people,” Fitzgerald argues. “We’re saying: we taught this person, they learned from us, they can think and argue and write. If the work no longer reflects that, then the whole edifice is in danger.”

What, then, is the future of assessment? The consensus is that universities must become more agile, more reflective, and more creative. Fitzgerald is considering oral exams and other forms of embodied assessment.

Hinds speaks warmly of students who write with openness and vulnerability, reflecting their own processes. “That’s the kind of writing ChatGPT can’t do,” he says.

Still, both recognise that these changes require labour, time, and money – resources not always afforded to precariously employed lecturers or departments facing budget cuts.

For part-time lecturers and tutors, who are often only paid for their time in the classroom, the expectation that they will overhaul syllabuses, design new assignments and adapt entire modules to new technological realities amounts to unpaid labour.

[ Students must learn to be more than mindless ‘machine-minders’Opens in new window ]

In the US, OpenAI made its premium service free for students around exam time. Photograph: Getty Images

In the US, OpenAI made its premium service free for students around exam time. Photograph: Getty Images

“That’s a really good point,” Fitzgerald says. “The institution isn’t always equipped to support the people doing the bulk of the pedagogical work. And it’s a huge amount of work.”

There is also growing concern about the ideological implications of these technologies. The fact that tools like ChatGPT are free – for now – is not incidental. “I really worry about the long game here,” says Fitzgerald.

“OpenAI’s strategy is to create bespoke GPTs for universities and even individual modules. I’m sure that will start for free. But eventually, you’ll find your entire pedagogical infrastructure is owned by someone else. Suddenly, we’re in hock to a massive organisation we barely understand and are completely at their mercy.

“We’ve already outsourced parts of our digital learning environments. But this is different. The university is supposed to be a public good. And these companies are trying to privatise that. They’re trying to make themselves indispensable, to get their hooks into the intellectual commons of the university and profit off it. That’s terrifying.”

For Hinds, ChatGPT doesn’t just present a logistical or pedagogical problem, but a symptom of something deeper.

“It exemplifies a much more manifest wrongness in the system,” he says. “It’s born of a model of education that’s transactional, instrumentalised, and competitive to the point of cruelty. It’s a monster, but it’s a monster born of a system that already wanted to destroy education as we understand it.”

This concern dovetails with a broader unease about the current political climate, particularly the rise of anti-intellectualism in tandem with the global rise of far-right ideologies.

In the US, OpenAI made its premium service free for students around exam time. Fitzgerald sees this as no coincidence. “I think we’re being sold something – for free – in order to make us dependent on it, to make it feel inevitable. But that’s a rhetorical trick. It’s not inevitable.

We need them to struggle with difficult texts and emerge changed. That’s the point. Not the grade.

— Prof Des Fitzgerald

“And giving up on the intellectual labour of reading, thinking, and writing because it’s easier or the future … that’s a capitulation. That’s anti-intellectualism disguised as innovation.”

And it’s a shift with political consequences. “The humanities are where people learn to think critically, to analyse systems, to question authority,” Fitzgerald says. “What happens if that disappears? What happens if you can simulate critical thinking without actually engaging in it? That’s not just an educational crisis. That’s a societal one.”

Still, both lecturers remain committed to their work and to their students. “We need their critical thinking skills, their beautiful thoughts,” Fitzgerald says. “We need them to struggle with difficult texts and emerge changed. That’s the point. Not the grade.”

For now, the battle continues – not against students, but against systems that make it harder and harder for both students and educators to do meaningful work.