At 5 A.M. on Monday, 16-year-old Yamen Al Najjar was supposed to give up his bed in the internal medicine ward of Makassed Hospital in East Jerusalem, where he’s been living for the past two years, together with his mother, gather up his paints and his few clothes and return to the devastated Gaza Strip, where he grew up.

A few days earlier, the hospital informed the two that Israel had decided to expel most of the Gazans who are hospitalized here back to the Strip. According to the nongovernmental organization Physicians for Human Rights, dozens more were to be deported with him: about 20 patients and their caregivers from Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan; 60 cancer patients and caregivers from Augusta Victoria Hospital in East Jerusalem; and 18 patients and caregivers from Makassed.

At the last minute, after CNN reported about his case, the sentence was postponed – no one knows for how long.

Yamen was born and raised in Khan Yunis, a healthy boy with an almost congenital desire to paint. In September 2017 he suffered a nose injury and bled continuously for 21 days. Bleeding also occurred in his digestive system, and he suffered from subcutaneous hemorrhaging in various parts of his body.

The medical services in Gaza couldn’t come up with a diagnosis, and after about three months Yamen was transferred to Makassed, where he was found to have von Willebrand disease, which affects the blood’s ability to clot. The life of Yamen – and of his mother – was turned upside down, but that wasn’t the end of their ordeals and torments.

We met this week in a filthy, neglected municipal garden near the hospital, amid the squalor of East Jerusalem. The boy’s mother, Haifa, elegant and charming, swings between laughter and tears, and refuses to disclose her age. Nothing in her comportment betrays the fact that she has been sharing a hospital bed with her son for more than two years, or that she doesn’t have a home. She and her husband, Ramzi, 50, a lawyer who worked in the Palestinian Authority, have four children – Yamen is the youngest.

Close

Close

Haifa and Yamen Al-Najjar at the hospital. After doctors in Gaza were unable to diagnose him, he was transferred to East Jerusalem. Credit: Alex Levac

Haifa and Yamen Al-Najjar at the hospital. After doctors in Gaza were unable to diagnose him, he was transferred to East Jerusalem. Credit: Alex Levac

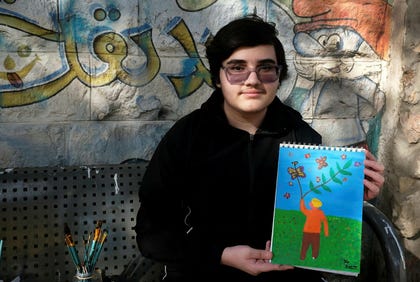

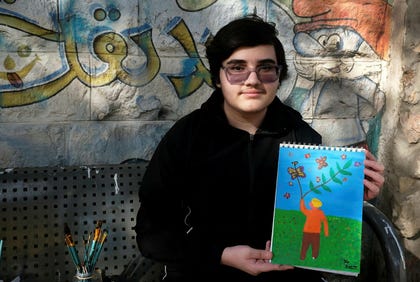

Yamen appears older than his age, with thick black hair, though the faint trace of a moustache signals that he’s still an adolescent. He’s been wearing thick glasses with dark lenses since his vision was affected by the disease. He’s carrying a plastic bag with paints and sheets of paper.

As soon as we sit down on a metal bench in the garden, Yamen busies himself creating a boldly colored acrylic painting, with occasional help from his mother, who’s also an amateur painter. By the time our conversation ends, he had completed his daily painting – a striking, beautiful work.

Related Articles

In December 2017, after being diagnosed, Yamen was transferred to Hadassah University Hospital in Ein Karem, Jerusalem. His mother tells the story vividly, remembering every date, every disease name and every symptom.

In the months that followed, the two came to Hadassah every three months to undergo tests; the trips from Gaza went smoothly and the boy’s condition was stable. But in 2020 acute new symptoms appeared, apparently unrelated to the disease he suffered from. His body temperature fell precipitously to 32-33 Celsius (about 90 Fahrenheit), and his blood pressure plunged just as dramatically, to 70/40 and even lower.

An MRI done at the Turkish-Palestinian Friendship Hospital in Gaza showed damage in his brain’s thalamus. He was taken to Istishari Arab Hospital in Ramallah, where they also diagnosed damage to his growth hormone. From there he was transferred for treatment to the hematology department in Sheba, and came there every three months for follow-ups with his mother.

The results of his tests were sent to medical centers in the United States and Canada, but he still had no diagnosis for the illness. The next step was to do genetic testing for the whole family – and then came October 7, 2023.

On that day, Yamen was a patient in St. John Eye Hospital in East Jerusalem because of his impaired vision. The next day he started bleeding again and was moved to Makassed. A few days later he was transferred to Sheba and then sent back to Makassed. He’s been there ever since. While his mother speaks, his painting progresses: He’s already done the sky and a field in bold blues and greens, and now he’s starting to paint the figure of a youth or a man. We’ll find out later.

Close

Close

Haifa and Yamen. While we talk, Yamen’s drawing progresses – he paints a sky and a field in vivid blue and green. Credit: Alex Levac

Haifa and Yamen. While we talk, Yamen’s drawing progresses – he paints a sky and a field in vivid blue and green. Credit: Alex Levac

His condition is deteriorating, his mother says. His body temperature drops to below 32 and his blood pressure plummets to 60/23. She has nightmares in which it drops to zero. He suffers from joint pain, rashes all over his body and swelling of his limbs. He sleeps 18 hours a day and any effort tires him. None of this is visible as he sits on the bench in the garden, absorbed in his painting.

Over the past few weeks, since the cease-fire in Gaza, he and his mother have been cautioned that their time here is up. They started to look for a country that would agree to take them and provide medical care for Yamen. This January he was supposed to go with dozens of wounded Gazan children to the United Arab Emirates for medical treatment, but the cease-fire collapsed, the fighting resumed and the Strip was sealed again.

Haifa contacted aid organizations and nonprofits, including the World Health Organization, Physicians for Human Rights, the International Red Cross, the Red Crescent in the UAE and in Qatar, and others. The WHO recognized the severity of his condition, but no host country has yet agreed to accept the boy. His two uncles in exile, in Britain and in Turkey, also tried to help, but so far without success.

The 22,000 children who were seriously wounded in the Gaza war have priority, his mother says, even though Yamen’s condition is no less dangerous than theirs. She also understands that his situation would be better if he were diagnosed.

Last week on Sunday it was announced that all the Gazan patients, other than the seriously ill, were going to be sent back to the Strip. Haifa was reassured, knowing that Yamen was in the serious category. But two days later, she was informed that Yamen would be deported within two days – last Thursday. On Wednesday they were told that the deportation had been postponed until this Monday, at 5 A.M.

She realized that she had to act quickly to get the decree reversed and save her son, so for the first time she turned to the international media. Abeer Salman, a producer and reporter for CNN, published the story, and immediately afterward, this Sunday, the family was informed that their deportation had been postponed indefinitely.

Close

Close

Displaced families’ tents in Muwasi this week. When the IDF entered Khan Yunis, Yamen’s family was forced to flee to Muwasi with nothing. Credit: Mahmoud Issa / Reuters

Displaced families’ tents in Muwasi this week. When the IDF entered Khan Yunis, Yamen’s family was forced to flee to Muwasi with nothing. Credit: Mahmoud Issa / Reuters

This is life in a state of anxiety, under a dark, constantly threatening cloud. “Yamen will not survive for even one day in Gaza,” his mother tells us, as tears appear on her cheeks for the first time – and she quickly wipes them away. “His whole sin is that he was born in Gaza.”

Now she’s helping him complete his painting. Yamen has painted a man holding the tree branch, with butterflies fluttering above. His mother adds another butterfly or two. Over the past few weeks he’s been painting a lot of butterflies, she says. She herself often paints sad women. One of Yamen’s works, a black-and-white drawing from a few weeks ago, shows a boy kneeling, blood flowing from his finger, a flower sprouting from cracked earth, desolate houses in the background. He told his mother that this is how he imagines the return to Gaza, with his bleeding finger.

Responding to a query from Haaretz, the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories issued the following statement: “Contrary to the claims, the coordination to return Gaza residents who were treated in Israel back to the Strip was carried out only after receiving full consent from each patient and their family, in accordance with their wishes. The patients began their treatment in Israel before the outbreak of war, and due to the closure of the crossings, their return wasn’t possible until now, even though they had completed their medical care. The process was professionally coordinated, with the required sensitivity, and in full transparency with all relevant parties.”

In other words, a “voluntary” deportation. It’s hard to believe that dozens of patients and their family members truly wished to return to a bleeding, devastated Gaza, where not a single functioning hospital remains and where it is unclear whether they themselves still have a home.

As for Yamen, a COGAT source said he was unaware of any plan to deport him. Yet Yaman and his family say they have already been told twice to pack up and prepare for deportation, most recently this Monday. In both instances, the hospital administration told them that it was acting on instructions from COGAT.

After the CNN article, a South African nonprofit expressed a willingness to help him find a place to be treated in that country, but nothing has come of this yet. For Haifa and Yamen, it’s vital for Yamen to get somewhere where he can receive medical care and also be reunited, after more than two years, with his father, sisters and brother. The phone line between them is open almost nonstop, despite difficulties with the internet in the Muwasi zone tent where the family lives. Ramzi and Yamen’s brother, Yusef, were wounded in a bombing attack in the war. On October 8, 2023, the family left their home in Khan Yunis and moved into a tent in a schoolyard that was a shelter for displaced people. But the site was soon bombed and the tent went up in flames. For a few days they slept in the street, until they were able to buy a new tent, and pitched it in Rafah, where they stayed until June 2024.

Close Credit: Alex Levac

Close Credit: Alex Levac

When the Israeli army invaded Rafah, they were forced to flee to Muwasi. They escaped without a thing and bought a new tent. During the cease-fire last January they tried to get back to the ruins of their home. There was one room left standing, so they wrapped plastic sheets around it and moved in. But when the danger increased there, they had to flee again, returning to Muwasi with a new tent.

How often do you speak with your family, we ask.

“Every time they quarrel and shout at one another, they call,” says Haifa. And Salman, the reporter, who has grown close to the family, adds with a laugh, “And that happens a lot.” They fight there, in the Muwasi tent, over a slice of bread, a space on a mattress, over who will shower and who will get something to drink, Haifa says. She tells each of them that they are right.

They had long days of disconnect from the family, and the two lived in dread. Haifa phoned everyone she knows in Gaza to ask them to find her husband and children, and listened to every news report in fear. “It was a hard time,” she says, and the tears flow again. Her husband needed a walker in the first months after being wounded. Her heart skipped a beat every time she heard about bombing and fires in Muwasi.

When Yamen is awake he paints or plays computer games with his uncles in Turkey and London. Life in the hospital is difficult. “There’s no privacy and no comfort,” Haifa says, again with a smile. Since he was 3, Yamen kept all his toys, in their original boxes. When his father and his siblings had to leave their home on October 8, all the toys were left behind. His father asked him which toy to save, and Yamen asked him to take a deck of golden playing cards. They survived until the family had to flee from the tent in Rafah, and then were lost, too.

The hospital staff is now a substitute for the family, Haifa says, but she’s trying not to get too close to them, knowing that they will have to leave. Last week, when the news of the deportation arrived, she told herself that she had done the right thing. All she wants now is for Yamen to get the best treatment possible and for the family to be reunited. He bleeds almost every day, she says, which throws him into depression.

Now he has completed his painting and signed it at the bottom.