The murder of Charlie Kirk struck me hard during the week. The symbolism of it was tragic for humanity. He was a man of words and they murdered him by shooting him in the throat.

When they had not the power of words to defeat him, they turned to violence and cut his words short. The symbolism of severing the throat of a Socratic debater is a message that seems delivered with intent to scare us all into silence! In a world where the will to power subsumes morality this is the inevitable culmination when you are losing the battle of words. His words could not be allowed win. His words were stopped with a bullet.

I was surprised when I asked my daughter about that that she said it was discussed a lot during the week in school. It seems the liberal viewpoint is to suggest he deserved it because of things he said.

One teacher listed off the non-progressive opinions that, according to him, Charlie Kirk had – opinions the teacher had decided were disqualifying. This sophist argument is lined up as justification for this act of extreme violence.

During the week you may have noticed some of these ridiculous lists of “sins” attributed to Charlie Kirk, which are supposed to be justification for his murder – for Kirk having “brought it on himself.”

“I don’t condone violence, but.” That “but” is very telling. It is the disclaimer of the slightly more intelligent leftists who don’t want to seem like complete monsters. But you would wonder; seeing as they know you might share opinions with Charlie Kirk, would they condone your murder for the same wrongthink?

The moral certainty of liberals, even up to the celebration of political assassination, is a sign of their spiritual sickness.

But it’s not this glaring moral putrescence – the celebration of violence over argument – that I wanted to discuss here. My colleagues have made this point very well here this week. It is our children and the conversations we have with them that is on my mind. As they are formed into our culture, who forms them? Is it their teachers, some of whom are shallow intellectually naïve herd animals spouting socialist resentment clichés; is it internet influencers; is it you?

If you don’t ask them what they discuss outside your home and what they absorb from the culture, and discuss it with them, you are not an influence on their life. They are forming, they don’t yet have the experience of the world, or the words, to engage these ideas in depth. Who will give them the words and the moral framework? They might have the instinct, but they need guidance.

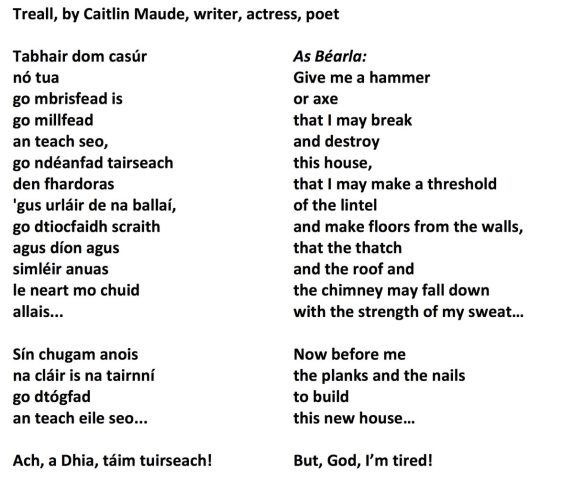

Every snippet of cultural material; of literature; of philosophical exploration; is a chance to bring reason and virtue and moral strength into your children’s lives. A few weeks ago, my daughter came home from school dissatisfied with the explanation her teacher gave her for Caitlín Maude’s poem, Treall.

Guess which teacher had his own ideological interpretation of it, and would not countenance any other interpretation? Yes, the same guy. Funny enough, the idea that there is no wrong answer in a subjective analysis of literature seems to be jettisoned if there is a preferable liberal/feminist answer. Why is that?

In brief, the class were asked what the poem was about. My daughter offered an interpretation. In her words: The author had rejected God, but when she found that she hadn’t the strength to build her own (metaphorical) house, she implored God for help.

“Nope” says teacher, who then rattled off an entirely predictable screed about how terrible Ireland was in the 1950s for women. ‘Women were not allowed to work, they had no rights, etc etc, et blah blah blah….

There was no other explanation. This was the right explanation, my daughter was wrong.

By the way, one of the grave moral errors Charlie Kirk had, according to this teacher, was that he was against abortion and women should be allowed to choose for themselves.

Maybe teacher should review ‘The Century of The Self’.

So we looked at the poem together, and instead of analysing it through a lens of pre-ordained cultural dogmas, we looked at the words. Without trying to impose our own ideological interpretation onto the poem we looked at what was written; the choice of words, the structure, the narrative, the metaphoric statement.

The poem is structured in three paragraphs. Each contains a statement. The first paragraph consists of short staccato lines. A rapidity of syllables beating a rhythm, creating a sense of momentum. There are three parts to the statement. “Give ME a hammer… That I may make… That the thatch… MAY FALL.”

If we look more closely we can see that the rhythm is beaten by a rapid consonance-based meter. The stressed counterpoint in the words “go mbrisfead, is go milfead” landing hard on those final “d”s inserts a momentum that brings alive the visual action of this act. Action and momentum, feels like purpose.

In the 8th line she employs the same technique again. Read out the phrase “gus urláir de na ballaí” and notice that consonantal rhythm again. The three stressed sounds at the beginning of “de na ballaí” –the “d” the “n” and the “b” how they infuse a rhythm into this description of action.

But all this action is impulse. It is the desire to pull apart.

In the second paragraph the meter and the alliterative emphasis changes. The stress in the rhythm shifts to the vowels. Read the opening line “Sín chugam anois” and you notice that the phrasing is now melodic. The stress on the long ‘í’ in sín. The soft, almost silent g in ‘chugam’ leaving this word an arching soft musical phrase based on the phoneme of the open ‘u’ transforming into broader ‘a’ and finishing with the resonant ‘m’. It’s like the striking of a tuning fork.

The next line stresses the vowels again “na cláir is na táirní”. This alliteration of the long “a” and the “r” stretches the rhythm again and that beaten rhythm of the first part is replaced by unstressed arching phrases. The effect is to bring a contemplative mood. The action of the first paragraph is arrested by a more thoughtful mood; one that indicates a vision; an awareness that that purpose of the first paragraph has to be married to a vision. What will we build with this vision?

The poem finishes with a short envoi “ach, a dhia, táim tuirseach” that brings more questions than answers.

Again we see a change in phrasing. The alliteration emphasis in “táim tuirseach” is on the ‘t’ but also on the long vowel that follows. The sentence’s meter is broken into three phrases by the two commas, bringing a sense of disruption. This stuttering meter brings a feeling of uncertainty into the phrase. The vision was not sustaining.

“But, God, I’m tired.” Is this a post-Christian statement? This is where the author brings ambiguity into her lines. We can’t tell what she means by this. Was my daughter right? In this phrase did she lose faith in herself –“the strength of my sweat…” and ask God for succour?

Why does she use this phrase? Does she have faith in God, or is she only using the words and phrases of her tradition? Has she rejected her past as my daughter’s teacher had asserted with such certainty? The words don’t imply it. The structure does not imply it.

If we look into a deeper layer of structure and the language of modernity, we can interpret the layout of the poem as a rejection of traditional form; as a post structural poem.

The argument can be made that Maude is using the feminist trope “for the master’s tool will never dismantle the master’s house” – a disingenuous axiom coined by neo-marxist feminist Audre Lorde (who, by the way, used her critique of the “masters house” to get a very comfortable sinecure and controlling seat in the “masters house”) – but the narrative of the poem does not imply this intersectional-feminist narrative.

Also Lorde delivered the idea of this essay for the first time during a speech in 1979, so it does not predate Maude’s poem which was written in 1963, and therefore couldn’t have influenced it.

We also know that Maude was not primarily a feminist activist. Her passion was the Irish language and she was heavily involved in the Cearta Sibhialta na Gaeltachta campaign. This was a woman who expended great passion and energy on preserving tradition not on tearing it down.

From this point of viewing, it seems more likely that if this was a commentary on her own political activism, it may have been a commentary on her frustration in a lack of progress of the Irish language movement. Perhaps in calling out to God for comfort she was looking for strength from without – from tradition and faith – rather than from her own will.

I think that my daughter’s interpretation, instinctively felt, was a better interpretation than her teacher’s. I think she was on the right track, because she examined the words and did not try to fit the poem into her own preferred ideology. This is what the search for truth is.

I know an Irish language poem on the Junior cert is not a world-changing subject but it is still important to use opportunities like this for conversations with our children.

Destruction and violence is much easier than building. Reactionary unreasoned responses might seem satisfying in the moment, but they cannot sustain without vision. A vision takes reason and virtue. These are either nurtured or rejected. These are built from first principle. They are the foundation stone of culture.

We can have a culture of death or a culture of reason. We build this with the next generation; with our children. There is no third way.