The outpouring of support for the Marokopa fugitive reveals several pervasive myths about masculinity, fathers and the court system, writes Alex Casey.

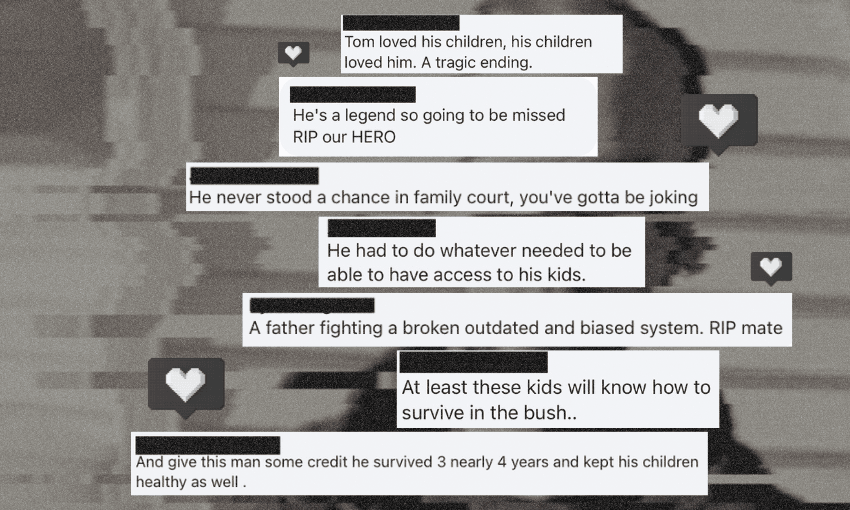

You don’t have to look very hard on social media to find support for Tom Phillips, who took his three children into the dense native bush amid a custody battle in 2021, and managed to evade authorities until he was killed by police during a shootout in rural Waikato last week. “To survive for 3-4 years with 3 kids in the bush speaks highly of the man,” one commenter wrote. “R.i.p big fellah, what you did was awesome in my eyes, true love for your kids,” said another. “A desperate dad, who lived and died for his kids, a legend.”

Following his death, authorities were quick to condemn those glorifying Phillips’ actions online. Police commissioner Richard Chambers told the public that he was “no hero”. Mark Mitchell, police minister, used even stronger language. “He has kept them [his children] away from education. He has kept them away from medical support. He has taken them and used them as human shields in violent criminal offending” he said. “This guy is in no way, shape or form a hero. Quite the opposite – he’s a monster.”

Carrie Leonetti, associate law professor at the University of Auckland, says she is concerned by the amount of people who continue to praise Phillips’ actions online. “I’m pretty alarmed that a guy who abducted his children for four years, cut them off from everything and everybody they know in the world, then shot a cop in the head on purpose, would be considered a hero by anyone,” she says. “You never know from internet posts what percentage of people are actually represented by these views, but we know for a fact it’s not zero.”

Carrie Leonetti, associate law professor at the University of Auckland.

In fact, some comments praising Phillips have garnered hundreds of likes. “He had to do whatever needed to be able to have access to his kids,” wrote one commenter. “I’d say about 85% of the country was on his side,” said another. “He was just a desperate man tryna keep his kids safe.” There are countless more that paint a picture of a wronged father fighting for his rights, a man who just wanted to spend time with his kids. “The system drove him to that,” reads one. “Push a man to a place of desperation, and see how desperate his actions become.”

Having spent the last five years researching the Family Court and specifically private custody proceedings in Aotearoa, Leonetti says there are several pervasive myths driving the pro-Phillips response. The first she calls a “cult of masculinity” that centres the importance of fathers over mothers. “There’s this really strongly held belief in our society that being raised by a single mother is inherently bad for children, and that having an active, involved father is inherently better – no matter how violent or abusive that father might be,” she says.

What also helps feed into that myth in this specific instance, says Leonetti, is the fact that Phillips’ children were reportedly found “well and uninjured” after four years in the bush. “People don’t understand psychological abuse, coercive control, isolation, intimidation – there are many studies on children who are abducted by a parent that prove it causes devastating, long-term consequences,” she says. “Even though there’s no known evidence of any physical forms of violence against these kids, what he’s done is probably going to cause far more damage.”

Mainstream media vs social media

What is also stark in this support is the absence of compassion for the children’s mother. “We take men’s suffering and men’s hardship much more seriously than we take women’s suffering and women’s hardship,” says Leonetti. “That’s why there has been this outpouring of empathy for Phillips and this narrative about ‘poor guy was going to lose his kids’, but no corresponding empathy to the fact that their mother actually did lose her kids for four years. It’s like men’s potential suffering is tragic, and women’s actual suffering is just our lot in life.”

Another narrative that is returned to often online is that Phillips was a man trapped in a broken Family Court system, one that roundly discriminates against fathers (“this guy is an example of how the custody system only serves women” is one example). In actuality, Leonetti points out the last two reviews by the United Nations have found systemic gender discrimination against women in our Family Court, and notes there have been repeatedly raised concerns around what she calls a “hostility” to women going through the courts who’ve experienced violence.

One well-documented recent example of this is the case of Mrs P, who served a year of home detention for perjury after being wrongly accused of lying about her domestic abuse by the Family Court. Despite providing ACC records that showed she sought treatment for sexual and physical abuse inflicted by her husband, Judge Peter Callinicos ruled that she had “fabricated” the reports. “He gave the man that abused me a piece of paper that he could show everyone that said he didn’t do it,” Mrs P told Stuff in 2021. “The judge made him the victim.”

Leonetti also notes that what seeps in through both the online comments and the Family Court system itself are “pervasive, nasty, misogynistic stereotypes” about “vindictive, manipulative women” trying to take children off their father. “Why does this absolutely unfounded myth that the Family Court somehow always sides with women and always harms men have so much traction? Because it resonates with underlying stereotypes,” she says. “It’s familiar to us, because it’s the baggage that we all carry around by growing up in a sexist society.”

Of course, sexism goes well beyond the internet comments and well beyond the courts. “This is a New Zealand problem. This is a culture problem. We have a problem with women, and we have a problem with misogyny,” says Leonetti. “And now we are in the manosphere, and the internet has become an incubator for men to launch these grievances that they are systematically discriminated against.” And while reading through the comments can be an “unnerving” experience, there is value in being able to see it and name it for what it is.

“Well, shit,” she says. “At least we now know what used to be whispered in dark rooms.”