I knew something was seriously amiss the day a pair of grim-faced MI5 spooks marched into my office, shut the door and told me to sit down.

‘I’m David,’ said one, ‘and this is Sue.’ My first thought was what average names for spies. My second was: they’re not their real names.

I’d been given a two-minute heads up they were on their way. I was Secretary of State at the time in the Department of Digital Culture, Media and Sport and had a busy diary. ‘I can’t see them now,’ I said to a member of my private office staff who’d rushed into my office to warn me.

‘I’m afraid you don’t have a choice,’ she said.

As a Cabinet Minister with responsibility for digital and telecommunications, I was not unfamiliar with the world of spies.

I was frequently called into the lead-lined departmental STRAP room – STRAP being the codeword for a system that protects highly sensitive intelligence – where I received Rosa briefings.

These involved vital information – held on a separate data system – printed on pink paper. Once briefed and the papers read, I would hand them back and give my opinion or instructions. Even more secure meetings – perhaps when we had to link into someone in another country – were held in the COBR rooms in Whitehall.

I can never reveal what any of those meetings were about but what I can say is that I learned how effectively China had penetrated our communications network and how Russia, operating on a different level, also presented a grave threat to our national security.

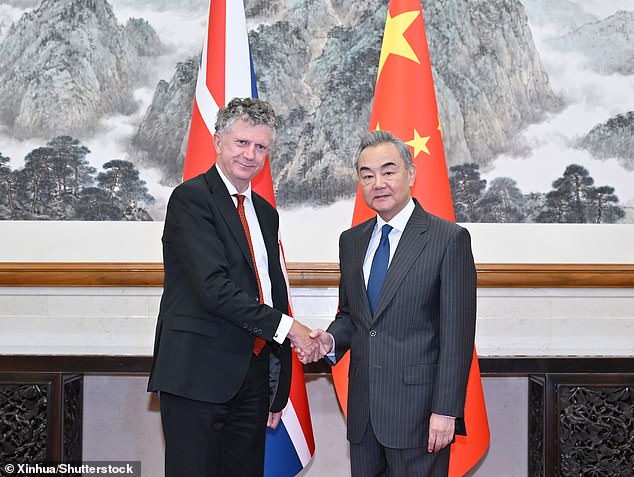

The Prime Minister’s national security adviser, Jonathan Powell, with Wang Yi, China’s minister of foreign affairs, met for talks in Beijing in July

I came to understand that everything from our mobile phone networks and the microchips that run our fridges can be compromised, and how frequently corporations and organisations are held to ransom by cyber-attacks, most of which the public never get to hear about.

Had there been a damaging departmental leak? Was I in some way responsible? What they went on to say – again, I cannot disclose what MI5 told me – shocked me to the core.

And as the latest ‘spy’ crisis convulses Westminster – the eleventh-hour collapse of the court case against a parliamentary researcher and an academic accused of spying for China (which they deny) – I’ve been reminded of that incident again.

The focus is now on the alleged influence exerted by Starmer’s national security adviser, Jonathan Powell. He may or may not be implicated – the Government denied he played any part in the ‘substance or the evidence’ – but in my view that’s ignoring the real problem here.

Let me explain: Westminster is overflowing with ambitious young researchers and aides. They are desperate to boost their career prospects by working for MPs, but are poorly paid and struggling with the expense of living in the capital.

So, when they receive an email from an organisation purporting to be a London-based research firm asking if they would write a 5,000-word report on, say, NHS failings for one of their clients with a fee of £5,000 proposed, many take the bait.

The organisation appears to be British, its website is impressive, and over a fine lunch the young researcher is told about a European client about to do business in the UK who wants a better understanding of how the country works. He/she is the perfect person to help!

Two weeks after the report is received, another email arrives telling them the client was so impressed they want to commission another – this time on how the British state education system achieves meritocracy across social divides. The fee is now £10,000 – AND the client would like to meet them in Paris! First-class travel and a five-star hotel and would they like to bring their partner, too?

The impecunious young researcher accepts. Of course they do. It all seems innocent enough and a relationship is building. They are wined and dined and flattered, and they become friends with the ‘firm’s’ representatives. They share life stories and secrets. More reports are commissioned, more money, more fabulous dinners and evenings out – until the crunch.

Suddenly, they are asked to draft some parliamentary questions which are favourable to . . . China – and persuade their MP to ask them in the Commons. Or perhaps they are asked to leak information from the MP’s office to what we now know is the ‘handler’. The researcher at last smells a rat, tries to back out, but it’s too late. And that’s when the blackmail begins.

This is a scenario played out in Westminster for decades. Keir Starmer knows it, Jonathan Powell knows it, as do the Commons authorities. Yet researchers are still being ensnared on a daily basis. How? Because no training whatsoever is given to MPs or to their junior staff on protecting themselves.

Yes, a dedicated training unit and programme, written and delivered by MI5, to educate those who work in the House of Commons on the importance of national security, the duplicitous ways and means of foreign actors and digital safety would cost money. But can we really risk NOT providing this any longer? Recent events suggest not.