SPRINGFIELD — With the clock ticking down to avert an impending public transit fiscal cliff, Illinois Democrats in the pre-dawn hours Friday muscled through a $1.5 billion plan that diverts state gas tax and road fund revenue for mass transit, likely raises the sales tax in the Chicago region and significantly hikes fares on the Illinois Tollway.

The measure, which supporters called historic, overhauls the Chicago region’s mass transit system by creating a new governing body to oversee the Chicago Transit Authority, Metra and Pace.

But while the last-minute legislation was lauded for not including the broad taxes that tanked previous versions, its redirection of funds now used statewide for road construction was summarily slammed by incensed downstate Republicans who argued they and their constituents were getting the short end of the bargain.

Just after 4:15 a.m. Friday, the Senate approved the bill 36-21 with nearly all Democrats voting in favor. That was about three hours after House Democrats OK’d the legislation with 72 votes to the GOP’s 32. Democrats hold supermajorities in both chambers, and the bill now heads to Gov. JB Pritzker’s desk.

The votes came after years of work and months of wrangling among Democrats, including just earlier this week when a previous proposal from House Democrats was shot down by Pritzker, a fellow Democrat.

The new proposal cobbled together a few new ideas with some old ones to raise the roughly $1.5 billion, which advocates and some lawmakers say is necessary for the region’s transit system to work adequately.

The largest chunks come from diverting $860 million in state tax revenue on motor fuel sales and $200 million from the interest earned on the state’s road fund for mass transit uses. That money typically goes toward road construction projects. An additional $400 million would come from authorizing an increase of 0.25 percentage points to the sales tax issued by the Regional Transportation Authority for Chicago’s six-county area.

As a counterbalance to pulling hundreds of millions of dollars in funding for road work, the bill also included a sharp, 45-cent-per-toll increase on the Illinois Tollway, which one GOP lawmaker said amounted to a 60% increase. The new tollway fares could generate as much as $1 billion annually for roadwork on the tollways that serve about a dozen counties, supporters said.

Together, that amounted to “a way that we can avoid raising significant taxes on folks but still be able to do a transformational investment in transit,” said Democratic state Rep. Eva-Dina Delgado of Chicago, a key transit negotiator in the House.

“This bill is the culmination of about five years’ worth of work. There is an urgent need for us to make a plan for what’s going to happen, the transit system in northeastern Illinois in particular,” she said during a floor debate. “Now, while this is an issue that’s happening across the state, we know that without action now, there could be pink slips issued to folks. There could be a 40% service cut. And we just can’t wait to be able to resolve that issue.”

Aside from the Democrats’ call for sweeping changes to Chicago-area transit, another key negotiator on the issue described the effort as the most ambitious of any state.

“This isn’t just another transportation bill. It’s a transformation bill. For 50 years, Illinois has been trying to fix transit one piece at a time,” said state Rep. Kam Buckner, a Chicago Democrat. “No other state has ever attempted a reform this large. No other state has had the courage to say, ‘We’re going to fix this and not just patch it anymore.’ This bill creates a unified system that will replace fragmentation with coordination.”

But Republicans, particularly those from downstate districts, argued the plan would divert more than $400 million a year — money largely intended for road projects — to assist Chicago-area transit needs, while leaving downstate regions with less than half that amount in return for their transit needs.

“I appreciate this is five years of culmination of hard work for you. It’s six years of culmination of betrayal for me,” state Rep. Ryan Spain of Peoria said.

Democratic state Sen. Patrick Joyce, one of two Democrats to vote against the measure, said he did so because of “downstate concerns” related to the road fund diversions.

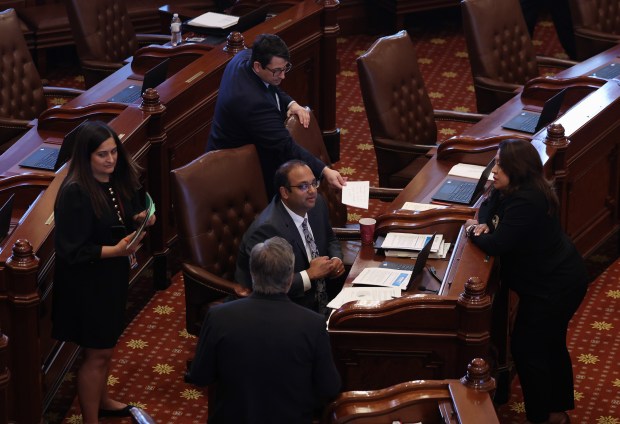

The top Senate negotiator, Democratic state Sen. Ram Villivalam of Chicago, disputed a GOP analysis showing large net losses, though Villivalam did not provide his own estimates on the matter.

State Sen. Ram Villivalam, center, is surrounded by Senate colleagues at the Illinois Capitol during the legislative session, Oct. 30, 2025, in Springfield. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

State Sen. Ram Villivalam, center, is surrounded by Senate colleagues at the Illinois Capitol during the legislative session, Oct. 30, 2025, in Springfield. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

State Sen. Seth Lewis, the only Republican to vote in favor of the transit bill in his chamber, said he thought the revenue generation in the latest legislation was fairer than new taxes, including the $1.50 fee on deliveries and real estate transfer tax that were part of the bill that passed the Senate in May before dying in the House.

“We still needed to find revenue to fix transit,” Lewis of northwest suburban Bartlett said early Friday. “And what was presented today I thought was the most fair. It helps to preserve jobs. It helps to create jobs. It helps to invest in capital.”

The proposal, which would go into effect June 1, was the General Assembly’s second attempt at a transit funding bill this week, after Pritzker shot down the House Democrats’ earlier proposal that included taxes on streaming services and billionaires, fees on concerts and revenue from allowing new speed cameras to be installed in Chicago suburbs.

The governor’s quick rejection prompted the House Democrats to devise the latest set of revenue options, months after they didn’t vote on the bill Senate Democrats passed in the spring.

Lawmakers scrambled on the final night of the fall legislative session and the last scheduled meeting of the year for the full House and Senate.

During a committee hearing Thursday evening, before new language had been publicly introduced, the proposed measure faced pushback from lawmakers who suggested it would fund Chicago-area transit at the expense of downstate infrastructure. Opponents also expressed frustration that they were asked to debate the proposal without a version of the bill ready to read.

In addition to the 45-cent-per-toll hike for passenger vehicles on Illinois State Toll Highway Authority roads, the legislation called for increasing tolls for commercial vehicles by 30%. Tolls could continue to increase in subsequent years through inflation-based increases, according to the bill.

The revenue from the toll hike would generate between $750 million and $1 billion annually and would be put back into the tollway and not used directly for mass transit, supporters said.

The move was intended to offset the money diverted from highway projects and appeared to have won the blessing of the politically influential International Union of Operating Engineers Local 150, which opposed a failed springtime effort to raise tolls.

Downstaters, including Spain, questioned the decision to divert revenue to transit in the Chicago region rather than to a fund that would likely have been used to improve downstate roads.

Interest from the state’s road fund would be diverted for public transit, with 10 percent of that funding being sent downstate while the rest was dedicated for the Chicago area, Delgado told lawmakers.

Additionally, the changes would divert gas tax money from state construction and road funds – where it generally goes now – to transit. Under the new bill, the motor fuel tax would go to a Chicago-area dedicated public transit fund and a corresponding downstate fund, with an 85-15 split in favor of the Chicago area.

Downstate systems would get just under $150 million from the main funding mechanisms, Delgado said. But Republicans said that added up to far from a worthwhile tradeoff, given the amount they expected to lose due to diversions from road infrastructure projects to mass transit under the bill.

Democratic state Rep. Ann Williams of Chicago, chair of the committee that discussed the bill, acknowledged that the state road fund is primarily spent on roads, but said its current definition also allows it to be used for mass transit.

Republicans said uniformly during the House floor debate that the bill didn’t need to be passed in the wee hours of Halloween, given the fiscal cliff wasn’t set to arrive until sometime next year and the regional budget deficit had recently been revised down.

“We are never going to collaborate and work on a deal if you continue to screw us over, to screw each other over, and not have any respect for the deal,” House Republican Leader Tony McCombie of Savanna said.

Legislators hoped the new proposal would help prevent the CTA, Metra and Pace from cutting jobs and making drastic service cuts as hundreds of millions of dollars in federal pandemic aid runs out.

The CTA, in particular, warned it was facing the “single-largest transit service cut in the modern history of the Chicago Transit Authority,” as the crisis was described by acting agency president Nora Leerhsen earlier this month.

Without more money, the CTA warned, it would have to cut transit service by as much as 25% starting next August.

Regional Transportation Authority board Chairman Kirk Dillard, center, talks with a colleague outside Senate hearing rooms during the legislative session at the Illinois Capitol, Oct. 30, 2025, in Springfield. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

Regional Transportation Authority board Chairman Kirk Dillard, center, talks with a colleague outside Senate hearing rooms during the legislative session at the Illinois Capitol, Oct. 30, 2025, in Springfield. (John J. Kim/Chicago Tribune)

The RTA, which oversees the CTA along with sister agencies Metra and Pace, had long warned that the looming structural fiscal deficit would devastate mass transit in the Chicago region if lawmakers in Springfield didn’t raise more money.

If legislation doesn’t become law, the CTA is expected to hit the fiscal cliff — which is caused by the depletion of federal pandemic aid and ridership numbers that simply haven’t recovered to pre-pandemic levels — before Metra and Pace. Neither of the latter two agencies was expected to cut bus or train service next year, but both warned they would have to make cuts in 2027 and beyond without more state funding.

For months, the RTA said the budget gap next year would total around $770 million. But less than two weeks before the start of the veto session, the agency sharply revised that projection downward, attributing the change mostly to an expansion of the state sales tax.

Now, the RTA says, the regional budget deficit next year is about $230 million, although it will balloon to more than $800 million in 2027 and beyond.

The proposed spending beyond the more immediate cliff further angered Republicans.

“Spending more money than we need to at the current time is not the right answer,” state Rep. Dan Ugaste of Geneva said in the House floor debate that stretched past 2 a.m. Friday.

Beyond the funding cliff, the bill also addressed what lawmakers have said are much-needed structural changes for the transit systems — most notably by replacing the RTA with a new entity called the Northern Illinois Transit Authority, which would centralize fare-setting, service standards and an infrastructure plan across the three transit agencies.

Currently, each system is largely governed by its own board, with some oversight from RTA.

The NITA board would have 20 members – five each from the city of Chicago, suburban Cook County, the collar counties and the governor. The CTA, Metra and Pace would continue to have “service” boards reporting to NITA.

The CTA board would have seven members, while Metra and Pace would each have 11. The service boards would be charged with developing budgets and other financial plans and sharing them with the NITA Board.

The Chicago transit region must come up with strategies to address public safety concerns along public bus and train lines. This entails the creation of a law enforcement task force led by the Cook County Sheriff’s Department in coordination with Chicago police, Metra police, Illinois State Police and various suburban police departments.

The bill also creates a transit ambassador program to assist riders with other issues while using the transit system.

On the House floor, Democratic state Rep. Matt Hanson acknowledged the bill wasn’t perfect but said it’s “a great start” and “it’s what Chicago and Illinois deserves.”

“It’s going to be on all of us and our successors to make sure that we get this right in follow-up legislation,” said the Democrat from far west suburban Montgomery who is also a train engineer, “to make sure we get this right and that the accountability standards that are finally going to be in place for all these agencies are adhered to, to make sure that we continue to invest properly.”

Villivalam, the Senate sponsor, said the measure represented a consensus after hours of testimony.

“So no, we’re not going to let this moment pass,” he said. “We are moving forward.”