Normal text sizeLarger text sizeVery large text size

In 1997, Ray Kinnear stood at a large whiteboard in his Exhibition Street office and mapped out an idea that would reshape Melbourne.

Victoria’s capital was already home to 3.3 million people and the transport bureaucrat was deeply troubled about its future.

Twenty years earlier, almost a quarter of Melburnians travelled to work by train, tram or bus. That had fallen to just 12 per cent.

Car use was skyrocketing. CityLink and other massive road projects dominated the state’s transport policy.

The last major improvement to the rail network was when the City Loop opened in 1981.

Former premier Jeff Kennett had just announced his intention to privatise the network. It was a grim picture.

“You can’t have a city that’s clearly going to be 5 million, if not 6 million [people], that was totally road-based,” Kinnear recalls. “That was not really sustainable in an economic sense or an environmental sense or a social sense”.

Public transport needed a major revival.

The first idea for a tunnel

Kinnear, who was the Department of Infrastructure’s director of public transport planning, had watched how Melbourne’s highway network developed, with one freeway creating political and economic momentum to build the next.

“On the whiteboard, it was that exploration to say, ‘OK, is there something big? Is there something that could leap out and grab people’s imagination?’” he says.

He scribbled an outline of Melbourne’s rail network along with existing train frequency, crowding levels, population forecasts and future demand estimates.

Quickly this revealed which part of the network would reach capacity first: the north-west corridor from Footscray to beyond Sunshine, and the south-east corridor stretching down to Dandenong.

It might take 20 or 30 years, but eventually those two lines would need more trains than could fit in the existing City Loop tunnels.

The solution was obvious: “Why not directly join those two corridors with a new tunnel?”

On Sunday, almost 28 years later, that rail tunnel will carry passengers for the first time.

From a ‘Trojan horse’ to a new dawn

The Metro Tunnel has cost $15 billion and taken almost nine years to build. Parts of the city have been shut for years at a time as 1.8 million cubic metres of rock and soil were dug from under the CBD to construct five new underground stations.

It’s the most significant change to Melbourne’s public transport network in almost four decades.

Now retired and able to reflect on more than a decade championing the project within the public service, Kinnear says the Metro Tunnel only made it off the whiteboard due to a series of fortunate coincidences.

At first, Kinnear’s superiors instructed him not to waste time on a project that wouldn’t be needed for another three decades and no government would fund.

So instead, Kinnear says he broke with bureaucratic convention and started canvassing the idea with transport industry consultants, hoping it would permeate their thinking and they would become “Trojan horses” that would smuggle it back inside government.

“That’s breaking the rules. But if you don’t do that sort of thing, you’ve got no hope changing the direction that things are heading in,” he says.

Those involved in the early stages of developing the tunnel have differing recollections about when and how they first heard about the idea. It is possible the notion of a rail tunnel developed independently among various people, too.

What is clear, though, is that by the early 2000s, the idea of a second rail line under Melbourne was fermenting and would soon bubble to the surface.

In 2002, Steve Bracks’ Labor government published the Melbourne 2030 strategic plan. It included an ambitious target to grow public transport usage from 9 per cent of all motorised trips to 20 per cent by 2020.

The infrastructure department engaged consultant William McDougall to investigate improvements to the tram network which could help this shift in travel patterns.

The Age reported on the call for a ‘tube’ line under the city on its front page on November 7, 2005.Credit: The Age Archives

Although never made public, McDougall’s resulting draft May 2003 Tram Plan said the Swanston Street tram corridor – the world’s busiest – would eventually reach capacity and the solution could involve building “a north-south underground rail link” under Swanston Street from the Domain.

This is the earliest documented mention The Age has been able to find of the concept that would evolve into the Metro Tunnel.

McDougall says he started looking at the rail tunnel a year earlier as part of a study into transport in the inner north, but that piece of work – the Northern Central City Corridor Study – was not finalised until August 2003.

The idea was thrust into Melburnians’ imaginations not long after, when the City of Melbourne hired transport planner Graham Currie to review options for the city’s transport network.

The brief included considering a proposed road tunnel linking the Eastern and Tullamarine freeways – which came to be known as the East West Link.

Currie had worked on the inner-north study three years earlier with McDougall and developed the Swanston Street rail tunnel further in his report, calling for a “north-south underground”.

The review generated a front-page article in The Age on November 7, 2005.

“Frankly, at the time people thought I was a nutter,” Currie says.

“We were messing around with tiny little changes because it’s all we could afford, when the problem was getting bigger and bigger and bigger and bigger. We needed something game-changing.”

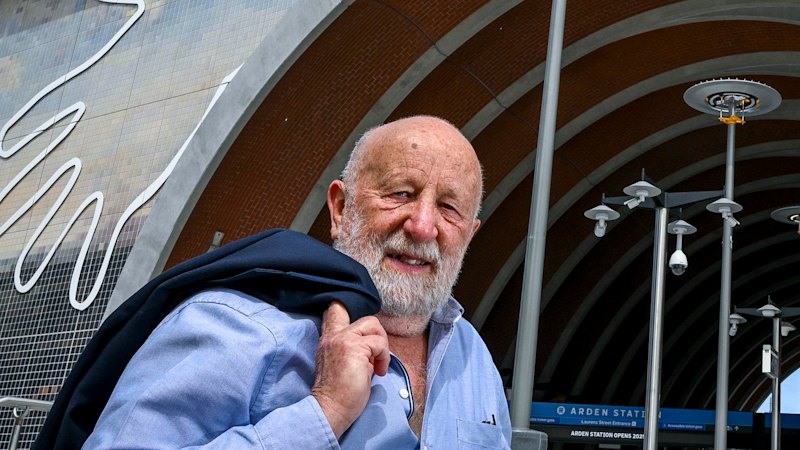

Graham Currie proposed the idea of a north-south underground for Melbourne after working in London.Credit: Eddie Jim

Currie says his thinking had been partly influenced by time spent working on London’s Crossrail.

Crossrail, since renamed the Elizabeth Line when it opened in 2022, connected two existing commuter rail corridors to the east and west via a new tunnel under central London – just like the Metro Tunnel will connect the Sunbury and Cranbourne/Pakenham lines.

Loading

A question of politics

In 2004, train use started to grow dramatically, rising 40 per cent by 2008 and more than 60 per cent by 2011. The network was struggling to cope. Chronic overcrowding and delays were becoming a political crisis.

All of a sudden, a new underground rail line looked more like a priority.

Kinnear hired consultancy Sinclair Knight Merz (SKM) and McDougall to work on an initial scoping and costing of the concept for the north-south rail tunnel in 2006.

The Age obtained a copy of the report through a freedom of information request. In January 2007, it published a front-page story revealing the Department of Infrastructure had favoured an option that included stops at North Melbourne, Parkville, the Domain and extensions to Flinders Street Station and Melbourne Central.

By 2007, Kinnear was armed with enough work on the Melbourne Metro to present it to newly-appointed public transport minister Lynne Kosky.

Kinnear says Kosky was enthusiastic and asked him to give the same presentation to a cabinet meeting a few days later.

The late former transport minister Lynne Kosky, pictured with then premier John Brumby in 2007, was an early supporter of the plan that would become the Metro Tunnel.Credit: Pat Scala

Kosky was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2011 and died in 2014. Her husband Jim Williamson remembers her sitting at their dining table one night and drawing a diagram of the City Loop on a piece of paper. “She used the expression, ‘It’s spaghetti, and it needs to be lasagne,’” he says.

There were three major projects Victoria needed to untangle that pasta bowl, she explained: first the Regional Rail Link through the outer western suburbs to separate V/Line and Metro trains.

Then would come Melbourne Metro, which Kosky called the “knowledge line” because it linked universities and hospitals in Parkville, Monash and regional Victoria. After that, a direct train line to Melbourne Airport could be built.

Despite the growing political and public interest, the Melbourne Metro remained a distant prospect.

Sir Rod Eddington bulldozed it into reality.

The Rhodes Scholar who grew up in Western Australia and went on to run Cathay Pacific, Ansett and British Airways, completed an influential transport study for the British government in 2006.

In March that year, faced with growing concerns about congestion on the Monash and Eastern freeways, Steve Bracks’ Labor government commissioned him to study transport options to improve links between Melbourne’s eastern and western suburbs.

It was widely believed among transport experts that the Eddington study was set up to help the government justify building the East West Link road tunnel under Alexandra Parade.

McDougall was brought in as a transport consultant and says it was clear on the first day where the study was heading.

“Engineers from VicRoads were already drawing copious lines on maps to see what was possible,” he says.

But he successfully argued that public transport and the new rail tunnel needed to be considered.

Eric Keys, a consultant who had been working on the Melbourne Metro with Kinnear within the department, says Eddington’s study was a golden opportunity to bypass senior bureaucrats who had been blocking its further development.

All their work on the tunnel up to that point described it as a “north-south railway”, reflecting the alignment under Swanston Street.

“So we went through all our documents with search and replace and ‘north-south’ was replaced with ‘east-west’,” Keys says.

“We packaged it all up and as soon as Eddington started work, we took it in and sat down and briefed him on it. It was an exact fit with his terms of reference. Once he endorsed it, people started listening.”

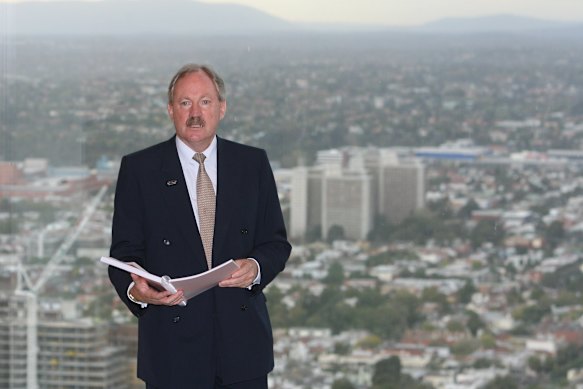

Sir Rod Eddington in 2008 with a copy of his report recommending the construction of the Melbourne Metro.Credit: Joe Armao

Eddington handed down his report in March 2008. His top recommendation was to build the Melbourne Metro: a 17-kilometre underground rail line linking the western suburbs to the south-east. The report’s second recommendation was to build the Regional Rail Link.

Eddington says that at the time, population growth across greater Melbourne and the increase in residents and jobs in the inner-city made a new underground rail project an urgent priority.

“You just can’t put any more roads in the inner city than you currently have, so you have to provide better public transport. And again, because of congestion, you’ve got to go underground,” he says.

Keys – who would later be appointed Metro Tunnel builder Cross Yarra Partnership’s chief operating officer – recalls that those who had been working on the Melbourne Metro were “absolutely elated” when the report was published.

“We felt extremely vindicated for probably what was then coming up to at least five, if not 10 years of working below the radar. That was a very exciting moment for us,” he says.

Former premier John Brumby says that the pressure on the transport system was becoming a critical political issue without an easy solution.

“Population growth occurred much more rapidly than anyone considered. In hindsight, strong economic and population growth had begun to overrun us,” he says.

In late 2008, Brumby’s government released the Victorian Transport Plan, which committed $38 billion to projects including the Metro Tunnel and Regional Rail Link.

Getting funding for them was another matter. Eddington again played an instrumental role.

The global financial crisis had unleashed on Australia and Kevin Rudd’s federal Labor government launched initiatives to keep the economy alive.

One was to direct the newly-formed Commonwealth adviser, Infrastructure Australia, to find “shovel-ready” projects to fund.

Infrastructure Australia’s inaugural chair happened to be Eddington. His advice unlocked $4 billion to build the Regional Rail Link and $40 million to develop detailed designs for the Melbourne Metro.

“It was a whole series of things that created the circumstance where it was the right project for the right time,” Keys says.

But all the momentum ground to halt in November 2010 when the Coalition won the election and stopped the project.

Melbourne Metro sat in stasis for three years. In 2014, then premier Denis Napthine announced a revised project called the Melbourne Rail Link.

Rather than travel through the heart of the CBD, to meet greatest demand, the tunnel would divert west from the Domain to Fishermans Bend then north to Southern Cross Station and on to Melbourne Airport.

This route “would have been a disaster”, says Evan Tattersall, who worked on its early plans.

“We were doing things like analysing all the high-rise buildings on Yarra’s Edge, thinking, ‘All the piles go down to rock … how the hell are we going to get a tunnel through there?’” he says. “It just wouldn’t have worked”.

Luckily for him, the Melbourne Rail Link plan was short-lived.

Labor regained power in November 2014. New premier Daniel Andrews pledged to restart the original Melbourne Metro with a tentative 2026 completion date and ripped up the contract for the $5.3 billion East West Link.

A look to the future

Tattersall was appointed chief executive of the Melbourne Metro Rail Authority in early 2015 and ran the Metro Tunnel project for its first seven years.

One of his biggest challenges, he says, was “managing up” to help Andrews and his ministers understand the enormity of what they had just committed to.

“In fairness to the government … this project is as complex as you would ever get anywhere in the world. They had no idea of how challenging it was going to be,” he says. “I say that in the nicest way and with respect. They matured, I’ll call it, very quickly as we went on.”

In December 2017, the state government signed a $6 billion construction contract with Cross Yarra Partnership, made up of John Holland, Bouygues Construction, Capella Capital and Lendlease.

Metro Tunnel project director Ben Ryan (left) and inaugural chief executive Evan Tattersall at State Library station.Credit: Eddie Jim

The first tunnel-boring machine launched at Arden station in August 2019. Just four months later, Cross Yarra Partnership downed tools and threatened to quit the project unless the government agreed to help pay for up to $3 billion in cost overruns.

The COVID-19 pandemic added further strain, causing supply chain and worksite havoc, along with cost inflation exacerbated by the war in Ukraine.

A further settlement with the builders brought the total cost to Victoria to $13.48 billion, compared with $10.9 billion when announced in 2016. CYP wore a share of the cost overruns, bringing the project’s total cost to around $15 billion.

Tattersall defends the Metro Tunnel’s management by pointing to projects of a similar scale. London’s Crossrail was 3.5 years late and £4 billion ($8.1 billion) over its £18.8 billion ($38 billion) budget. Melbourne’s West Gate Tunnel Project is set to open in December – three years late and at a cost of $10.2 billion, compared to its original $6.7 billion budget.

“The reality is, most projects would be four or five years late,” he says. “We’re a couple billion dollars over budget, which sounds bad, but it’s not compared to what you see all over the world where the budget blows out double.”

From Sunday, the Metro Tunnel will operate with a limited timetable. From February 1, full services commence with a promised “turn-up-and-go” timetable.

Time will tell how Melburnians respond. Metro Tunnel’s current project director Ben Ryan says that London’s Crossrail and Sydney’s new Metro have far exceeded patronage expectations, and the same could happen here.

“Crossrail opened three and a half years ago, and they’re at their 30-year patronage forecast, three years in,” he says.

“They’re now in London, going, ‘Wow, we need to accelerate our next investment because we’re just decades ahead of where we thought we’d be.’ It’ll be very interesting to see the take-up here. I suspect it’ll be overwhelming.”

Kinnear retired in 2015, having seen the Regional Rail Link built and a commitment to the Metro Tunnel, projects he says will nudge Melbourne towards a more sustainable future.

Loading

His concern now is whether that momentum will continue. He laments that a proposed follow-up project – the MM2, linking the south-west to the north-east – has been put on ice in favour of the massive Suburban Rail Loop, which he says is ill-conceived and will monopolise public transport funds that could be better spent.

“I think we may be halfway down the path of getting a better balance. We’ve still got a long way to go, but we’re certainly in a better position than we were 20 or 30 years ago,” he says.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.