Swimmers take plunge in Chicago River Swim

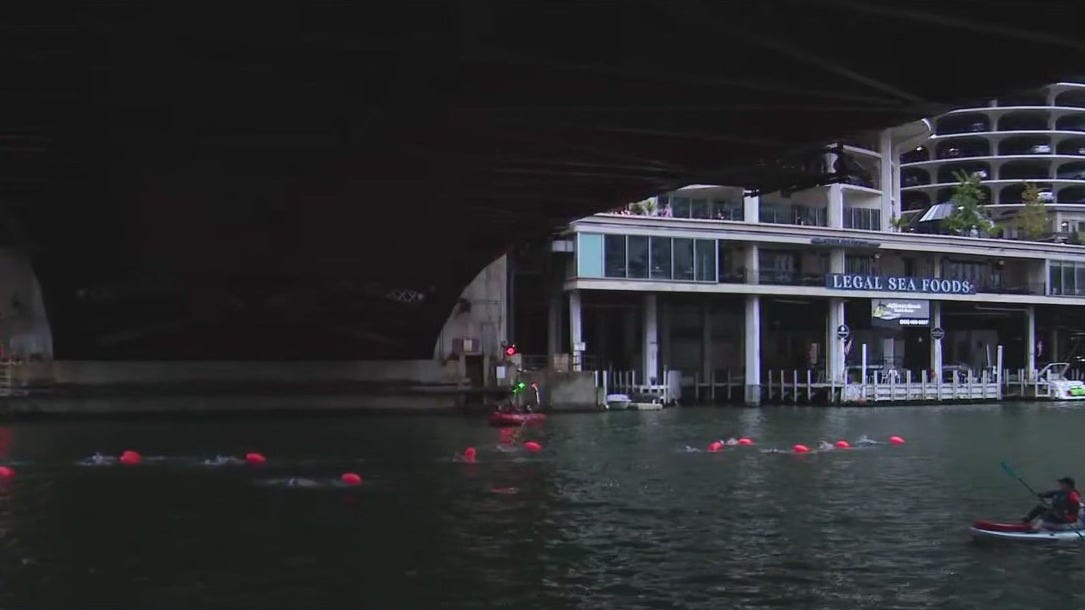

Hundreds of swimmers taking the plunge into the Chicago River for a historic race.

Fox – 32 Chicago

Hundreds of people went against a nearly century-long tide to swim in the Chicago River on Sept. 22.

The event, which was put on for ALS research, marked the first open water swim in the river in 98 years, according to A Long Swim, a nonprofit that organized the event.

More than 260 swimmers participated in two races, including a one-mile and two-mile course, in men’s and women’s divisions. The competition, which was attended by thousands including Mayor Brandon Johnson, raised $150,000 for research for the neurodegenerative condition also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, according to a news release.

The Chicago River, which famously runs through the city’s downtown and is annually dyed green for St. Patrick’s Day, has had a long history of pollution. After decades of cleaning efforts, the river is now considered safe for swimming, according to event organizers.

“The river has been restored as one of our city’s greatest assets. Today shows how far we’ve come in reclaiming our environment for future generations,” Johnson said in opening remarks at the event.

Chicago River Swim raises money for ALS research

The race was organized by A Long Swim, which raises money for ALS research by staging open water swims throughout the United States.

Doug McConnell, a 67-year-old Chicago-area native who lost both his father and sister to the neurodegenerative disease, founded the organization in 2011. To date, the foundation has raised $2.5 million for ALS research.

Prior to the event, McConnell told USA TODAY that the Chicago River Swim was inspired by a similar ALS swim in the canals of Amsterdam that has been running since 2011. He hopes the Chicago swim becomes a similar marquee event.

“Chicago does big events really well, and we just want to be on that list,” McConnell said. “We think it’s a path to a cure for that horrible disease.”

Olympian Olivia Smoliga wins first Chicago River Swim in nearly a century

Olivia Smoliga, a Chicago-area native and Olympic swimmer who earned gold in Rio 2016 and bronze in Tokyo 2020, took first in the women’s one-mile race, finishing the course in just under 23 minutes.

Before the race, Smoliga told USA TODAY that she was unfazed about water quality concerns, but was “a bit nervous” about the length of the swim, as she specializes in 50- to 100-meter races.

“It’s a totally different beast for me,” said Smoliga, who is training to compete in Los Angeles 2028. “It’s going to be crazy on the river, so many people, the views of downtown, I’ll definitely be mentally entertained.”

In the men’s one-mile, Levy Nathan won with a time of 22:22. In the two-mile races, Becca Mann won the women’s heat and Isaac Eilmes took the men’s, both finishing in just over 40 minutes.

Is the Chicago River safe to swim in?

The Chicago River was at one time an open sewer that spread cholera and typhoid in the 19th century, according to event organizers. By 1900, its flow was reversed, allowing the river to clean itself.

In celebration, the Illinois Athletic Association hosted several open water swims. However, by the late 1920s, the river was once again polluted by industrial and human runoff and was deemed unsafe for swimming.

Eventually, restoration efforts began when President Richard Nixon signed the Clean Water Act of 1972, which prevented businesses from dumping in waterways.

Because of advocacy and management efforts over the last five decades, the river’s bacteria levels are now low enough for swimming, event organizers said.

Organizers also monitored whether the water is considered safe based on readings of the concentrations of pollutants, including E. coli and fecal matter.

They conducted testing at eight different points along the race course. As of Sept. 20, all tests came between about 200 and 600 CCE, a measure of bacteria levels.

Below 1,000 CCE is considered safe, 1,000 to 10,000 CCE is considered risky for immunocompromised swimmers, and above 10,000 CCE is considered unsafe.

Melina Khan is a national trending reporter for USA TODAY. She can be reached at melina.khan@usatoday.com.