A Canadian court case has provided insights into the convoluted world of the trans-national rich.

Weihong (Ruby) Liu — who has acknowledged she was a leading member of business organizations in China created by the Communist Party to advance the government’s agenda — now owns three shopping malls and a golf course in B.C.

Often described by Canadian media outlets as a “Vancouver-based billionaire,” Liu has launched contentious court proceedings in Ontario to buy 25 store leases from Canada’s oldest retailer, The Hudson’s Bay Company, which is in bankruptcy protection. Landlords are opposing her bid, in which she says she is prepared to invest $469 million.

Liu has said she moved to Canada more than a decade ago, when she started buying malls in Victoria and Nanaimo, plus the 200-store Tsawwassen Mills, which is on First Nations land.

Two years ago, she led independent videographer Dong Nan, of 56 Below TV, on a tour of her opulent gated estate near UBC.

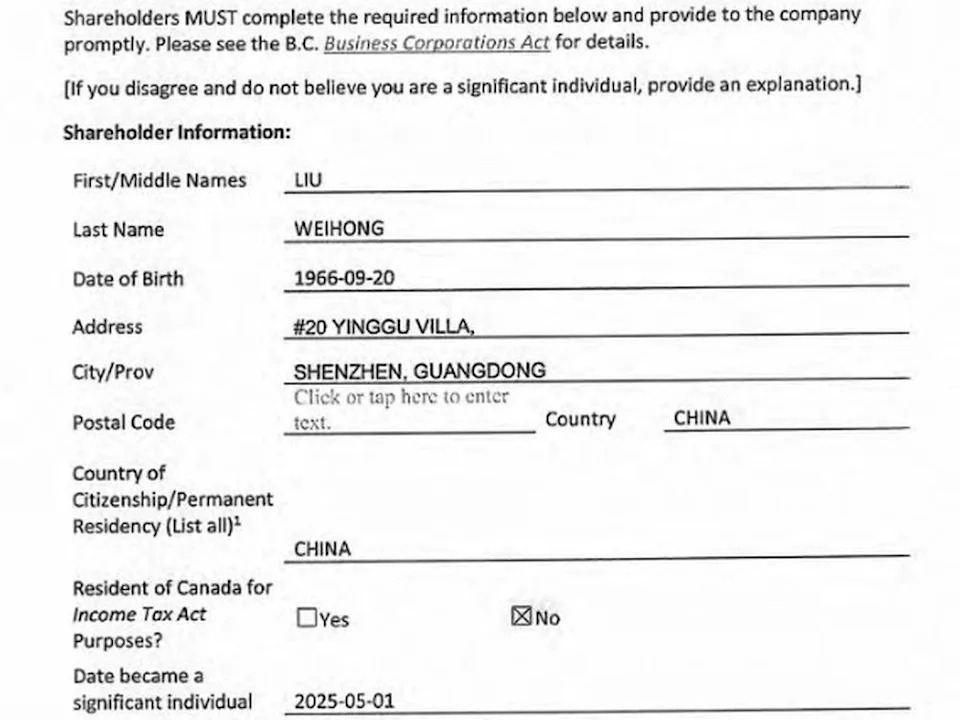

Documents Liu provided last month to the Ontario Superior Court, first brought to light by journalist Bob Mackin, confirm she is not a citizen of Canada.

Instead, when Liu was required under B.C.’s new transparency register to list all of her “countr(ies) of citizenship / permanent residency,” she answered with only one: “China.”

China does not officially allow dual citizenship. Liu once told a Times-Colonist reporter she is a permanent resident of Canada, and her daughter enjoys living here. But the court documents do not mention any immigration status in Canada.

In addition, disregarding her Vancouver mansion, Liu listed her current address as: “20 Yinggu Villa, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China.”

When the transparency document asks if Liu is a “resident of Canada for income tax act purposes,” she ticked off the “No” box.

Without referring to Liu, Postmedia approached immigration specialists and the Canada Revenue Agency to find out how it may be possible for a person with extensive ties to Canada to not be a resident of this country for income tax purposes.

In emails and phone calls this past week, Postmedia tried to reach Liu through her Canadian companies, Central Walk and Tsawwassen Mills. A Central Walk official, Linda Qin, confirmed Thursday she would look into the query. But there had been no reply since.

This fragment of a transparency document recently filed by billionaire Weihong (Ruby) Liu in Ontario Superior Court show her declaring she is not a resident of Canada for tax purposes. She says she is a citizen of China only, listing her only address as in China.

Prominent Vancouver immigration lawyer Richard Kurland, who spoke generally and not about Liu, said the question of whether a permanent resident of Canada can claim they are not a resident for tax purposes has long been controversial.

Kurland, who is author of the Lexbase newsletter and frequently appears before parliamentary committees, said he once, in frustration, asked former Conservative immigration minister Jason Kenney how it’s possible to be a “resident” of Canada to retain one’s immigration status, but not for tax purposes.

Sam Hyman, a retired B.C. immigration lawyer, said that under normal circumstances “the most important factor in determining whether an individual entering Canada becomes resident in Canada for tax purposes” is whether the person “establishes residential ties in Canada.”

Customarily, Hyman said, a person becomes a tax resident of Canada by being present in the country for at least 183 days, or half a year.

“Then a tax resident of Canada is obligated to report their worldwide income and pay tax on it, subject to any applicable agreements or treaties that may pertain,” he said.

The CRA website spells out other factors that require people to acknowledge they are residents of Canada for tax purposes. They include: having business interests in Canada, having dependents in Canada, and having property in Canada, including furniture and automobiles.

The website says the key way to stop being a tax resident of Canada is to “sever all significant residential ties with Canada upon leaving Canada.”

CRA officials offered a different theoretical interpretation of the tax rules when Postmedia asked the hypothetical question: “Is it possible to not be a resident of Canada for tax purposes — even if one lives in Canada, has permanent resident status, and owns hundreds of millions of dollars in commercial and personal real estate in Canada?”

After taking five working days to respond, and emphasizing their answers were general, CRA officials said in an email that each individual’s tax situation is different and “must be gauged accordingly”.

The CRA officials said “an individual who is resident in Canada during a tax year is subject to Canadian income tax on their worldwide income from all sources.”

In contrast, they said, “A non-resident individual is only subject to Canadian income tax on income from sources within Canada.”

The CRA officials then added more layers of complexity to residential tax legislation by saying Canada has tax treaties that can prevent “double taxation”.

“These provisions are known as the ‘tie-breaker rules,’” the officials said. In some cases, they may determine an individual to be a resident of another country and “therefore not deemed to be a resident of Canada.”

Such people are called “deemed non-residents,” said the CRA officials.

“Therefore,” the officials concluded, “the response to your hypothetical question is yes.”

In other words, the officials acknowledged it is possible to live in Canada, have permanent resident status and own hundreds of millions of dollars in commercial and residential property in the country and still “be considered a deemed non-resident under subsection 250(5) of the income tax act.”

Asked if such people could avoid paying income taxes in Canada or, for that matter, in China or another country, the officials said “definitive answers cannot be provided without examining the facts of each case.”

The CRA officials ended by saying that “if Canadians have concerns about potential tax or benefit non-compliance, they can share relevant information with the CRA through the Leads Program,” which is designed to “maintain fairness in the tax system.”

Meanwhile, more than 200 lawyers, business owners and government officials are listed as interested parties in the Ontario Superior Court case, which will determine whether Liu will be allowed to buy 25 store leases from Canada’s ailing Hudson’s Bay Company.

Justice Peter Osborne has reserved his decision in the matter.

Related