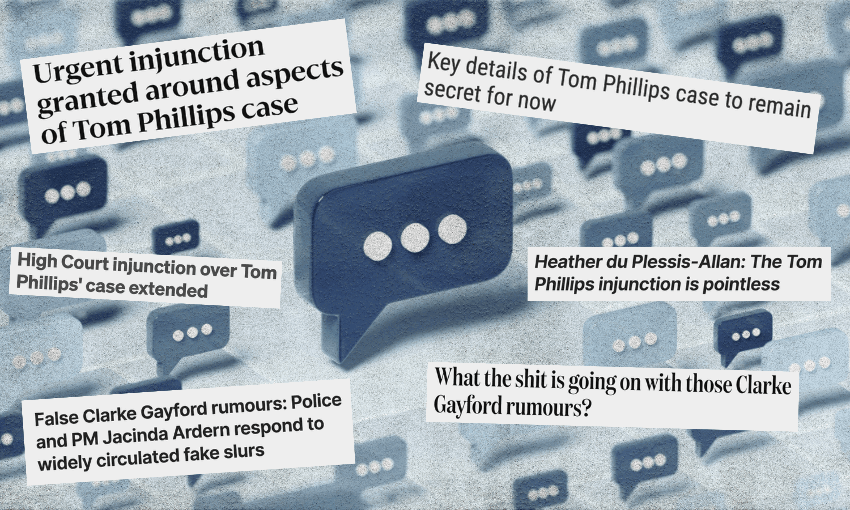

Responding to intense speculation spreading on unregulated social media platforms in the past has put authorities in a bind now.

It was early May of 2018, and despite having a fresh government and telegenic prime minister, there was only one subject on our minds. Conspiratorial allegations swirled relentlessly about prime minister Jacinda Ardern’s partner Clarke Gayford. Facebook was riddled with them, and they were persistently discussed in pubs and supermarkets too. Ultimately NZ Police felt compelled to take the “extraordinary” step of issuing a media release denying the rumours had any factual basis.

The stated justification was a suspicion that the rumours were politically motivated – but in any case it started something of a trend, whereby social media-powered rumours met with official denials. Two years later, then health minister Chris Hipkins addressed a press conference in August of 2020, to deny rampant online speculation suggesting a recent Covid-19 outbreak was caused by clandestine visits to managed isolation facilities. This set a pattern throughout the pandemic, with rumours flying about five children collapsing after vaccination and sex workers sneaking across the border to Northland, among numerous others.

In most cases, once a particular level of ubiquity was reached, some part of our institutional apparatus whirred into action to deny the story, or refine it. This even happened in reverse at times, with Hipkins having to correct the record – the sex workers in Northland weren’t sex workers at all, and had legitimately issued travel papers.

What all these episodes have in common is a sense that once a rumour has sufficient velocity and distribution, it’s dangerous to have it go unchallenged in the public arena. The public denial has become a familiar part of the narrative when major news events collide with widespread speculation.

Except when no denial occurs.

The Tom Phillips case had transfixed the nation long before it reached its tragic conclusion in the early hours of last Monday morning. The way it ended ensured that it would be the only domestic story of the week, with saturation coverage across our news sites addressing every conceivable angle. Yet almost as soon as the facts emerged, so did an injunction preventing reporting of “certain details of the case”.

Just as it does with name suppression, the injunction had the Streisand effect of further piquing already immense public interest. Seemingly within hours, a very specific and appalling rumour began circulating. I first received it via text, then heard it from a friend, who’d heard it from a reporter, who heard it from a journalist on the ground near Marokopa. None of this makes the rumour true; anyone who has worked in news media for a while will have heard sensational stories that never stand up.

This one kept going, though. I saw the parents of a friend later in the week and it was the first thing they spoke about. An overseas news outlet reported the speculation, before pulling it down, serving only to amplify it. Social media, particularly TikTok and Meta’s platforms, are riddled with the claims. (Interestingly Reddit, which has long had a culture of volunteer moderation, has been far more circumspect).

These situations are particularly challenging for news media. If rumours are false and the media refutes them, they’re still being repeated, which brings legal jeopardy even if the reporting contains an explicit denial. Yet when rumours are so widespread, to not report on them breeds mistrust: what are they hiding? And why?

Police minister Mark Mitchell and police commissioner Richard Chambers during a press conference after the police shooting of Tom Phillips (Photo: Dean Purcell/New Zealand Herald via Getty Images

Why haven’t we been told?

The pressure builds. Newstalk ZB’s Heather du Plessis-Allan wrote an incendiary column for the Herald on Sunday yesterday that got close to confirming the rumours, without naming them. “One day when some streaming service like Netflix – inevitably – does a hideous, invasive ‘documentary’ [the allegation will] be either the opening scene or the twist at the end.”

She used this to argue for greater disclosure. “I lean towards believing the injunction should be lifted… Because it allows at least some questions to be asked and answered. It allows the man to be assessed completely.” She argues, persuasively, that injunctions and suppressions can feel like relics of a different era, one before smartphones and social media and generative AI.

That is true. Yet it’s also true that our institutional reaction to prior episodes of rumours flying on social media has put authorities in a very awkward position here. By persistently issuing denials, we have created an expectation that we will be told when something isn’t true. If we’re not told, by implication, we’re much more inclined to believe it.

I reached out to NZ Police on Friday, to ask under what circumstances they issue comment rejecting online speculation, and for any documentation that existed to frame up such a decision. At time of publication, I have received neither acknowledgement nor reply.

In many ways, I understand. They are in a tough bind. The case itself will be scrutinised and second-guessed for years to come. If true, the rumours cast a harsh light on the softly, softly approach of police throughout. This can’t help but be front of mind for police communications staff.

More to the point, they’re as bound by the injunction, which has now been extended to September 18, as we are. But as du Plessis-Allan suggests, with each passing day the rumour feels more solid, and the injunction more feeble. Into the void, speculation rises. Even Mark Mitchell’s statement that Phillips was “a monster” can be read as a nod at something darker than has currently been reported.

That is in no small part due to social media, which our authorities appear to have all but acknowledged as being wholly ungovernable for a state of our size and power. That remains a stain on our sovereignty, one with consequences ranging from endemic scam advertisements involving public figures from the prime minister on down, to a fast-eroding tax base due to the tech giants’ epic profit shifting.

But in this instance, our institutions have to wear some share of the blame too. Starting with the Gayford case, they established a precedent for making comment when they considered rumours to be sufficiently widespread and dangerous. It made sense at the time, and did have the effect of cauterising that lengthy period of wild speculation. Yet it and future denials unavoidably created an expectation that authorities would step in when speculation reached a sufficient volume.

It didn’t seem to imagine a future situation when such rumours might be true, while still needing to be kept from the public eye. Even if that turns out not to be the case in this instance – and we may never know either way – it will be some day. At least until social media companies are made as responsible for what they publish and distribute as other media have always been.

Due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter, the comments function has been disabled on this post