While Waikato University celebrates, Otago and Auckland continue to argue that the project will be a costly mistake, writes Catherine McGregor in today’s extract from The Bulletin.

To receive The Bulletin in full each weekday, sign up here.

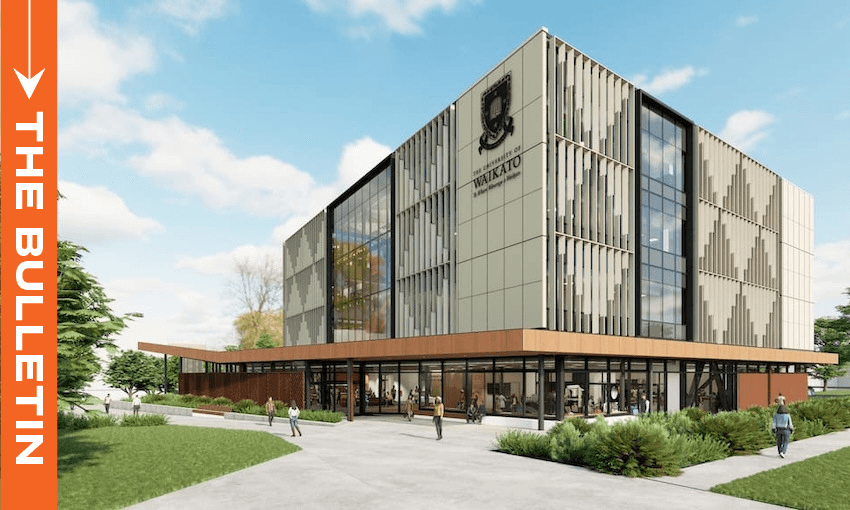

Waikato med school to open in 2028

The government has approved a new graduate-entry medical school at the University of Waikato, set to open in 2028 with 120 places per year. Costing $235 million – $82.85m from the Crown and over $150m from the university and philanthropists – the New Zealand Graduate School of Medicine will focus on primary care and rural health. The project has had a long and bumpy journey. First proposed in 2016, it was shelved by Labour in 2018, revived by National ahead of the 2023 election, and finally approved this week following months of coalition negotiations. Supporters argue the school fills a critical gap in New Zealand’s health workforce. Hauora Taiwhenua, the Rural Health Network, celebrated the announcement, noting that “rural-origin students who train in rural areas and are trained by rural health professionals are six times more likely to work in those rural areas post-graduation”.

Act claims credit for huge savings

While Act initially cast doubt on the school’s cost-effectiveness, the party yesterday claimed a political win, saying its demands helped slash taxpayer contributions from the originally promised $280m to just under $83m. As the Herald’s Thomas Coughlan reports, David Seymour said Act’s “rigorous questioning” led Waikato University to increase its contribution and deliver better value for money. Prime minister Christopher Luxon was more circumspect, attributing the reduced cost to improved economic modelling and reassurances about the amount of philanthropic support available to the project.

Regardless of who deserves the credit, the numbers have shifted dramatically since the election, with the university now on the hook for more than half the total cost. Luxon confirmed that the business case will be publicly released, though Labour and the Greens continue to press for full transparency over the assumptions behind the decision. Both parties have expressed doubt about the plan, with the Greens’ tertiary education spokesman Francisco Hernandez saying the government was planning to “fritter away money on a risky white elephant project”.

Otago and Auckland argue school is unnecessary and costly

Opposition to the Waikato school has been fierce and sustained from the country’s two existing medical schools. While Otago and Auckland will still benefit from 100 extra training places over this government’s term, the universities argue they could expand capacity faster and at lower cost than by building an entirely new school, a view backed by a 2024 PwC report that the universities jointly commissioned They have long maintained that the Waikato proposal is duplicative and expensive, first raising concerns with ministers in 2016 – months before the project was even announced publicly. As John Lewis reports in the ODT, the universities also emphasise their broad existing networks of rural clinical placements and say the major barrier to increasing student training numbers isn’t the number of medical schools, but the provision of placements around the country.

Heavy lobbying by Waikato raised eyebrows

Just as contentious has been the behind-the-scenes lobbying to get the Waikato project across the line. In 2023, RNZ’s Guyon Espiner revealed that Waikato vice-chancellor Neil Quigley, who also chairs the Reserve Bank board, worked closely with National’s Shane Reti on the policy, even referring to the school as a “present” for the party’s second term.

Communications advice was provided by former National minister Steven Joyce, whose firm was paid nearly $1 million by the university over three years. According to documents released under the OIA, Joyce encouraged a shift from quiet lobbying to a public campaign that could, in his words, “shame” the then Labour government into supporting the project. Despite this, Labour never came on board – and now, as the school finally moves forward, questions remain not only about its cost and necessity, but also the integrity of the process that secured its approval.

More reading:

Subscribe to NameEmailSubscribe