With elements of the Tom Phillips case suppressed, what fills the gaps in the public’s understanding? There’s a ready cache of stories New Zealanders tell about themselves that idealise a tough, self-sufficient underdog character.

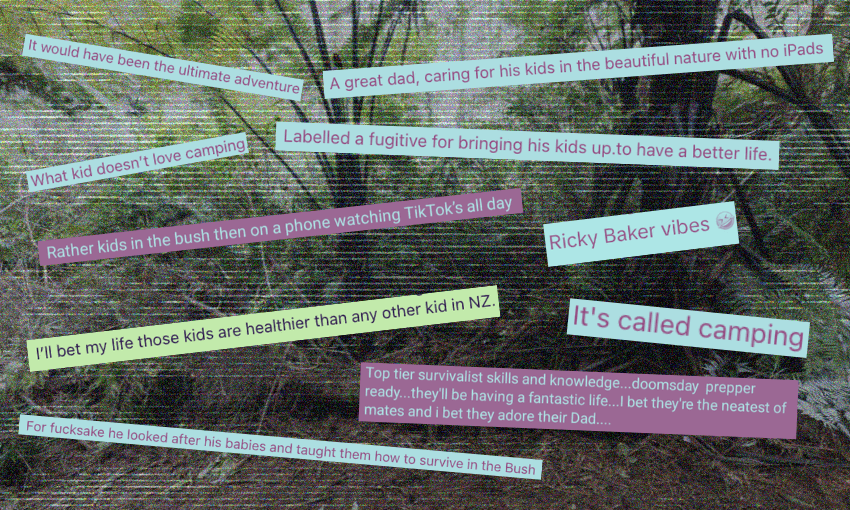

On the internet last week, there was an AI-generated image of a log cabin, or perhaps it was an actual log cabin, somewhere in the world. There was an AI-generated photograph of a happy family, a silhouette of a father with his kids. I won’t repeat the comments because you will have read versions of them everywhere, but suffice to say, the post was glorifying the actions of Tom Phillips, the fugitive who took his children into the dense New Zealand bush, isolating them from friends and family and making them live for four years in his cold and grimy world.

The real Phillips campsite was dirty, makeshift, riddled with evidence of drinking, a miserable shelter in the freezing bush that Stuff reporter Tony Wall described as damp and dismal when he visited. The children are currently in Oranga Tamariki care and will have to be reintegrated into society and reunited with their mother and older siblings, a process experts say will be fraught. Despite this, and the fact he allegedly involved at least one of his children in multiple robberies, many still support Phillips, continuing to insist there are “two sides” to this story, in which he is cast as protagonist.

When news events take place, people make sense from the facts. In the days following Phillips’ shooting, police held multiple news stand-ups, often live-streamed. Along with these updates, journalists sought accounts from those who heard the shooting, questioned authorities about what would happen to the children (who are at the centre of this tragedy), and asked those who live in the Waitomo community about the ending to a story that has been a painful part of their lives since September 2021.

Now, an injunction brought by lawyer Linda Clark on behalf of the Phillips family is in place to prevent the reporting of certain details of the case. There will be several investigations; an IPCA investigation, an internal police inquiry, a coroner’s case, a likely governmental inquiry. Family violence experts are calling for an independent inquiry. Yet, due to the fact this case involves the wellbeing of vulnerable children and their right to privacy, the public may never be allowed the full picture.

So what fills this gap? What conditions exist in our culture for Phillips to be considered, by some, as a decent Kiwi bloke?

Matthew Bannister (Photo: Hayley Theyers)

According to cultural critic Matthew Bannister, who has studied Pākehā masculinities in popular culture, the reaction to the Phillips case cannot be divorced from a pervasive colonial mythology that paints the ideal New Zealander as a kind of “self-sustaining” man alone, conquering the wilderness and defying authority.

“This idea of the masculine Kiwi bloke as tough, self-sufficient, exclusive of women and emotionally inexpressive and also practically accomplished – these are the stories we tell about ourselves. It drives this sense of identity, but in many ways it’s an illusion,” he says.

It is a stereotype that pervades our film and literature. The antihero played by Bruno Lawrence in Smash Palace kidnaps his seven-year-old daughter and rapes his wife; in Sleeping Dogs, the film adaptation of CK Stead’s novel Smith’s Dream, the protagonist, played by Sam Neill, isolates himself following the breakdown of his marriage; in Hunt for the Wilderpeople, based on Barry Crump’s Wild Pork and Watercress, it’s Sam Neill again playing the monosyllabic hunter, on the run with a child in the New Zealand bush.

And on it goes: Bad Blood, Goodbye Pork Pie, and Peter Jackson’s Forgotten Silver all feature some version of this male underdog.

The poster for Smash Palace and scenes from Hunt for the Wilderpeople (top) and Sleeping Dogs (bottom)

While these men do illegal and at times deplorable things, they are still the main characters in these stories; they are humanised, their needs privileged, and a sense of identification with them and understanding of why they would act this way persists, Bannister says.“These are solitary male rebels who disappear off into the bush and then get basically hunted down, and in many cases they are antiheroes. They lose in the end, but New Zealanders identify with these figures quite strongly.”

Last week, family violence expert Carrie Leonetti told The Spinoff’s Alex Casey that myths about masculinity often centre the importance of fathers over mothers, impacting who is believed. “We take men’s suffering and men’s hardship much more seriously than we take women’s suffering and women’s hardship,” she said. “This is a New Zealand problem. This is a culture problem. We have a problem with women, and we have a problem with misogyny.” New Zealand has some of the highest intimate partner violence and child abuse figures in the developing world.

But where did this come from? Bannister says the “undercurrent of maleness” in New Zealand society is borne from colonial times, when white male settlers were trying to establish an identity separate from Britain.

“They had to invent some stuff, so this idea of the ‘Kiwi bloke’ is just a reinvention of working-class masculinity, displaced into a colonial situation. They’re rural, they’re in the bush. There’s this suspicion of institutional authority, they see it as coming from somewhere else, and that’s because they’ve been sold the dream of the colony.”

As the reaction to the Phillips story shows, this dream privileges those who invented it, Bannister says.“I think there would have been a lot more concern, a lot less idealisation of him being the protagonist, as someone who had some inherent right to do what he was doing, if he had been Māori, or a woman. People would not have been so forgiving.

“The way New Zealand is so defensive of this criminal – it speaks to an attitude that tends to normalise white guys as generally doing the right thing and knowing what to do, which is in this case problematic. People flip to this endorsement of masculinity, and all the cultural baggage that New Zealanders have grown up with suggests that women’s perspectives aren’t very important.”

Bannister is a fan of film. He wrote a 2021 book on the works of Taika Waititi, and teaches at Waikato University of Technology’s School of Media Arts. But in this case, where the boundaries between fiction and reality seem more tenuous than ever, he’s troubled. “It’s a very dangerous idea when you let myths rule your life, but it seems people would rather believe these myths than what is occurring, and its effects on all involved. Not just the guy.”