In recent months, 2026 men’s World Cup host cities in the United States have watched on as President Donald Trump has repeatedly warned that he is prepared to relocate matches from cities he deems to be unsafe.

While FIFA’s contracts are with the host cities directly, rather than the U.S. government, the World Cup organizer suggested it would fall into line with President Trump when a spokesperson said in October: “Safety and security are obviously the government’s responsibility and they decide what is in the best interest for public safety.”

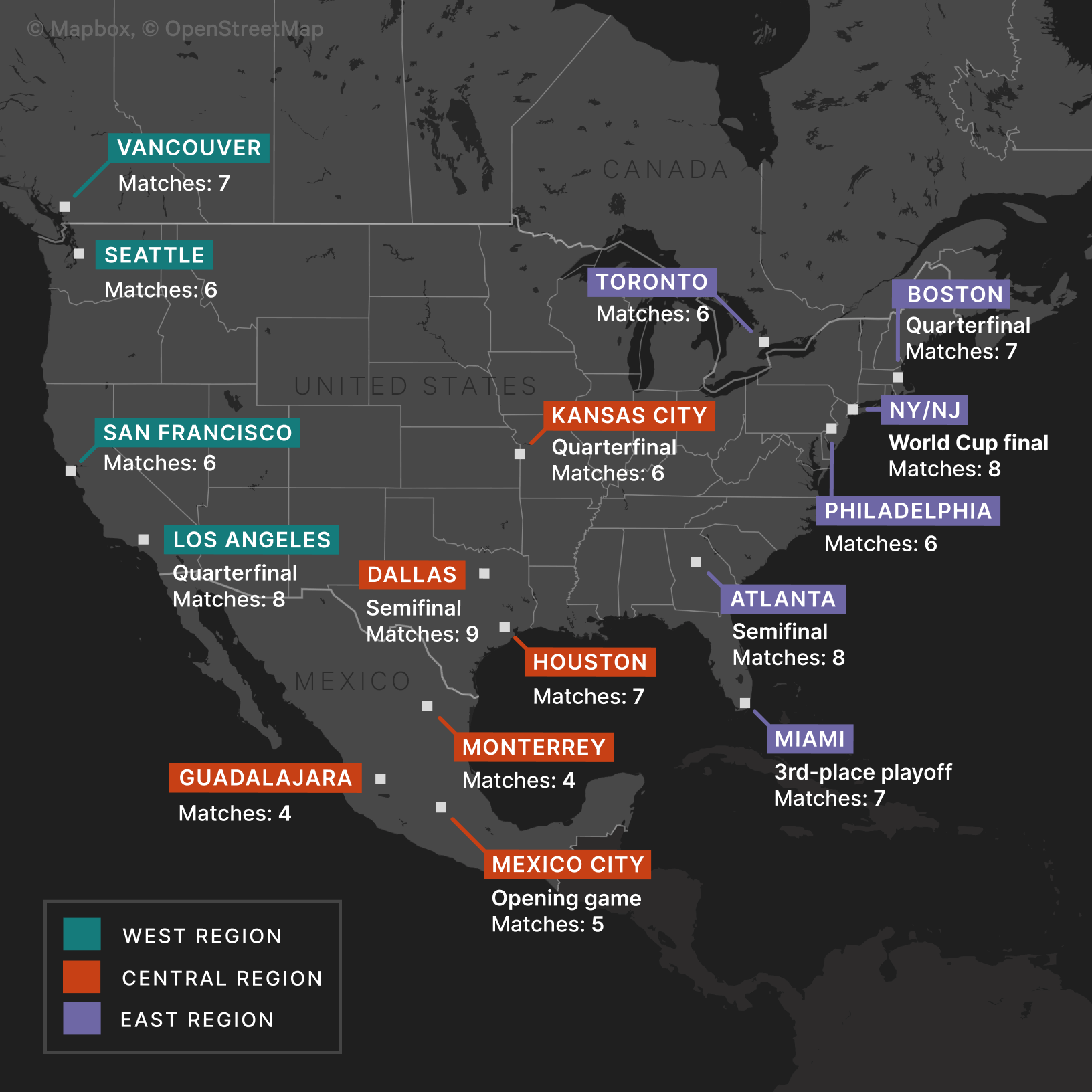

President Trump has name-checked Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Boston as areas of concern during his presidency, all of which are due to be World Cup cities, even if the games themselves are in the broader surrounding areas.

He said in late September: “If somebody is doing a bad job, and if I feel there are unsafe conditions, I would call Gianni (Infantino), the head of FIFA, who’s phenomenal, and I would say, ‘Let’s move it to another location.’ And he would do that. He wouldn’t love to do it, but he’d do it very easily.”

One challenge this has posed for host cities relates to their attempts to drive local sponsorship for the tournament. While FIFA has exclusivity for its own sponsors at stadium venues, the host cities are able to seek revenue around fan festivals in non-competing categories. However, several host city executives, speaking anonymously to The Athletic when discussing commercially sensitive matters, have expressed their concern that uncertainty could deter commitments from sponsors.

Bob Lynch, a former partnerships executive at the Brooklyn Nets and Miami Dolphins, is now founder and CEO of SponsorUnited, a global sports sponsorship intelligence platform. He warned that the political environment has the potential to place obstacles in front of deals for host cities.

Lynch said: “It’s definitely something I’m sure brands are bringing to the table in their discussions with local governing bodies around their sponsorship deals. Having sat in that seat, there are always things that are potential threats.

“When you have things like that, which include the threat of leaving or pulling out, there are a couple of things that generally take place. One is that it usually slows down the decision-making process of brands at the table. They may say: ‘We need to watch and see.’ It is no different than if the economy is really struggling and people have major deals on the table or the uncertainty during Covid. So that’s a real thing. That does slow down probably conversion on sponsorship deals.

“In some cases, there are conversations taking place around, ‘If we’re in an agreement or we’re going to be in agreement, what are our rights to get out of this?’ Those are generally no different than what actually takes place within sports to guard against an earthquake taking place. It is to ensure brands are legally protected.

“I’m sure, like anybody, they would want the noise to stop. Anybody in sponsorship on the sales side is going to want the least amount of disruption. They would want that to dissipate, because that doesn’t help them sell anything.”

Chicago has no regrets about not bidding to host men’s World Cup games

In 2026, 11 cities in the United States will host World Cup games. Yet Chicago, the city with the third-largest population in the United States, will not be part of the tournament — and they appear to be quite happy about it.

The Midwest is short of representation at the World Cup, with only Kansas City, Missouri, among the host cities in that region. Chicago, which boasts an iconic venue in the 61,500 capacity Soldier Field, withdrew from the U.S.’s joint bid with Canada and Mexico in 2018, with the office of then-Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel saying in a statement at the time that it would not be in Chicago’s “best interests.”

Seven years on, Chicago’s decision-makers do not have regrets. In an interview with The Athletic, Chicago Sports Commission’s long-serving executive Kara Bachman said: “There are people who think ‘Oh my God. How are you not hosting? What’s wrong with you?’ I’m like, ‘You didn’t see what we saw.’ There was not a way to get a handle on the financials in a way I could confidently stand behind.”

She said that the deal transferred a financial burden to the city to the extent it risked “leaving us in debt.”

She also described FIFA’s terms as “demands” rather than requests and said the World Cup organizers would not accept “any changes or edits” to the contract.

“Quite honestly, I never spoke to anyone from FIFA face to face during that process, which to me was also a red flag,” Bachman added.

Soldier Field hosted soccer games during the Premier League’s Summer Series in July (Daniel Bartel/Premier League/Getty Images)

A FIFA source, who remained anonymous as they were not authorized to speak publicly on the matter, said that FIFA was negotiating with the United (United States, Canada and Mexico) bid rather than with cities directly. They also insisted that the process has been collaborative between host cities and FIFA.

Bachman warned that some of her counterparts in different host cities in America are envious of Chicago’s position in 2026. She said the requirements had “taken over” for some host cities and constituted an opportunity cost for other possible ventures.

In New Jersey, for example, MetLife Stadium, the host venue for the final, has already spent $37m (£28.4m) on upgrades to enable it to host games for FIFA. Congressman Josh Gottheimer told The Athletic in March that New Jersey will take on $65m in costs for things such as transit security for all hubs, bridges, tunnels, and airports. Miami-Dade County has already approved $46m for services associated with hosting World Cup games at Hard Rock Stadium.

Chicago has hosted other soccer events in recent years, such as the 2025 Premier League Summer Series, which Bachman says she would like to bring back to the city. Chicago is also currently part of a group of cities considering bidding to be a host city for the 2031 Women’s World Cup, which is expected to be co-hosted by the United States, Mexico, Jamaica and Costa Rica.

Yet Bachman also warned that Chicago “will not sell our soul to do it.” She said: “If they show up with the same terms, then I don’t know. If it’s the same terms, the answers don’t change.

“I don’t know that any of (the cities) have confidence that FIFA is going to look into themselves that much. I’d love to be proven wrong. Nobody seems to have the confidence that FIFA is going to be that self-reflective.”

More than half of hospitality unsold at FIFA Club World Cup

Before FIFA’s revamped Club World Cup had reached its conclusion in the summer, Gianni Infantino gave a speech at Trump Tower, New York, and declared it a roaring success.

The FIFA president said more than two million fans had “visited the matches,” with an average attendance of just under 40,000 for the 63 fixtures played across the U.S., culminating in more than 81,000 spectators at MetLife Stadium to watch Chelsea beat Paris Saint-Germain in the final.

One area that proved to be a struggle when it came to ticket sales, however, was the hospitality packages.

Ahead of the tournament, FIFA announced it had partnered with Beyond Hospitality, with Beyond’s initial press release outlining the “multiple tiers of social, premium and luxury” options available across the 12 venues.

These included a “Flagship Lounge”, which Beyond described as “the most luxurious shared commercial hospitality space available,” and “Exclusive Private Suites” offering a “five-course dining menu.”

Despite the plentiful offerings, more than 50 per cent of the hospitality tickets at the Club World Cup went unsold, according to people with knowledge of the sales.

FIFA sources, speaking on the condition of anonymity to protect relationships, highlighted that this was an inaugural tournament being held in the U.S. for the first time and there were always bound to be inconsistencies in attendance. The challenge for both Beyond and FIFA was also increased by the late planning of the tournament, with a broadcaster only announced seven months before the competition.

Beyond did not respond to a request for comment.

Dan Sheldon

Germany joins race to host Club World Cup in 2029

Despite FIFA’s many challenges in launching the expanded Club World Cup in the United States, the world governing body is confident it has plenty of options when it comes to hosting the next tournament in 2029.

FIFA intend it to be a summer competition again, which almost certainly rules out Qatar and Saudi Arabia, where the summer heat would render the games likely unplayable and require a move in the calendar to winter, as we saw with the men’s World Cup in 2022. This would bring a collision between FIFA and domestic European leagues, not to mention European football’s governing body UEFA, whose own competitions would be disturbed by the Club World Cup. For 2029 at least, this is not a fight FIFA wants.

During and following the competition in the summer, FIFA received expressions of interest from the Brazilian Football Federation, while the 2029 edition could also be used as a dummy run for Spain and Morocco, who are two of the host nations in the six-nation, three-continent bonanza that is the men’s World Cup in 2030.

Australia have also been credited with an interest in potentially hosting the Club World Cup, but The Athletic can reveal another registration has come from Germany, who most recently hosted Euro 2024.

The expanded 32-team Club World Cup was played in the United States last summer (Emilee Chinn/FIFA via Getty Images)

There are also advocates within FIFA to take the tournament to England, owing to the quality of the training bases and stadia. It may also be a way to improve relations with the Premier League, which was aggrieved by a perceived lack of consultation ahead of the 2025 Club World Cup. FIFA would also be able to rope in an additional Premier League team beyond the current country limit of two by giving England a host-country place, which was the mechanism by which Lionel Messi’s Inter Miami were invited this summer.

One of the criticisms of the 2025 edition was the absence of so many leading European names and a qualification formula that resulted in Liverpool, Napoli and Barcelona (the current champions of England, Italy and Spain) not being in a competition marketed as “the best v the best.”

There had been widespread expectation that the tournament would expand from 32 teams to help accommodate the most famous and successful teams in the world. But, for now at least, there are high-profile advocates within FIFA who believe the competition should remain a 32-team affair, but with play-in rounds to help improve the quality of competitors without removing access for confederations across the world, while the two teams per country cap may also be altered.