In the first part of the investigation: On September 5 and 13, 2024, chlorine gas was used as a chemical weapon near the al-Jaili refinery, north of the Sudanese capital, Khartoum. At the time, the army was trying to recapture the refinery from the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia, their opponents in the ongoing civil war. The barrels containing chlorine gas were dropped from the sky, and the Sudanese army is the only armed group in Sudan with the aerial military capacity to carry out such a strike. An Indian company, Chemtrade International Corporation, exported the gas to Sudan. They told FRANCE 24 that the Sudanese importer assured them that the chlorine would be used “only to treat potable water”, a common civilian use for this product.

Read moreVideos show the Sudanese army’s use of chlorine gas as a weapon

Summary of the second part of our investigation

The chlorine gas used as a chemical weapon near the al-Jaili refinery on September 5 and 13, 2024, was imported by Ports Engineering Company, a Sudanese company run by a colonel in the Sudanese army.

The company specialises in public construction projects. However, it has commercial links with at least one Turkish weapons manufacturer, as well as with an Emirati company that makes the uniforms and shoes worn by the Sudanese intelligence service, according to exclusive commercial data obtained by C4ADS, an American NGO that specialises in the fight against illicit economic activity.

According to the Indian exporter, Ports Engineering claimed that the barrels of chlorine would be used “exclusively for water treatment purposes”. There is no indication that the chlorine barrels were imported for use at Sudanese water-treatment centres.

More than a third of Sudan’s population doesn’t have access to potable water, making it a critical issue across the country. Chlorine is an essential ingredient to making water fit for human consumption.

If the two barrels used in the attack had been used to purify water, they would have been able to provide potable water for six months for the one million displaced people currently in Khartoum.

From India to the battlefields of Sudan: the route of a chlorine barrel used as a chemical weapon

To trace how the barrels of chlorine ended up in Sudan, we started with a video from September 5, 2024, showing the barrel that fell on the Garri military base, located 5 km east of the al-Jaili refinery.

this video posted on Instagram September 5, 2024 by an account supporting the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia shows a barrel of chlorine that was dropped that day on the Garri military base 5 km east of the Al-Jaili refinery.

Accept

Manage my choices

In the footage, a serial number is visible on the barrel. We were able to piece together the number: “GC-1983-1715”.

This image shows how we were able to piece together the serial number on the barrel found on September 5, 2024 in the Garri military base, near the al-Jaili refinery in Sudan. The full sequence is “GC-1983-1715”. The last number is a 5 whose upper line has been erased. © Observers

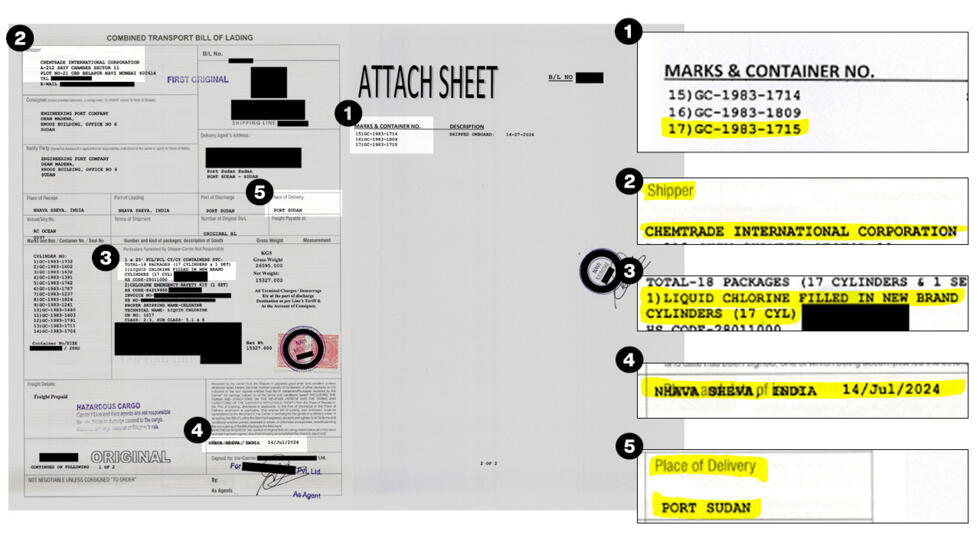

Our team obtained access to a document known as a bill of lading relating to the import of the “GC-1983-1715” chlorine barrel into Sudan. The bill of lading indicates that the barrel was shipped by Chemtrade International Corporation, an Indian company specialised in selling barrels of compressed gas. It was one of a batch of 17 barrels of the same type loaded onto a ship at the Nhava Sheva port near Mumbai on July 14, 2024, destined for Port Sudan.

The barrel with the serial number “GC-1983-1715” is mentioned on this redacted document, a bill of lading detailing when 17 barrels were loaded onto the boat that would bring them to their destination. The document contains information about the barrel: (1) Its serial number. (2) They were exported by the Indian company Chemtrade International Corporation. (3) They contained “liquid chlorine”, the form that the gas takes when it is placed in barrels. (4) The barrels were shipped from Nhava Sheva port near Mumbai on July 14, 2024. (5) Their final destination was listed as Port Sudan. © France Medias Monde graphic studio

Our team was able to examine emails exchanged between Chemtrade International and the logistics firm that managed the transport of the barrels. The emails indicated that this barrel – and the 16 others that were part of the same shipment – entered Sudan in early August 2024 via Port Sudan.

Port Sudan is the only large commercial port in Sudan. Currently, the city is also serving as the provisional capital for the army-controlled government. The barrels were moved from the port by their recipient on August 17, just three weeks before the videos appeared online showing one of these barrels at the camp near the al-Jaili refinery on September 5.

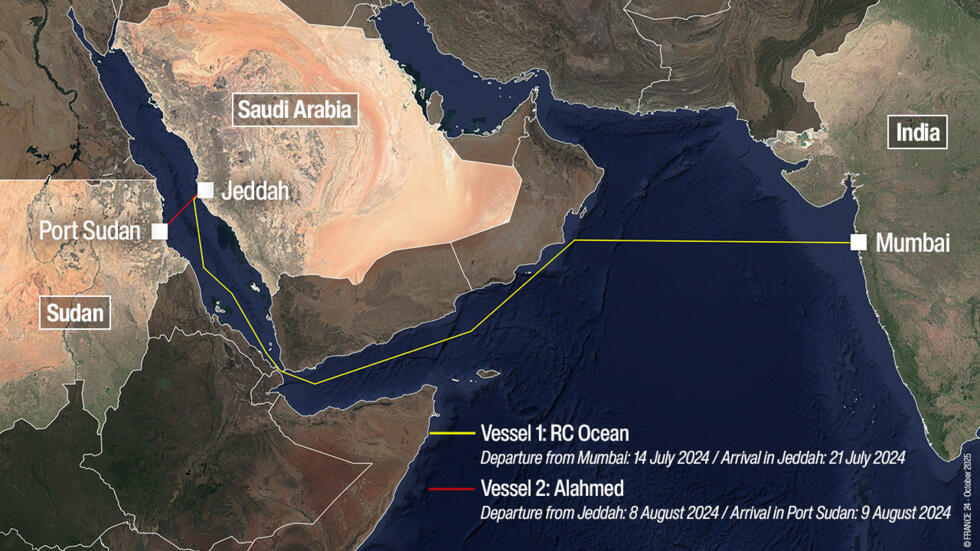

Thanks to data provided by MarineTraffic, a website that tracks ships and analyses maritime data, as well as exchanges with the companies that transported the barrels, we were able to trace the path that these barrels took to Sudan. They were loaded onto a boat called the RC Ocean in Mumbai on July 14, 2024. The RC Ocean arrived in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia on July 21, 2024, where the barrels were unloaded. A second boat, the Alahmed, then transported them to Port Sudan, where they arrived on August 9, 2024. © France Medias Monde graphic studio

Our video investigation:

Read moreExclusive: The first proof of the use of chemical weapons in Sudan’s civil war

Ports Engineering Company: a Sudanese company officially specialised in public works

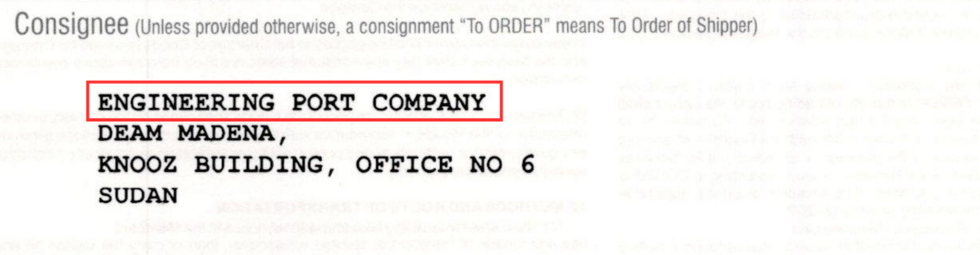

So, who were the barrels being imported for? The bill of lading provides the answer. The consignee is listed as a Sudanese company called “Engineering Port Company”, headquartered in “Deam Madena”, a neighbourhood in Port Sudan. The company also uses the name Ports Engineering Company, an alternate spelling of its Arabic name (شركة المواني الهندسية). Both names are visible on the company’s web site, which is no longer online but was archived.

The bill of lading lists the consignee “Engineering Port Company”, a company based in Port Sudan that is also known as Ports Engineering Company. © Observers

The Ports Engineering website stated that the company specialises in public works. It also mentioned other activities, including “advanced water treatment.”

Chlorine is often used to produce potable water, says Matteo Guidotti, a chemist and specialist in chemical weapons:

“Chlorine gas is used widely for peaceful means. You can use it to purify water or to produce plastic. The fact that there are civilian uses for chlorine makes it very different from the ingredients in other chemical weapons, which are often created to kill.”

Were these barrels of chlorine imported to produce potable water?

So, did Ports Engineering buy the barrels of chlorine later discovered near the al-Jaili refinery in order to produce potable water? Dhruvesh Bhonsale, the marketing director of the Indian exporter Chemtrade, says yes:

“The consignee imports chlorine cylinders exclusively for water treatment purposes under the Tawila Water Supply System [Editor’s note: located in White Nile State in the south of the country]…. They verbally informed us that they are working under a contract with the Nile River Water Board.”

The Tawila water supply system is a project that was launched by UNICEF in 2020 to provide safe drinking water in White Nile State. But a UNICEF spokesperson told FRANCE 24 the project had never worked with Ports Engineering, and uses chlorine powder, not gas:

“There are no chlorine gas dosing pumps used [Editor’s note: equipment necessary for injecting the right amount of chlorine gas into water to make it safe to drink] at Tawila, and UNICEF did not provide chlorine gas directly to the water system there. UNICEF provides chlorine powder […] for [this] system.”

The spokesperson added that “the serial number [on the barrel found at Garri military base] does not match the number of any [chlorine cylinder] imported or procured by UNICEF and was not supplied by UNICEF”.

Our team also tried to identify the “Nile River Water Board” cited by Chemtrade as being the supposed destination for the chlorine barrels. We contacted the White Nile State Water Corporation but received no response.

Ports Engineering imported 123 other chlorine barrels, location unknown

The Observers team also tried to contact Ports Engineering to ask if the company was aware that two of the chlorine barrels they imported had ended up being used in a chemical weapons attack. They did not respond to our questions.

Ports Engineering’s company website went offline during our investigation. Our team was not able to confirm if the company is continuing to operate.

The two barrels filmed near the al-Jaili refinery represent just a fraction of the chlorine imported by Ports Engineering. According to commercial data provided by C4ADS, the Indian company Chemtrade has shipped at least 125 cylinders of chlorine gas to Sudan since the start of the civil war. The company said to us by email that “all past and current transactions were handled via Ports Engineering Company only”. Moreover, no other importer of chlorine appears in Sudanese commercial data, except for the French NGO Doctors without Borders and another local company.

Accept

Manage my choices

What happened to the remaining 123 barrels – which could be used as chemical weapons but are also vital for providing potable water to the Sudanese population – remains unknown.

‘Insufficient access to the chemical products to treat water leads to epidemics’

Access to potable water is a critical issue in Sudan, where nearly 17.3 million people can’t get safe drinking water for a variety of reasons, for example, treatment facilities have been destroyed, there are frequent electricity outages and many people have been displaced by the war.

This critical shortage of potable water leads to epidemics, especially cholera. White Nile state, where the Tawila water supply system is located, was hit hard earlier this year. A total of 2,700 people, including 500 children, fell ill between January and February 2025, according to UNICEF.

That particular epidemic was a result of the RSF’s destruction of power plants. However, a spokesperson for UNICEF added that “insufficient access to the chemical products to treat water also leads to epidemics”.

We also spoke to a source who is well-informed on water production in Sudan. They requested anonymity.

“It is very difficult to obtain [chlorine] because of governmental budgets but also because you need to import these very special chemical products from abroad.”

The same source explained that a barrel containing a ton of chlorine, like those dropped near the al-Jaili refinery on September 5 and 13, 2024, could produce around 240 million litres of potable water. This would be enough to cover the basic needs for three months of the million displaced persons who have returned to the capital, Khartoum, since it was recaptured by the army on March 26, 2025.

Ports Engineering, a company linked to a group under international sanctions…

During our investigation, we were unable to corroborate the claims made by Chemtrade that the barrels of chlorine imported by Ports Engineering were originally meant to produce potable water. So we decided to find out more about the company’s other activities.

The company’s official site (which is now offline but archived) indicates that Ports Engineering is involved in “various engineering and construction contracting, import and export, mining services and stevedoring services”. It was “established in 1998 with the contribution of the Sea Ports Authority”, a government body under the Sudanese ministry of transportation that manages the country’s ports, including Port Sudan.

According to its website, Ports Engineering partnered in 2014 with “Giad Industrial Group”, a conglomerate of Sudanese public companies. Some of these have been sanctioned numerous times by France, the United Kingdom, the United States and the European Union for their links with the Sudanese Armed Forces, which threaten “peace, stability and security in Sudan”, according to statements by the French government.

Ports Engineering’s managing director (https://web.archive.org/web/20250616120700/https://ports-eng.com/en/page-team.php?show=250896147) Anas Younis is a colonel in the Sudanese army, according to several publications and official statements. Posts on social media show that he regularly meets with Sudanese officials, sometimes in uniform.

This photograph published on Facebook November 8, 2023, shows Sudanese Army Colonel Anas Younis (second from left, in uniform) at a meeting with the director of Sea Ports Authority, a Sudanese state entity that oversees the nation’s ports. © Facebook

… and implicated in the importation of military equipment

Trade data from Sudan, Turkey, India and Indonesia provided by C4ADS, an American NGO that specialises in the fight against illicit economic activities, allows us to go even further: their analysis reveals that the Ports Engineering often imports goods of a military nature.

According to examples from Sudanese import registers provided by C4ADS, Ports Engineering received a shipment in early 2024 from the Turkish munitions manufacturer Karmetal. Turkey is a known supplier of weapons to the Sudanese army for the ongoing civil war.

So did these shipments include military material? When we contacted Karmetal, they said no. They said the shipment included “empty metal boxes” and “springs” that didn’t contain “any military equipment, explosives, munitions, detonators or similar components”.

The Turkish company also said that they didn’t sell these products directly to Sudan. They say they sold them to “a customer in the Gulf region”, who then shipped them to war-torn Sudan. Our team was able to speak with the company in question, Emirates-based Bond Technologies FZE, who say that they “sold boxes and springs to Sudan with commercial use, [which have] nothing to do with any military nature”.

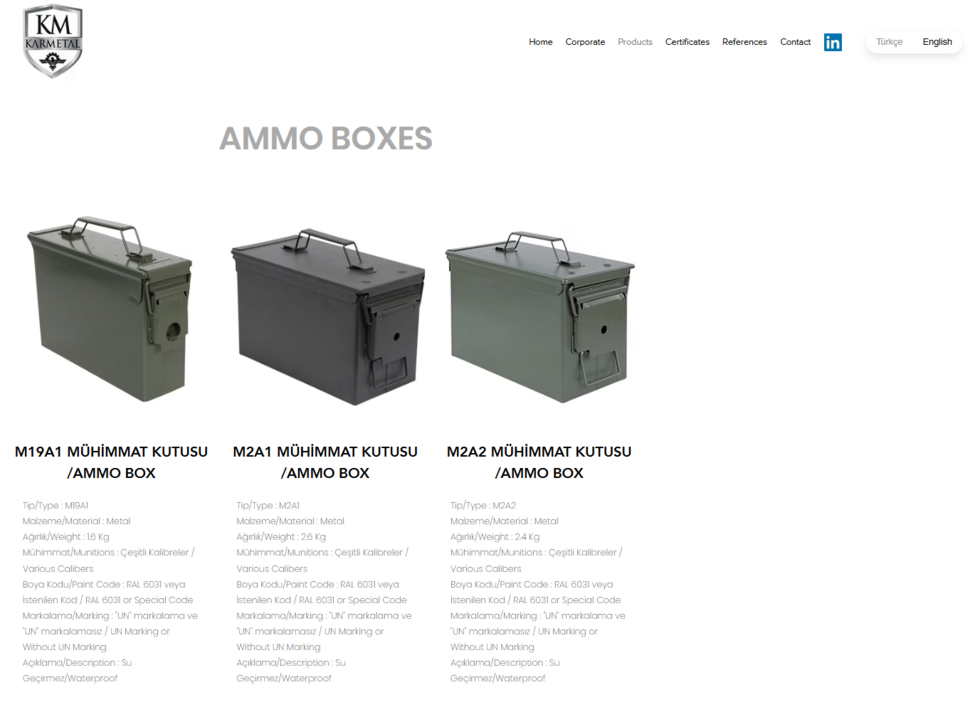

However, we found information that cast doubt on the claims made by Bond Technologies and Karmetal. First of all, the list of products manufactured by Karmetal, which is available on their site, doesn’t include anything that is solely for civilian use. We also found what Ports Engineering Company probably imported into Sudan: the “empty metal boxes” that Karmetal described in their email. However, on the site, they are described as ”ammo boxes”.

According to its website, Karmetal does indeed sell metal boxes like those that the company said they sold to a client who then exported them to Sudan. However, on the site they are described as “ammo boxes”. © Karmetal

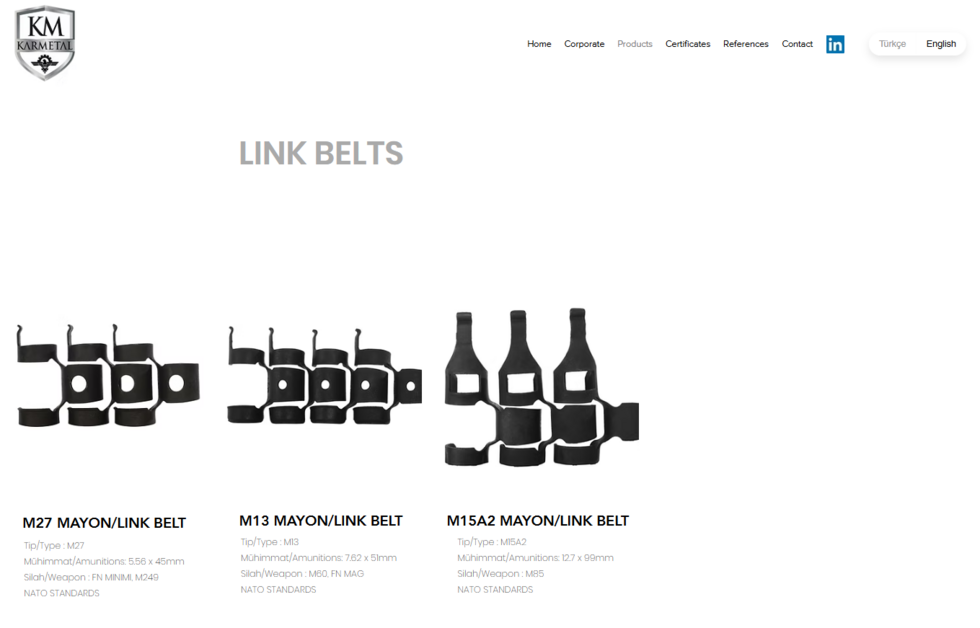

As for the “springs”, according to C4ADS, these might be “link belts” designed to hold bullets for machine guns.

Karmetal’s website displays a product called “link belts” that are designed to hold ammunition for machine guns. © Karmetal

An analyst from C4ADS told FRANCE 24:

“In trade data, these goods [the springs] are linked to a product code indicating the type of products: 731582. Notably, in Turkish records, all identified exports from Karmetal associated with this code included a description stating that they were link belts intended for feeding ammunition into automatic weapons. The sole exception is the shipment destined for Bond Technologies FZE, whose description identifies them as ‘springs’. Although it is possible that the shipment contained products other than link belts for automatic weapons, this information casts doubt on their claims.”

Our team raised these points with Karmetal, which continues, despite this information, to deny that the material purchased by Bond Technologies FZE and then shipped to Sudan contained link belts for carrying ammo or any other military material. It is, however, legal for a Turkish company to export military material to Sudan if it won’t be used in Darfur: only this region in the west of the country is covered by an international UN weapons embargo.

So, were the 125 barrels of chlorine imported to Sudan by Ports Engineering as part of its military supply business to be used as chemical weapons? Or for use in the purification of drinking water, as the company told its Indian exporter?

Without any response from Ports Engineering or the Sudanese army, it is impossible to determine.

The Observers team will update this article if any of the parties respond.