Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

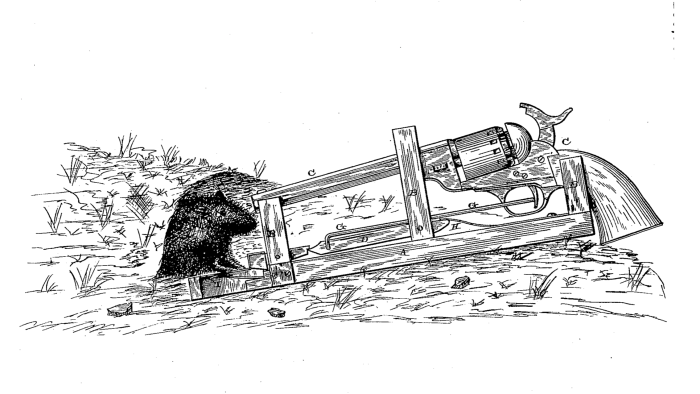

In the jargon of bank regulators, the word “mousetrap” is sometimes used to describe a model which takes the data from accounts and supervisory returns, puts it through some clever processing, and then spits out a number which might be a better measure of the risk of bank failure than the straightforward capital ratio from the accounts.

The reference is to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s proverbial statement that if you build a better mousetrap, the world will beat a path to your door. It is, of course, sarcastic — it’s actually a deliciously mean way of alluding to the tendency of clever and enthusiastic people in central bank research departments to construct these measures, and then to be surprised when their line supervisors ignore them. However superior the trap, the path usually remains unbeaten.

Anyway, check out this recent post on New York Fed’s Liberty Street Economics blog. The title is Economic Capital: A Better Measure of Bank Failure? and if you’re familiar with the genre, the scent of supermarket cheddar is unmistakable.

No such work is complete without a few charts showing how much better an early warning you get in some recent high profile cases by using the new measure, for example (zoomable version):

The blog post is linked to an absolutely painstaking hundred-page report setting out the details of how they did it. The methodology is actually quite convincing, and yet at the same time suffers from the fatal problem that always seems to bring down exercises of this kind.

The motivation for producing mousetraps is an honest one, and the problem they address is real; accounting data is backward-looking, and the obvious solution of trying to replace book values with market values as much as possible is surprisingly unworkable.

As a recent study by the European Systemic Risk Board shows, credit markets can be quite thin and volatile, and they often struggle with establishing price discovery during exactly the periods of turmoil and stress when you might want to rely on them. Sometimes people suggest making more use of the estimates of equity analysts, but this tends to fall at the objection “have you met any of them?”

So what the Fed economists do is in effect to produce a comprehensive handbook for building a discounted cash flow model of a bank’s balance sheet, taking into account the interest rate and credit sensitivity of the assets, but also the benefit of being able to keep below-market-rate deposits because of the banking franchise, and the capitalised value of the cost of maintaining that franchise.

It’s an attempt to measure the true economic value of the capital base, and as such, it’s reasonable to believe that it’s going to be a better number for that purpose than book equity based on historic cost.

However, there’s a lot that’s left out.

For example, the authors ignore the value of fee income from asset management businesses, in order to be “conservative”. On the face of it, that might seem reasonable, but in fact, the value of asset management franchises is a lot more realisable and battle-tested than almost anything that’s actually in the balance sheet. (For example, Barclays recapitalised itself and avoided a state bailout by selling Barclays Global Investors to BlackRock at the absolute nadir of the financial crisis).

And more generally, although the “economic capital” measure might have given a bit of a heads-up that Silicon Valley Bank was running quite a racy high-octane balance sheet mix, that was actually quite an unusual bankruptcy.

Most banks fail not because of something you can read in the accounts, but because the accounts themselves turned out to be very wrong as a description of reality. There’s really no substitute for a supervisor who understands the business model of the bank they are supervising, who is prepared to make judgments about that business model when it’s been pushed too far, and who doesn’t get systematically overruled by their bosses when they do.

And a supervisor like that doesn’t really get much added value from Economic Capital — or any other mousetrap measure — because it’s just telling them things they already know, in a slightly more complicated way.

It’s potentially a useful metric for supervisors who don’t have any real understanding of their banks’ business models. But it’s quite difficult from an internal marketing point of view to socialise a product on the basis of “this is really useful if you’re no good at your job”.

Which is why mousetraps fail. You can follow the instructions in the book, model about two-thirds of the risk factors affecting one of your banks, then update it every month and track trends in the economic capital. But you still have the problem of knowing when a movement is significant, and you still have the problem of understanding how it relates to risks in the real world. And then you have the problem of getting anyone to listen to you.

So it ends up like the Dustin Hoffman anecdote about Laurence Olivier listening to his experience of staying awake for 72 hours to get into the character of an exhausted paranoiac in Marathon Man and asking “why don’t you just try acting, dear boy, it’s much easier?”

Every mousetrap project, unfortunately, suffers from the problem that good bank supervisors don’t need it and bad bank supervisors don’t want it.

(The author was once a regulatory policy analyst who helped build an exceptionally good mousetrap with colleagues at the Bank of England. Thirty years later, he would like to record that he is still bitter).