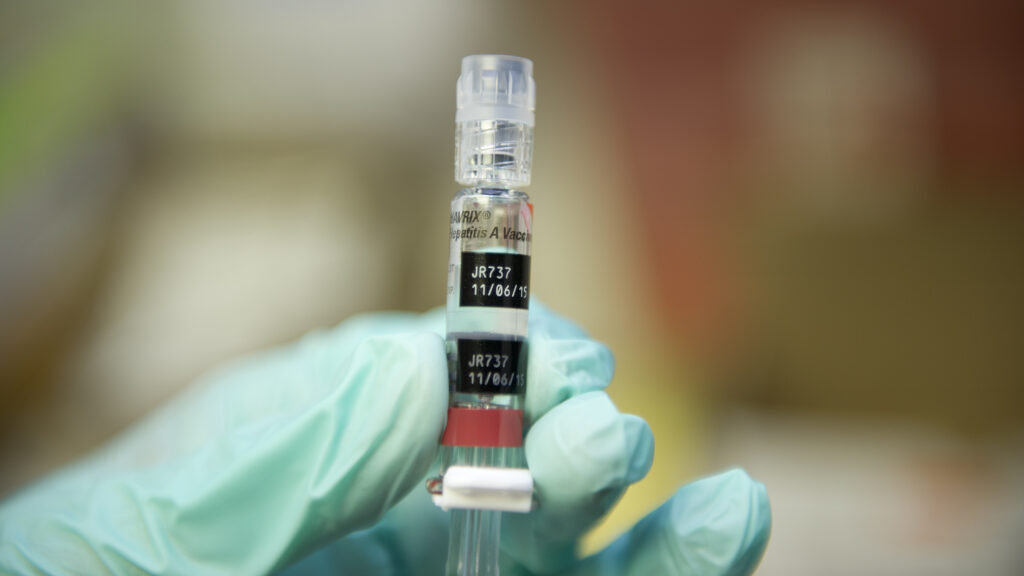

A key government advisory committee discussed on Thursday whether to recommend delaying the first hepatitis B vaccine shot, currently given at birth, by at least one month for babies who are born to mothers that test negative for the virus. Experts fear such a change could set back decades of public health work that has almost eliminated infant hepatitis B cases in the U.S.

The members of the Advisory Committee on Immunizations Practices pushed a vote on the issue to Friday. Experts fear that if ACIP does shift the initial shot, more children will develop chronic liver infections and complications.

An HHS spokesperson told reporters that the hepatitis B vote was delayed while a “discrepancy” in the recommendation is aligned with language about how the vaccine is covered by the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, which provides low-cost or free vaccines for about half of the children in the country who are uninsured or on Medicaid. Officials did not specify how they’re going to address the discrepancies, or what a fix might look like.

The spokesperson added that the vote was moved to ensure anyone who wants the hepatitis B shot can get it.

At Thursday’s meeting, the committee also voted 8-3 (with one member abstaining) to recommend that children under 4 receive the measles, mumps, rubella vaccine and varicella vaccine separately, rather than receiving the combined MMRV vaccine. The CDC has already said that it prefers this first dose be given as two separate shots, as there is a very small but higher seizure risk when giving the first dose combined.

However, several committee members were stumped by a subsequent vote that would align the recommendation with language in VFC. Aligning the recommendation would cut off access to combined-dose MMRV vaccines for children covered by VFC, alarming several members who launched into a tense debate about whether they should cut off coverage for only some children — at odds with the message of parental freedom that many had promoted during the meeting. Ultimately, the change was rejected, creating an uneven coverage pathway, in that private insurers and some federal health programs will no longer be required to cover the combined shot while VFC must continue to do so.

Following the meeting, ACIP Chair Martin Kulldorff would not answer questions by reporters on why the MMRV votes had splintered, but he did defend the vote as a means to improving trust in overall vaccination. “If we want to maintain integrity for the vaccine schedule, we both need to minimize adverse reactions,” he said.

However, public health experts say the votes have further sown chaos in how the public views vaccination.

“Instead of emerging with clear guidance about vaccines that we know protect against serious illnesses, families are left with confusion, chaos and false information,” Susan Kressly, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, wrote in a statement after the meeting. She added that AAP’s vaccine recommendations have not changed.

Jake Scott, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford University, said that while many parents already have their children take the first dose as separate shots, the risk of seizures of the combined shot is still very low. Revisiting the long-standing MMRV vaccine when there are no new safety concerns “really does undermine confidence and potentially in our entire immunization program,” he said.

The way the committee ultimately voted “creates this bizarre situation where the federal program will pay for a vaccine the same committee says couldn’t be given,” and that puts providers in an impossible position of trying to explain the recommendations to parents, he added. It “undermines the whole scientific credibility of the decision and will only create more confusion for families and providers.”

Experts had been bracing for an upheaval to the childhood vaccination schedule after health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. earlier this year fired all previous members of the ACIP and handpicked the current members.

‘We’re going to miss the most vulnerable’

The recommendation to vaccinate newborns for hepatitis B came in 1991, after vaccines had been available for nearly a decade for high-risk people but had yet to decrease the infection rates. Following the recommendation, hepatitis B cases in children and teens dropped 99%.

Dropping hepatitis B shots for newborns would ignore history and endanger children, scientists warn

Giving newborns their first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine almost immediately helps ensure that they don’t contract the disease from their mothers. While pregnant people are recommended to be screened for hepatitis B, some don’t receive prenatal care, and others may get hepatitis B after being screened. It also helps prevent babies from getting infected from anyone else they come into contact with, as the pathogen is highly contagious and can be passed on through small specks of blood.

There is no cure for hepatitis B, and if an infant is exposed to the virus and develops a chronic liver infection, that could then lead to liver cancer or the need for a transplant.

If the first shot is pushed back, “we’re going to miss babies, we’re going to miss moms, we’re going to miss those who are most vulnerable,” Chari Cohen, president of the Hepatitis B Foundation, said in an interview. “We’re removing the safety net essentially.”

ACIP’s recommendations influence how physicians practice and help determine health insurance coverage. The country’s main association of health insurers announced on Tuesday that its members will still cover all vaccines that were recommended before this week’s ACIP meeting, even if those recommendations change, through next year. But even then, a vote to delay the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine could create a confusing landscape for physicians and for parents seeking information on vaccinating their children.

Debating the hepatitis B vaccine

During Thursday’s meeting, ACIP members were repeatedly asked by observers why the committee had decided to revisit the long-standing practice of giving a birth dose.

Member Robert Malone, who questioned whether there’s enough data on the safety of the vaccines, said he thought the comments from observers were “disingenuous.”

“The signal that is prompting this is not one of safety, it’s one of trust, and it’s one of parents uncomfortable with this medical procedure being performed at birth in a rather unilateral fashion without significant informed consent at a time in particular when there has been a loss of trust in the public health enterprise and in vaccines in general,” he said.

The analyses presented to ACIP by CDC staffers showed that the hepatitis B vaccine is safe and effective, but several members questioned that data and said there’s a lack of research on the long-term safety of hepatitis B vaccines. Member Vicky Pebsworth pointed to higher rates of irritability and fussiness observed in babies who received the vaccine and said that “they may be early symptoms of neurologic problems that will need to be followed up.” CDC studies have not found any increased risk of neurological problems.

Two members, Cody Meissner and Joseph Hibbeln, pushed back on that sentiment and spoke out in favor of the vaccines. In response to Pebsworth’s comments about fussiness and fevers, Hibbeln said that “these might be indicators, but they might not be indicators, and we can’t vote on speculation.” He added that “we have to vote on where there’s data of concrete harm or concrete benefit.”

Hibbeln also noted that newborns are at risk of infection not only from their mothers, but from anyone else they come into contact with, so he questioned why the group would stratify its recommendation based on the status of the mother.

“We will increase the risk of harm based on no evidence of benefit, because there will be fewer children who will get the full hepatitis B vaccine series,” Meissner said during the discussion. “It’s an extremely safe vaccine, a very pure vaccine. So I think we will be creating new doubts in the mind of the public that are not justified. There is no evidence of harm from administering the neonatal vaccine that I’ve heard presented or that I’m aware of from my readings, so I would be concerned if we were to change the recommendation for that neonatal dose.”

In advance of the vote, the CDC posted a rapid systematic review of the evidence on the effects of the vaccine. The review on potential side effects included eight studies and found a low risk of side effects. Two studies did not find an increase in risk of mortality in high-income countries (one study found a different hepatitis B vaccine may be associated with an increase in mortality in low- and middle-income countries). It also found that in a U.S. cohort, those who were vaccinated had lower rates of cancer deaths.

Aside from the health risks of pushing back the first shot, there would also be logistical challenges, experts told STAT. There are no other childhood vaccines recommended at 1 month, and it could be an added burden for pediatricians’ offices to add vaccination appointments and stock the vaccine, said Su Wang, a doctor at Cooperman Barnabas Medical Center in New Jersey and an advisor to the Hepatitis B Foundation.