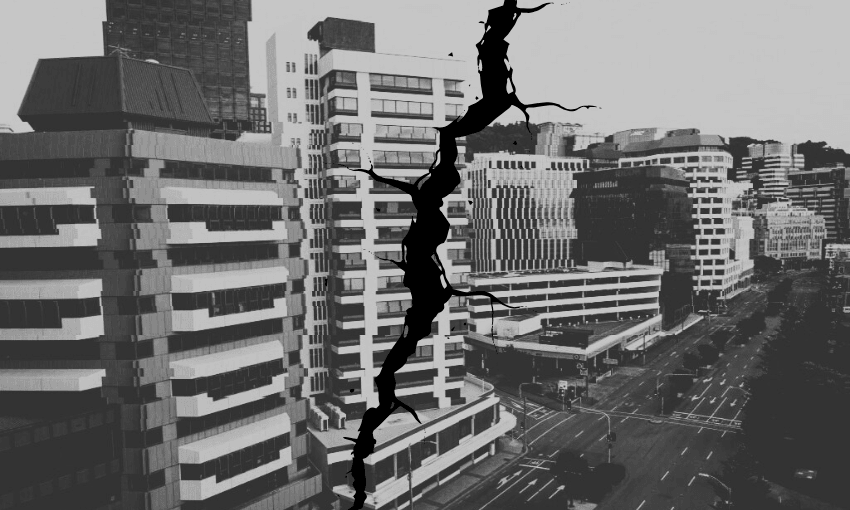

The government’s new earthquake-prone building rules aren’t without risks, but they might finally give Wellington the confidence to grow.

In the early hours of May 25, 1840, a fire tore through 16 flax cottages in the fledgling village of Britannia. Settlers who had arrived only weeks earlier and Māori residents of Pito-One Pā frantically worked together to stem the blaze. Only moments after the fire had subsided, just as everyone had returned to their huts, the ground started moving. A long, severe shaking. Some settlers ran outside, firing pistols, fearing that Māori forces were trying to tear down their homes. Others looked to the skies and speculated that Taranaki Maunga had erupted. It was the first time that most of them had experienced an earthquake.

Five days after the earthquake, the Hutt River burst its banks. That tumultuous week gave force to the argument that they should move the town to the other side of the harbour, where it was later given a new name: Wellington.

Perhaps the settlers should have taken the triple disaster of May 1840 as a sign that Wellington was cursed and never should have been built. But they didn’t, because the natural advantages outweighed the risks. The great harbour of Tara is too large and well located not to have inevitably become the home of a large city. Wellington’s hardly alone in that sense. Many of the world’s great cities are built in high-risk areas. Tokyo and Los Angeles are built on faultlines. Shanghai is in a flood-prone river basin. Mumbai gets monsoons and cyclones. Auckland is built on a bed of volcanoes.

Earthquakes have defined Wellington’s history ever since Europeans started building things out of brick and stone. The city is lucky to have never had a mass-fatality event, but there has been a repeated cycle of damage and despair. When a 7.5-magnitude earthquake hit in 1848, Lieutenant-Governor Edward Eyre melodramatically wrote: “The town of Wellington is in ruins … Terror and dismay reign everywhere.”

The most recent big shake was in 2016, the 7.8-magnitude Kaikōura earthquake. No one in Wellington died (there were two deaths in the South Island), but it did huge damage to the city itself; initial reports found 60 buildings suffered structural damage and 28 were at risk of collapse, most of which had to be demolished.

Wellington has never really bounced back from that damage. Two minutes of shaking turned into a near-decade of slow-rolling destruction caused, ironically, by a law that was meant to keep people safe from earthquakes.

In the wake of the Christchurch earthquake, the National government passed the Building (Earthquake-prone Buildings) Amendment Act. It required building owners to repair buildings within certain deadlines if they were deemed earthquake prone, defined as being 34% or less of the New Building Standard.

The law was well intentioned but had massive flaws. NBS grades could be highly subjective and often not that relevant to actual safety. They were determined based on the worst-performing component in the building, but that wasn’t necessarily reflective of the overall building risk. A bit of loose masonry in a mostly unoccupied area isn’t the same as a critical supporting column in a busy foyer.

There were widespread misunderstandings about what the grade signified, even within the industry. It’s a measure of life safety risk, not building durability. A 100% NBS building may still suffer immense and costly damage in an earthquake, but it’s less likely to kill people. And it’s not a purely linear ranking; the risk scales considerably as the grades get lower.

MBIE staff found the NBS system was not well-understood.

Many of the major buildings Wellington has lost since 2016 weren’t damaged by the earthquake at all; they just received new NBS grades (Wellington Central Library, for example). It was a terrifying existence for many owners. You can insure against your building being destroyed in an earthquake, you can’t insure against some boffin telling you the building you thought was perfectly good was actually a deathtrap that legally required millions of dollars in repairs.

There are countless horror stories of Wellingtonians who bought an apartment in a building that was later assessed as earthquake prone, leaving them with upgrade costs greater than what they originally paid and a home that had lost almost all value. It also wasn’t a particularly good system for ensuring building repairs; Wellington City Council estimated 63% of earthquake-prone buildings in the city were going to miss their remediation deadlines because the owners simply couldn’t afford it.

Many earthquake-prone buildings were unlikely to reach their legally mandated deadlines for repair.

The government’s long-awaited reforms to the earthquake-prone building code, overseen by building and construction minister Chris Penk, were revealed on Monday. Thankfully, it hasn’t become a particularly partisan issue – it helps that National is scrapping policies introduced by National. The opposition broadly agrees that something had to change; it was just a question of how well-executed the change would be.

Penk went big, while staying pragmatic. The most radical option MBIE staff presented to him was a complete removal of earthquake safety requirements, letting the free market decide the level of earthquake risk that building owners and occupiers were willing to bear. Penk didn’t go that far, wisely recognizing it likely would have been too much for the public to accept, but he went further than the second-most radical option he was given.

Under the new system, only two categories of buildings require assessment: unreinforced masonry buildings and concrete buildings taller than three storeys. Everything else gets away scot-free. Every building in Auckland and Northland has been exempted, reflecting the lower seismic risk in those areas.

The new system vastly reduces the number of buildings that will require upgrades or retrofitting: 55% of earthquake-prone buildings (2,900 nationwide) are removed from the list entirely, while most of the remaining buildings will require lesser repairs or will remain on the list but won’t require immediate repairs. Those building owners have been handed a get-out-of-jail-free card. In small towns and rural areas, unreinforced masonry buildings have been given a pass, too; the biggest risk in those instances is the exterior of the building detaching and crushing pedestrians, but that is less likely in less populated areas.

But what about Wellington, the city that became the poster child for this issue? It’s not so simple. Like the rest of the country, about half the buildings currently considered earthquake prone will escape the criteria. But most of the horror-story apartments in Wellington are concrete buildings three storeys or higher, which will still require a full or partial retrofit. There will be no government funding to support them. But the retrofits that are required will be smaller, more targeted and therefore cheaper. Owners will benefit from an extended timeline to complete the works. But for some, an impossibly large bill becoming a bit cheaper will barely move the needle.

The elephant in the room of these reforms is that they will put more lives at risk. The regulatory impact statement makes it clear the changes are “projected to increase the risk to building occupants and pedestrians by 30% compared to the status quo” (though that number is probably overstated, because it assumes that every building under the status quo would have eventually been upgraded, which clearly wasn’t happening).

As we learned in the Covid era, every policy decision carries risks. Experts can recommend the approach with the highest level of public safety, but that usually comes with other downsides. Politicians have to consider the downsides and weigh up how much risk they’re willing to accept.

The old system was too risk-averse. The benefit-cost ratio of the 2013 policy was one of the lowest ever recorded. Even taking into account the benefit of lives saved as a financial formula, it scored a 0.02, meaning that every dollar invested produced two cents of public benefit. And the costs, for Wellington, were existential.

Wellington’s future growth hinges on building apartment buildings in the centre city and around key transport links. But the fears of constantly changing standards and financial Russian roulette every time the building gets an engineer’s assessment scared people off from buying apartments. That made the market less appealing to developers and left the city to stagnate. In a city that has been begging for more construction to spur economic growth and provide much-needed housing, the status quo had clearly become untenable.

These reforms don’t completely end the problem of earthquake-prone buildings in Wellington. They don’t remove the fault line that runs underneath the city. But they provide a level of certainty that Wellington desperately needs. Certainty and stability are the foundation for growth. That foundation may still be prone to shakes, but at least now it’s base-isolated.