They erected safari-style tents for shade and strung hammocks between poles. Supplies were scheduled to arrive every three or four days. They set up a generator to cook meals and power their equipment and hired a crew of locals to help keep everything running smoothly.

When the experiment began, the team spent the day positioning the electrodes on the bats they planned to study that night. They drank coffee in the evening and waited for midnight. By 1 a.m., they were ready to release the first bat for its hour of flying. Then another, and another, until four had been sent into the night sky and retrieved, and by then the morning sun was showing on the horizon.

If the night’s work was a success, the team poured celebratory glasses of amarula, a cream liqueur from South Africa, before going to bed for a few hours of sleep.

The team had anticipated many problems—they covered their electronics with parafilm as protection from sea spray, for example—but still hiccups arose.

The adapters they had brought from Israel would not work with the available oxygen tanks, and they had to commission a shop in Tanzania to manufacture new ones. They were dependent on a contact in Tanzania to send over anything they suddenly needed—including a pair of eyeglasses and a new phone to replace the one Ulanovsky ruined in the ocean.

“It was constant problem-solving all the time,” Ulanovsky says. To pull off a study of this magnitude, he learned, “you always have to be on the alert.”

T

he time on the island, with the disruptions and “not knowing whether the experiments are going to work or not,” was enough to make Ulanovsky anxious. But he had been thinking about studying bats in the wild for almost two decades, and he had to believe this would be worth it.

When the weather turned, they packed up and went back to his lab. They had split the recordings across three different brain areas, and they worried they might not have enough data to draw reliable conclusions about any one area. That turned out to be the case, so they returned to Latham Island for another three weeks in February 2024 and got what they needed.

They first analyzed the presubiculum. There, about 25 percent of the neurons had head-direction tuning, they found, firing in response to a specific head orientation—a proportion similar to that seen in lab studies, which confirmed that some features exist in both the lab and the wild. Neuroscientists had suspected that head direction cells could serve as a neural compass, but some findings had shown that the tuning of the cells could change with spatial cues, which would make them unreliable for navigating in the wild.

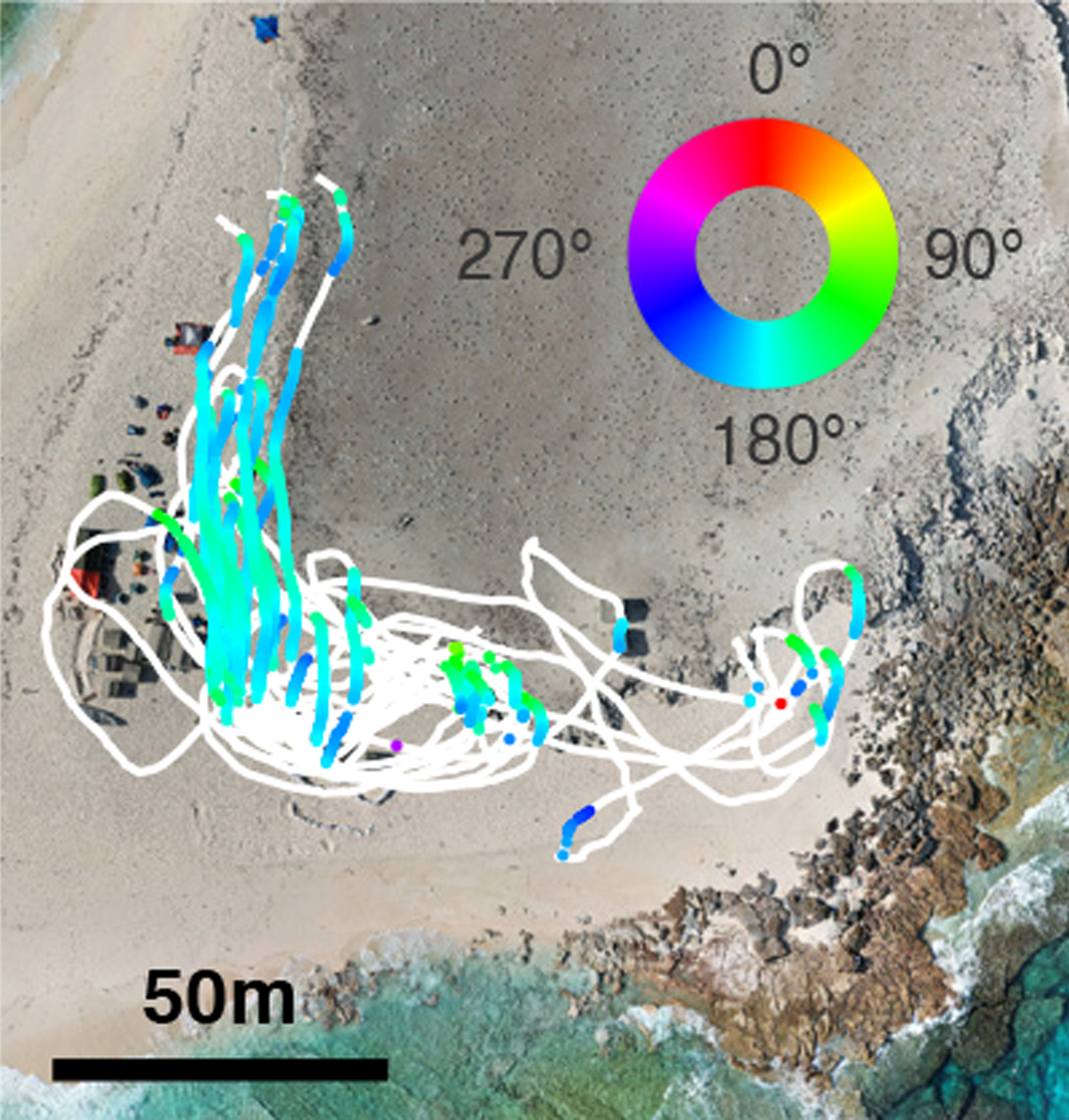

Preferred perspective: Head direction cells are tuned to specific orientations, such as this cell that mostly fires (colored dots) when the bat is facing south while it explores the island (white line).

But the study backed up the compass idea: Head direction cells fired to the same head orientation no matter where the bat was on the island, showing that the tuning was global over large areas. Because the tuning remained stable before and after moonrise and with or without cloud cover, it showed the cells were immune to celestial cues and therefore could be a reliable compass.

Because the bats were not native to the island, the experiment also shed light on how those maps form. On the first couple of nights, neurons seemed lost, firing no matter the bat’s orientation. But as the nights passed, the neurons responded more consistently to just one orientation, indicating that their direction maps became stabilized with learning. The team is currently analyzing the data from the two remaining areas.

The Latham Island project did not come cheap—it required funding from the European Research Council, the Israel Science Foundation and the Weizmann Institute, among other funders. But Ulanovsky’s new findings have uncovered important features of navigation, says Couzin, and the naturalistic approach opens up “potential opportunities to really reveal why the brain is structured in the way it’s structured.”

Ulanovsky is far from the only neuroscientist thinking about the natural behavior of animals. But neuroethology was previously seen as “old-fashioned, kind of something from the ’60s,” and it was Ulanovsky who helped bring it “into modern times,” Moss says.

Ulanovsky consolidated his thoughts in his recent book, “Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors.” Warrant says it is already an important contribution, encouraging neuroscientists to think outside the box while providing practical ways to do it, but Ulanovsky is not inflexible about natural studies. “It looks like I’m preaching that everybody should go outside,” he says, but that is not the case. He still sees the importance of more controlled studies and says that “people who do even a little step towards a more naturalistic experiment, even in the confines of the lab, will find very interesting things.”

Ulanovsky has added a maze inside the tunnel at Weizmann to study how bats work in truly complex environments. But he plans to go back to the island in 2026 to study pairs or groups of bats. “As you can imagine, to do the kinds of things that we are doing—build those tunnels, go study bats on islands—you have to be an optimist but also a realist,” he says. “You cannot be just a dreamer. Dreams are not enough.”