Michael Feeney Callan, Robert Redford’s biographer, remembered escorting the actor and film-maker, who has died in Utah at the age of 89, to Le Caprice restaurant in south Dublin some years back.

Despite pulling a beret over his famous brow, Redford was spotted by the singer Dickie Rock, who sauntered over to the piano and launched into The Way We Were. Callan, recognising the song as the theme to one of Redford’s big hits, apologised to his guest.

“I winced, but Redford loved it,” the author later wrote. “Dickie waved. Bob waved back. ‘Soundtrack of my life,’ he said. And the beret came off.”

Not quite his whole life. Redford, born in Santa Monica, California, had the usual struggles as a young actor. He secured a few smaller parts in the late 1950s and early 1960s. His role as a wounded cop in a 1962 episode of The Twilight Zone still pops up on television. A degree of security came when he was handed the lead in the original 1963 Broadway cast of Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park. The film version of that play four years later kicked him a few rungs further up the ladder.

But it was the run that began with George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, in 1969, that made him, then in his 30s, the biggest movie star of the era. Classics such as Jeremiah Johnson, The Candidate, The Sting and All The President’s Men followed.

The legend goes that virtually every actor of note rejected an offer to play Sundance opposite Paul Newman’s Butch. Jack Lemmon, then well into middle age, was a first choice, but, perhaps wisely, he felt it wasn’t right for him. Steve McQueen and Warren Beatty were also in the frame.

Who among those could have so casually embodied the promise of the character’s name? Redford brought a shaft of California sunlight across a nation – and a world – that was moving into social and economic uncertainty after the turbulence of the 1960s.

He was suave. He was witty. And he was impossibly handsome in a fashion only Americans could manage. (No simmering Frenchman or cut-glass Englishman he.) “You can’t play a loser,” Mike Nichols said to him when turning him down for Dustin Hoffman’s role in The Graduate. “How many times have you ever struck out with a woman?” The director later claimed that Redford looked baffled and said: “What do you mean?” Nichols believed that “he didn’t even understand the concept”.

[ Robert Redford: US actor and Oscar-winning director dies aged 89Opens in new window ]

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a light-hearted buddy western, was just the mainstream salve the public needed as Vietnam boiled. Nichols has a point about Redford not playing losers. Even when things were going badly for his character – the terrified low-grade CIA employee in Three Days of the Condor, the bumbling politician in The Candidate – the audience always suspected he would pull through. Nobody who looked like that was likely to remain long on the canvas.

The actor, director and activist Robert Redford has died at the age of eighty-nine at his home in Utah.

Two films in the mid-1970s marked the zenith of his acting career without heralding any dramatic tapering off. He reunited with Newman and the director George Roy Hill to play one of two conmen targeting a malevolent Robert Shaw in the hugely popular The Sting. That film won best picture at the 1975 Oscars and secured Redford his only acting nomination. (He lost to Lemmon for the near-forgotten Save the Tiger.)

A year later he was disingenuously charming as Bob Woodward opposite Hoffman’s Carl Bernstein in Alan J Pakula’s All the President’s Men. It was canny casting. Redford’s white-bread wholesomeness, set beside Hoffman’s more aggressive style, lures more than a few sources into complacency as the journalists untangle the Watergate scandal.

[ Robert Redford 1936 – 2025: A life in picturesOpens in new window ]

It is of no value to point out that his star wattage declined in the 1980s. Only Tom Cruise has managed the hitherto impossible task of remaining an unaltered romantic lead over 40 years. Redford stayed enormously famous and lit up decent pictures such as the dreamlike The Natural, from 1984, the outrageous Indecent Proposal, from 1993, and, as recently as 2018, David Lowery’s lovely The Old Man & the Gun.

By the early 1980s he had, anyway, already begun a distinguished career as director and facilitator. There was some ill feeling among pointy-headed cineastes when, in 1980, Redford’s Ordinary People beat Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull to best picture at the Oscars, but that searing bereavement drama – featuring touching turns from Donald Sutherland and Mary Tyler-Moore – has weathered the decades better than many of the era’s winners.

In the early 1980s he helped fund the Sundance Institute, a body dedicated to the development of independent artists, and ultimately became the face of the Sundance Film Festival, in Park City, Utah. Redford can reasonably be viewed as a godfather of the indie movement that changed the industry through the 1990s. Film-makers such as Quentin Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, Steven Soderbergh and Ireland’s John Carney received early boosts at the festival. Few other movie stars of Redford’s era made such generous use of great fame.

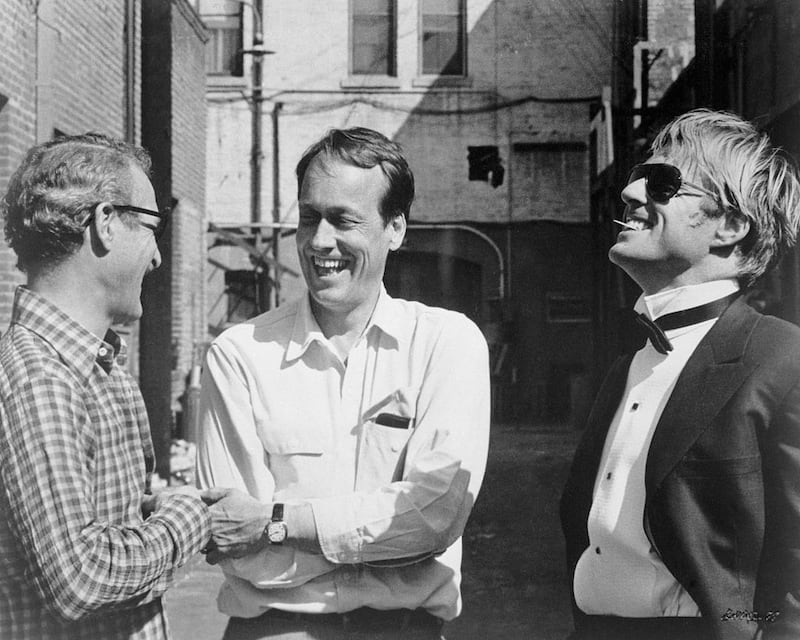

Paul Newman, director George Roy Hill and Robert Redford on the set of The Sting (1973). Photograph: Getty Images

Paul Newman, director George Roy Hill and Robert Redford on the set of The Sting (1973). Photograph: Getty Images

He remained famously good company throughout a long life that began humbly enough as the son of an accountant. “If I asked [my grandfather] what his father’s name was he’d say he didn’t remember,” he told Tara Brady, now of this paper, in Hot Press 18 years ago. “And if I asked him about my Irish roots he’d just say they were dope addicts and horse thieves. They had a great sense of humour, though.”

Despite being a contender for the best-looking star ever, Redford was not much in the gossip pages. He married Lola Van Wagenen, a historian, in 1958 and they stayed together until a quiet separation in the early 1980s. They had four children, two of whom predeceased their father. In 2009 he married his long-term girlfriend Sibylle Szaggars.

Redford died as one of the true supernovae. A Gary Cooper. A Cary Grant. A Gregory Peck. “One of the lions has passed,” Meryl Streep, who starred opposite him in Out of Africa, mourned. “Rest in peace my lovely friend.”