“The drone struck down the hostel right next to ours. It completely shattered that building and our building was also damaged.”

Months later, when she found out she had been working in a drone factory, she thought back to the attack and realised that was why they had been targeted.

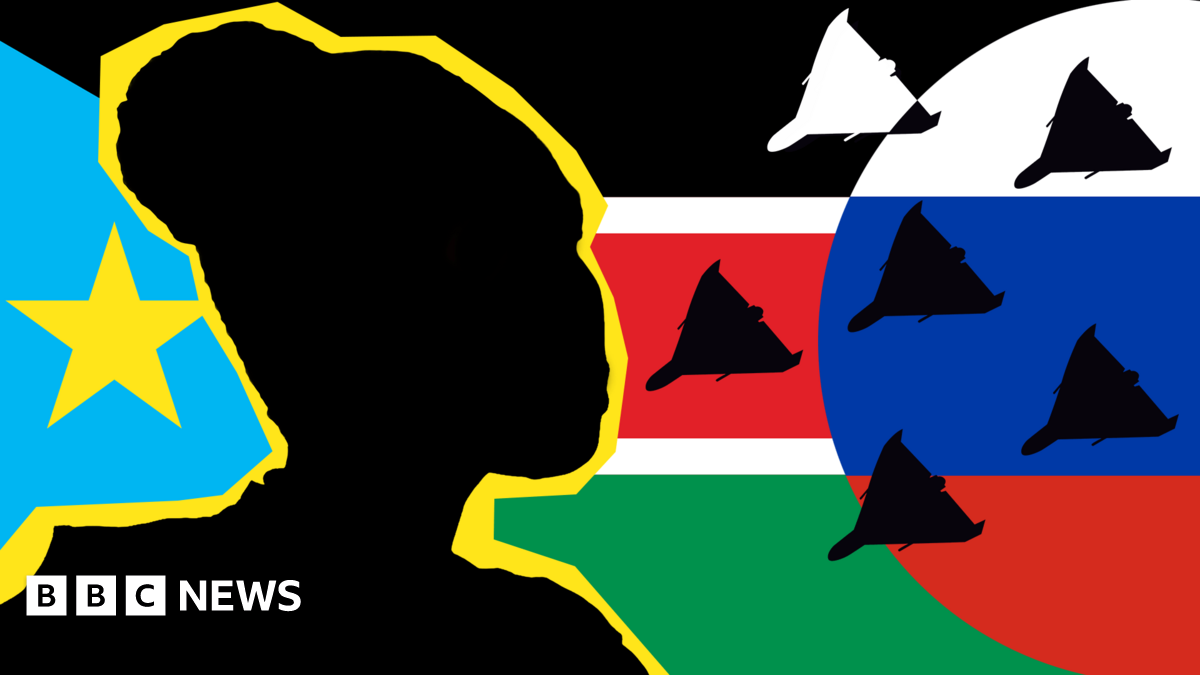

“Ukraine knew that the African girls who had come to work in the drone factories, lived in that hostel that was struck down. It was in the news. When Ukraine was accused of hitting civilian houses, they said: ‘No, those are workers working in drone factories.'”

A few women left without notifying the programme after the drone attack, prompting the organisers to seize the workers’ passports for a while.

When asked why the hostel attack and existing reports about Alabuga being at the centre of Russia’s drone production had not raised her suspicions, Adau said she had been repeatedly assured by staff that recruits would only work in the fields they had signed up for.

“The allegations that we would be building drones felt to me like anti-Russian propaganda,” she explained.

“There is a lot of fake news when it comes to Russia, trying to make Russia look bad. The Special Economic Zone used to have people working there from Europe and America, but they all left after the Ukraine-Russia war because of the sanctions on Russia. So when Russia started looking for Africans to work there, it felt like they were just trying to fill up the spots the Europeans left.”

After Adau handed in her notice, her family sent her a ticket home, but she says many women cannot afford to pay for a return flight and end up stuck there – particularly because their pay is much lower than advertised. Adau was meant to earn $600 (£450) per month, but only got a sixth of that.

“They deducted money for our rent, for our Russian classes, for the Wi-Fi, for our transport to work, for taxes. And then they also said that if we skipped a day of work, they’d deduct $50. If we set off the fire alarm whilst cooking, they’d deduct $60. If we didn’t hand in our Russian language homework, or if we skipped class, they’d deduct from your salary.”

The Alabuga Start programme told the BBC that salaries partly depended on performance and behaviour in the workplace.

We spoke to another woman on the programme who did not want to be named for fear of reprisals on social media. She says she had a more positive experience at Alabuga.

“To be honest every company has rules. How can they pay you your full salary if you miss work, or don’t perform well? Everything is logical, no-one is subjected to what they do not want. Most of the girls who end up leaving missed work and didn’t follow the rules. Alabuga doesn’t hold anyone hostage, you can leave at any time,” the unnamed woman told the BBC.

But Adau says working for Russia’s war machine was devastating.

“It felt terrible. There was a time when I got back to my hostel and I cried. I thought to myself: ‘I can’t believe this is what I’m doing now.’ It felt horrible having a hand in constructing something that is taking so many lives.”