Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Cyber Security myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

South Korea has prohibited its citizens from travelling to parts of Cambodia following a surge of kidnappings tied to industrial-scale cyber-scam centres in the south-east Asian country.

Seoul has received reports of the abduction or forcible confinement by criminal gangs of 330 South Korean nationals in the first eight months of this year. Many have been forced to work in prison-like complexes running online scams targeting people around the world.

The travel ban, which came into force this week, applies to several areas including Bokor Mountain in Cambodia’s Kampot Province, where the body of a South Korean student was discovered in August having allegedly been held captive and tortured by a local crime group.

South Korea’s national security adviser Wi Sung-lac told a press briefing this week that “the online scam industry in Cambodia is reportedly employing around 200,000 people of various nationalities . . . while the exact number of Koreans involved there is unclear, our related authorities estimate it to be around 1,000 individuals”.

Wi added that, while many of the South Korean nationals working at the Cambodian cyber-scam compounds had been abducted or lured to the country with false promises of legitimate job offers, “some people who went to Cambodia voluntarily became involved in criminal activity, and later wanted to return, but they couldn’t”.

“In a sense, they are both victims and offenders at the same time,” Wi said.

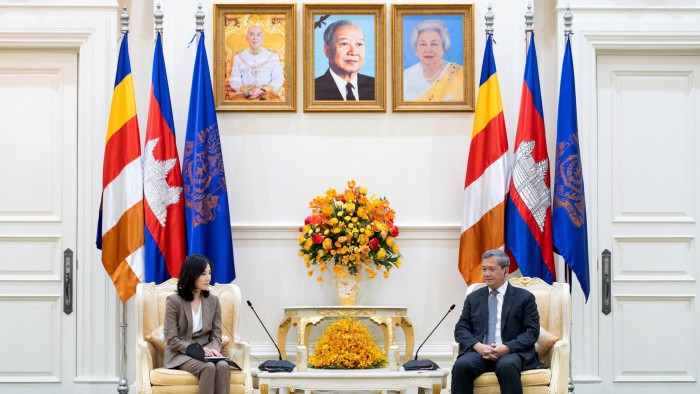

Seoul has dispatched an inter-agency delegation to Phnom Penh in response to the mounting diplomatic crisis.

On Thursday, South Korea’s foreign ministry said that Cambodia’s prime minister Hun Manet had “expressed his deep regret and sorrow” over the death of the South Korean student, and “stated that he would make even greater efforts to arrest the suspects currently at large and to protect South Korean nationals in Cambodia”.

Operations conducted by the cyber-scam centres, which are assisted by artificial intelligence tools such as face-swapping and chatbots, include so-called “pig-butchering scams”, where fraudsters gain the trust of victims often through the fictitious promise of a romantic relationship. The victims then invest in fraudulent schemes or assets such as fake cryptocurrency projects.

The US government estimates that Americans lost at least $10bn to south-east Asia-based scam operations in 2024, a 66 per cent increase on the previous year.

UN experts this year warned of a “humanitarian and human rights crisis” over “large-scale trafficking in persons for purposes of forced labour and forced criminality in scam compounds across south-east Asia”.

Citing a proliferation of such facilities since the coronavirus pandemic in Myanmar, Laos, the Philippines and Malaysia as well as in Cambodia, the experts said that “once trafficked, victims are deprived of their liberty and subjected to torture, ill treatment, severe violence and abuse including beatings, electrocution, solitary confinement and sexual violence”.

On Wednesday, the UK and US governments announced they were imposing sanctions on the Prince Group, a Cambodian network accused of running criminal cyber-scam facilities.

The sanctions included an asset freeze on London properties with an estimated value of £130mn — among them an office building in the City of London and a residential property in St John’s Wood belonging to Prince Group chair Chen Zhi, a citizen of Cambodia, Cyprus and Vanuatu.

According to the US Treasury, Chen is a “38-year-old Chinese émigré who has since renounced his Chinese citizenship and has built a business empire in Cambodia through the Prince Group”.

It noted the group’s “burgeoning operations” in the Micronesian country of Palau, which it said was being targeted by “predatory investments by transnational organized criminal groups originating from the People’s Republic of China”.

Amnesty International said in a June report that its findings “suggest there has been co-ordination and possibly collusion between Chinese compound bosses and the Cambodian police, who have failed to shut down compounds despite the slew of human rights abuses taking place inside”.