WASHINGTON — The Food and Drug Administration is reversing a 2003 decision that put a stringent warning on hormone therapy products for menopausal women, saying that the treatments offer heart, brain, and bone health benefits.

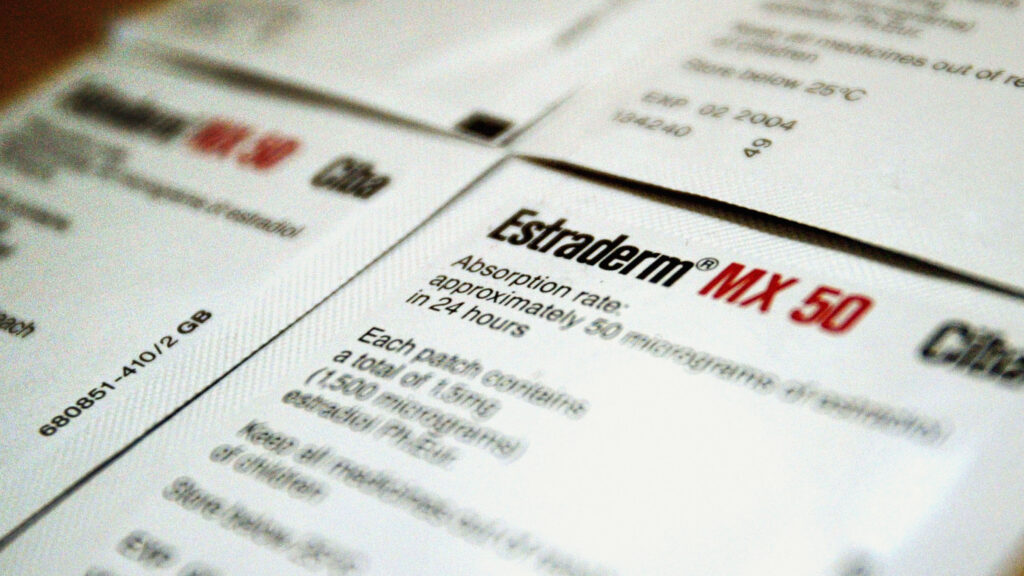

Commissioner Marty Makary wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed on Monday that the FDA is removing black box warning labels from all-combined estrogen-progestogen, estrogen-only, other estrogen-containing, and progestogen-only products used for hormone therapy. The agency said it’s asking companies to remove the warnings from their products, specifically mentions of cardiovascular, dementia, and breast cancer risk.

“These labeling revisions signal a meaningful shift toward more nuanced, evidence-based communication of hormone therapy risks—one that prioritizes clinical relevance, distinguishes between different formulations and patient populations, and balances the narrative to reflect both safety and therapeutic value,” Makary wrote in a JAMA Viewpoint also released on Monday that was co-authored with FDA staff Christine Nguyen and Tracy Beth Høeg, as well as George Tidmarsh, who resigned from the agency last week amid an investigation.

The impetus for the black box warning was a 2002 landmark study called the Women’s Health Initiative that suggested that hormone therapy came with an increased risk of heart disease and breast cancer. The study specifically focused on combination therapy among older, postmenopausal women, but the results were interpreted broadly, ultimately driving down rates of uptake for the therapies.

Since then, a growing body of research has shown that hormone therapy can actually be beneficial to menopausal women’s heart health, reducing insulin resistance and improving other cardiovascular biomarkers. These therapies can be used to alleviate menopausal symptoms including hot flashes, sleeping troubles, vaginal dryness, and painful sex.

There’s an effective treatment for menopause symptoms. Why do so few women use it?

“With the exception of antibiotics and vaccines, there may be no medication in the modern world that can improve the health outcomes of older women on a population level more than hormone therapy,” FDA officials wrote in JAMA.

For years, many clinicians have advocated for the FDA to remove the black box warning from hormone replacement products, focused largely on vaginal products like topical cream or a ring, where hormones are not fully absorbed into a person’s bloodstream.

In July, FDA officials convened an expert panel to discuss the risks and benefits of hormone therapies for menopausal women as well as opened public comments. There, physicians emphasized the relative safety of the drugs, also focusing mainly on local estrogen. Vaginal products are “categorically safe for all women, period,” said internist Heather Hirsch, adding that she believes the warnings on systemic hormone therapy are broad and poorly defined. (Hirsch founded The Collaborative, a telehealth practice that prescribes hormones to women in midlife.)

“Science evolves, and so must our warning labels,” said physician Rachel Rubin, who runs a urology and sexual medicine practice. According to the officials in JAMA, commenters reported relief with local vaginal estrogen and asked for labeling to be changed.

Some clinicians, while agreeing that it makes sense to remove the black box warning, noted that the FDA has not followed the typical process to make the decision. The panel was a short and relatively informal conversation, not a traditional scientific advisory committee to review new safety data. There were not methodologists, epidemiologists, or oncologists present, as physician and writer Jen Gunter pointed out in her blog.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has long shown support for reevaluating the label on local estrogen products, but in a comment submitted to the FDA in September, the organization “strongly encouraged” the agency to host a formal advisory committee meeting. The group also recommended an entirely separate process take place regarding systemic therapies. In a statement Monday, ACOG commended the FDA for its action.

When asked at a press conference Monday why the agency decided not to host an advisory committee meeting, Makary said it was because “ad comms are bureaucratic, long, often conflicted, and very expensive.”

“It remains essential that women are fully informed about the overall risks versus benefits,” Jacques Rossouw and Garnet Anderson, the lead authors of the 2002 Women’s Health Initiative study, wrote in a statement. The researchers don’t have an official position on the black box warning, but they note that there have been no large, randomized trials in the years since their work. “This information given should be based on the most rigorous science rather than anecdotal evidence.”

STAT Plus: How telehealth startups are trying to fill the menopause care vacuum

While the black box labels are coming off, the therapies will continue to include adverse event information, taking a more tailored approach to each therapy. Systemic hormone therapy labels will include updated information on the best timing for the therapy. Experts widely agree that it is best to initiate hormone therapy under age 60. Safety data will reflect the specific, known risks with each treatment type, as estrogen alone can have different effects than estrogen and progestogen combined.

The FDA will keep one boxed warning, for the risk of endometrial cancer when systemic estrogen is taken by a woman with “unopposed estrogen” who has a uterus. (That risk, when there isn’t enough progesterone in the body to balance out the estrogen, can be mitigated by including progestogen in a therapy regimen, officials wrote in JAMA.)

“The FDA also conducted drug utilization analyses to characterize prescribing patterns and the extent of hormone therapy use among menopausal and postmenopausal women,” the officials wrote.

“All politics aside, we are so excited for this,” said Monica Molenaar, the co-founder and co-CEO of Alloy Health, a direct-to-consumer women’s health company. Still, she’s worried that as public trust in federal health agencies dips under the Trump administration, some people may be suspicious of the change. “This really needs to be seen as a great thing.”

This story has been updated with additional information from a JAMA Viewpoint authored by FDA officials and a statement from authors of the 2002 Women’s Health Initiative study.