At their last meeting before the local elections, Environment Canterbury councillors made the symbolic declaration of a nitrate emergency, putting it on the agenda of the next council. But will real action follow?

On Wednesday, at their last meeting before the end of the local elections, Environment Canterbury’s councillors declared a nitrate emergency. The motion was put forward by Vicky Southworth, a councillor who is concluding her term, and asked for the next council to develop “key steps council can take to make more rapid progress on nitrate reduction in groundwater”, including considering “options to reallocate costs via a targeted rate, levy or other mechanism, such that nitrate polluters contribute to the costs of nitrate removal from drinking water”. The motion passed nine votes to seven.

The regional council is responsible for air and water pollution in the Canterbury region, which includes monitoring pollutants in water, and is also responsible for approving RMA applications around land use. Greenpeace has made much of the fact that 15,000 new dairy cows were added to Canterbury’s herd in the first six months of 2025 amid a surge in dairy conversions, approved by ECan.

Nitrate is a widespread groundwater contaminant which comes from cattle urine and synthetic fertiliser, as well as some other sources, and can then trickle into groundwater supplies. Nitrate exposure is associated with bowel cancer risk, even at low levels, and can impact the body’s ability to carry oxygen in the bloodstream, especially in babies. A 2024 report by Earth Sciences New Zealand showed that 12.4% of groundwater sources around the country had exceeded the allowable level of nitrate; the vast majority of those sites were in Canterbury.

Council-owned drinking water supplies must be monitored for nitrates and are almost always below the maximum allowed level. However, in rural areas, many people rely on private bores, drawing on groundwater themselves for their drinking water supplies. Greenpeace has offered a free mail-in water testing service, which it has used to compile a map of nitrate contamination.

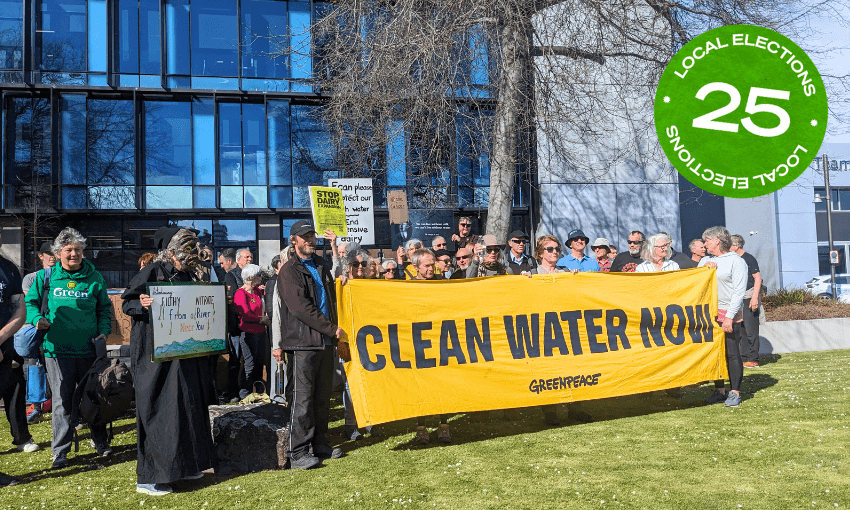

Before the Environment Canterbury meeting began, Greenpeace organised a rally outside the ECan building in central Christchurch, alleging “Environment Canterbury have failed in their duty to protect lakes, rivers and drinking water”. Councillors and council candidates in the upcoming local election were invited to attend, and there was a poster of the nitrate levels around Canterbury.

Will Appelbe, carrying a box of water samples to deliver to ECan (Image: Shanti Mathias)

“It makes me angry that kids in Timaru can’t enjoy the same waterways I did,” said Will Appelbe, a freshwater spokesperson for Greenpeace who spoke at the event. Attendees were invited to bring samples of their own water to the protest, which Appelbe delivered to the council. “This is what corporate dairy pollution has done to Canterbury.” He said that Greenpeace supported the “nitrate emergency” declaration, but said “real action must follow”. Someone in the crowd said the declaration was “10 years too late”.

Kate Gillard, who lives near Oxford, north of Christchurch, said that she had seen nitrate readings increase since moving into her house, which draws on a private well. To her, this was a sign that “somebody is not protecting the water source”. She held a bottle of water from her property, which measured at more than nine milligrams of nitrate per litre. “It’s sick shit,” yelled someone in the crowd. While the Ministry of Health has set a maximum allowable value of 11.3mg of nitrate per litre of water, that limit is based on research around short-term, rather than long-term, exposure, and public health experts have said it should be lowered to 1mg per litre. Gillard said that she and her husband have had to install their own filter so their water is safe.

Kate Gillard hods a sample from her water well, standing in front of a map of nitrates in Canterbury. (Image: Shanti Mathias)

“Declaring an emergency is symbolic,” said Grant Edge, a councillor who is standing again in the North Canterbury/Ōpukepuke constituency and who voted in favour of the motion. Nonetheless, he said an emergency could focus the new council on changing nitrate levels. “I’m hopeful there will be different ways of looking at things, to look at catchments and find bespoke solutions to what is going on.”

Councillor Deon Swiggs, who is standing again in the Christchurch West/Ōpuna constituency, chose to vote against the declaration of emergency. “Emergency declarations are powerful tools that must be used precisely and legally and must come with immediate powers and resources, not symbolic labels during election season,” he wrote on Facebook, saying he would have preferred the wording “drinking water crisis”, which could take into account E. Coli levels in water too. He said that “Canterbury needs evidence-based solutions addressing all contaminants and risks, not selective emergency declarations.”

Craig Pauling says that regional councils have been hamstrung by the government in dealing with freshwater issues (Image: Shanti Mathias)

The drinking water quality is a concern, said Craig Pauling (Ngāi Tahu), Environment Canterbury’s current chair, who is not standing for another term. “It’s been an issue since the early 2000s, when land use began intensifying on the Canterbury Plains,” he said. Declaring an emergency could “bring a bit more urgency to the issue”. Just talking about whether rivers are safe to swim in isn’t enough. “I want to be able to eat out of the river, that’s a higher standard,” said Pauling.

The government has proposed sweeping reforms to freshwater management, and regional councils – which are themselves facing an existential threat – have been unable to make plan changes until a replacement for the RMA comes into force. Otago Regional Council was prevented from passing its freshwater plan by an 11th-hour government intervention in October 2024, and in December, Environment Canterbury voted to pause work on its regional policy statement following a request from the government. “Our hands are tied because of what the government is doing, we’re not allowed to change any of our plans,” Pauling said.

Agriculture minister Todd McClay criticised the declaration as “gimmicky”, saying “we’re all working hard to improve water quality”, while National’s Selwyn MP Nicola Grigg called it a “direct attack on Canterbury farmers”.

Most of Environment Canterbury’s constituents live in Christchurch, and are less affected by drinking water contamination. Despite this, a freshwater scorecard compiled by Greenpeace showed that Environment Canterbury candidates with mostly urban constituents are more supportive of limiting dairy expansion and placing limits on nitrates.

Alison, who attended the Greenpeace demonstration, said that while she lives in the city and isn’t worried about her own drinking water, she saw how much of a problem it was for others. “Canterbury isn’t an ideal place for dairy, with our soil and climate – it’s not surprising there’s a nitrate issue,” she said. She was concerned that the new RMA process and the possibility of removing some regional councils to combine their role with district councils would reduce the ability of people to deal with the issue.

Another protest attendee, Darien, said, “I’m here because they’re just poisoning everyone.”