For 50 years, the Quneitra crossing — the only gate between Israel and Syria — symbolized hopes for normalcy and peace. Hundreds of Druze and Alawite brides crossed from Syria to villages on the Golan, and Druze farmers shipped thousands of tons of apples from there to Damascus and markets across the Arab world. Until the collapse of the Assad regime in December 2024, I never imagined that military vehicles would one day pass through freely — let alone that I would cross myself.

Anyone reaching the eastern buffer zone of the Golan might think for a moment they’ve stumbled into a nature film: open fields, gentle winter sun and winds spinning massive white turbines on the Israeli side of the border. But in stark contrast, on the other side of the fence and the large engineering barrier Israel is building, tension is constant and heavy.

In Syria with forces from Battalion 66

(Video: Yair Kraus)

Lt. Col. (res.) H., commander of the 55th Brigade’s 66th Battalion, calls it “the routine emergency” as he meets us near the military checkpoint before entering Syrian territory. It was just two days before the unusual incident overnight in which six officers and soldiers were wounded, three of them seriously, in Beit Jinn in southern Syria.

Lt. Col. (res.) H., commander of the 55th Brigade’s 66th Battalion, calls it “the routine emergency” as he meets us near the military checkpoint before entering Syrian territory. It was just two days before the unusual incident overnight in which six officers and soldiers were wounded, three of them seriously, in Beit Jinn in southern Syria.

In that incident, 55th Brigade forces entered the town, about 11 kilometers from the border, to arrest two suspects from the Jamaa al-Islamiyya organization. They were detained in their beds, but as the troops left the town, close-range fire was opened on their Humvee. Two officers and a reservist were seriously wounded, and three others suffered minor to moderate injuries. It was the first time since the regime’s fall that Israeli soldiers were wounded in Syria by gunfire. According to reports, nine Syrians were killed in the clashes and others were trapped under the rubble of a targeted house.

Immediately after the regime fell in December 2024, Israel began establishing 10 posts inside the Syrian buffer zone, from Mount Hermon to the tri-border area with Jordan. They were defined as “temporary,” yet the IDF presence in places like old Quneitra and the villages of Qahtaniyah and Madriya has already become permanent — and so has the expanded deployment along the border. The army is no longer satisfied with peering over the fence; it is now on the ground, patrolling, gathering intelligence and preventing militias from entrenching themselves.

18 View gallery

“The routine emergency here is the biggest challenge,” Lt. Col. H. says. “My soldiers fought in Khan Yunis in Gaza and in Khiam in southern Lebanon. In Metula, we went out every night to destroy terror infrastructure and found huge amounts of weapons. And suddenly we arrive in this country club, this safari that looks like there’s no enemy. But there is an enemy, gathering intelligence and waiting for us to be weak. There are constant alerts. You wake up to beautiful weather and civilians going to work, everything looks pastoral — until it hits you by surprise.”

The differences between Syria and Gaza or Lebanon come up in every conversation with soldiers here. “In Gaza and Lebanon, we maneuvered and fought intensely,” says Maj. (res.) A., a fighter in the 66th Battalion. “Here it’s defensive, not offensive — and that’s actually the hardest.”

“It looks pastoral, right?” he adds. “But that’s the challenge — staying tense and knowing anything can explode: an IED on the road, an attempt to seize a post or a breach into Israeli territory.”

18 View gallery

In a closed session of the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee this week, Defense Minister Israel Katz warned that, according to intelligence assessments, pro-Iranian militias — including groups linked to the Houthis — are operating in Syria. They are examining a possible ground infiltration into Israel through the Golan border. That is why, Katz said, Israel is “not on a path” toward peace with Syria, despite ongoing talks on border security arrangements. Syria is demanding that Israel withdraw from areas it seized, and President Ahmad al-Sharaa recorded a diplomatic win with a warm embrace from U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House.

While diplomacy and ground reality collide, soldiers here say a withdrawal would be a mistake. “If we leave, there will be no barrier between the enemy and civilians,” Lt. Col. H. says. “There must be an army here as a buffer. It makes it harder for the enemy to cross the entire defensive system, because if they want to harm civilians, they’ll have to go through us first. Let them try us — not our civilians.”

18 View gallery

Maj. (res.) A.

(Photo: Gil Nehushtan)

18 View gallery

Capt. A.

(Photo: Gil Nehushtan)

Lt. Col. H. has fought through two years of war. On Oct. 8, he and his troops arrived in Kfar Aza. Beyond clearing the last Hamas gunmen, they saw with their own eyes the bodies of 62 residents and had to remove them. (Eighteen soldiers were also killed in the kibbutz, and 19 people were kidnapped.) “Nahal Oz, for example, was a running distance from the fence,” he says. “The army post wasn’t between the fence and the kibbutz, it was next to the kibbutz. That’s why the principle that the IDF must be in front of civilians is not just strategic — it’s moral.”

He points eastward. Modest Syrian village homes dot the brown slopes, with chickens and stray dogs wandering between rubble and destroyed houses. In one nearby yard, gray smoke rises — with no waste collection, residents burn their trash. “Anyone living here who isn’t an IDF soldier is either part of an enemy state or an enemy,” Lt. Col. H. says. “I don’t use force arbitrarily, but soldiers know the rules of engagement. It doesn’t matter if it’s a policeman from the new regime, ISIS, al-Qaida or Hamas.”

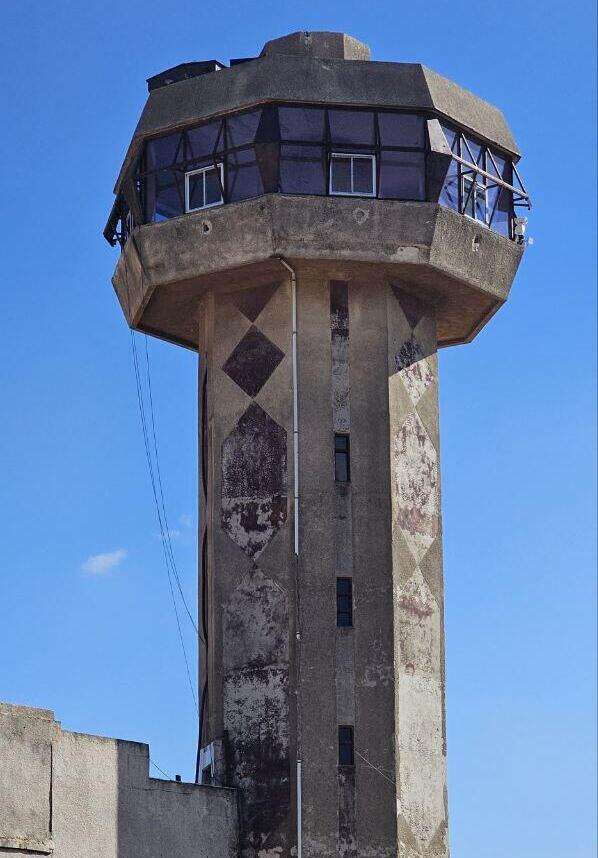

Behind us, on the Israeli side, sit the communities of Alonei HaBashan and Ein Zivan. The closeness is felt even without a map. We often pass points within rifle or mortar range of their centers. We stand in the ruins of old Quneitra, captured by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War and returned to Syria in ruins after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, under the 1974 disengagement agreement. It has been a focal point in every round of peace talks between Israel and Syria in the 1980s and 1990s. The crossing was sealed in 2014 during the Syrian civil war, when Jabhat al-Nusra seized the area for four years under its leader, then known as Mohammed al-Jolani.

18 View gallery

18 View gallery

Inside the prison

(Photo: Gil Nehushtan)

18 View gallery

18 View gallery

Assad’s photos in the Syrian house

(Photo: Gil Nehushtan)

Today, al-Jolani has shed the trappings of his al-Qaida–affiliated group and returned to his original name, Ahmad al-Sharaa. And once again, the prospect of an Israeli withdrawal from Quneitra is on the table — a possibility that deeply troubles the Israeli soldiers stationed here.

Capt. (res.) A., a platoon commander in the 66th Battalion, speaks with us as he leads a tour through firing positions, the ruins of buildings and the old Syrian police tower. “My daughter was born about two months ago,” he says almost casually. “She was born a week before the training for this deployment began. My wife is staying with her parents while I’m here.”

18 View gallery

Syrians

(Photo: Gil Nehushtan)

18 View gallery

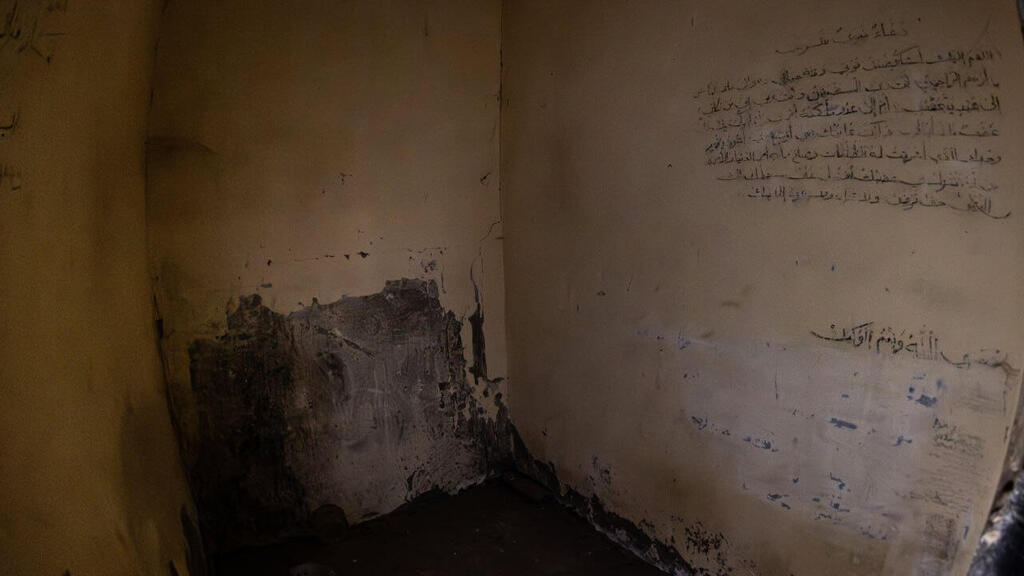

Climbing the narrow stairs to the top of the police tower, he stops beside a small room with a corridor lined with dim, cramped niches. “These were prison cells,” he explains. “It wasn’t pleasant to be a Syrian prisoner.”

On one side are the “VIP cages,” with a small opening for daylight. On the other, there are no windows at all. Each cell is roughly two meters long and one meter wide, with a hole in the floor serving as a toilet. The walls are etched with markings — tally marks of despair and Muslim prayers.

From the 360-degree lookout atop the tower, the village of al-Hamidiya is visible, with new Quneitra and the line of volcanic hills marking the border further out. Ein Zivan on the Israeli side is about a 10-minute drive. “See the wind turbines — they’re practically a stone’s throw away,” Capt. A. says. “If you don’t build depth with forces, you end up exposed.”

Not far away lives a local resident — the only one still in old Quneitra. Soldiers call him “One Tooth,” for reasons requiring little imagination. “He had two children who were killed by the police forces,” Capt. A. says. “Among residents across the sector, opinions about us are mixed. Right now, we don’t feel hostility, but we learned from the security zone in Lebanon that everything looks calm — until it isn’t.”

18 View gallery

18 View gallery

18 View gallery

Maj. (res.) Sh., a company commander in the 66th Battalion, drives us quickly through the village of Qahtaniyah toward the village of al-Madriya. We pass small homes, some damaged, alongside solar panels on lampposts. Electricity here runs only a few hours a day. “This village is a bit better off,” he explains, “but the last few years have been extremely difficult, not only security-wise. Their water reservoir is nearly empty. Most residents are farmers with no other income.”

He points to the wreckage of a school. “Most of the destruction wasn’t caused by the IDF, but by the civil war. There were heavy battles here,” he says. “We know most residents by name and face. Some IDF units provide humanitarian aid — flour, fuel and so on.”

At the foot of the nearly dry water reservoir, we meet Maj. (res.) A., another company commander from the 66th Battalion. He describes the stark contrast between life on either side of the border. “Yesterday I had a cappuccino with special milk near my home in Tel Aviv,” he says. “Today I’m meters from Ein Zivan — and it’s a different world. A different country. There’s deep poverty here. Fourteen years of civil war — you see it everywhere. And personally, the treatment of animals is hard to watch. There are stray dogs, and they also abuse donkeys.”

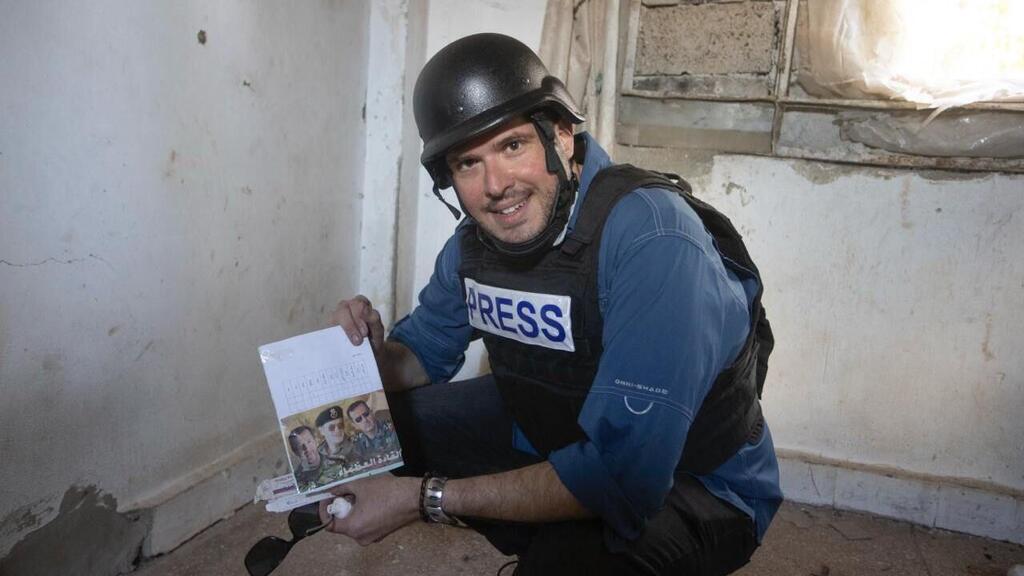

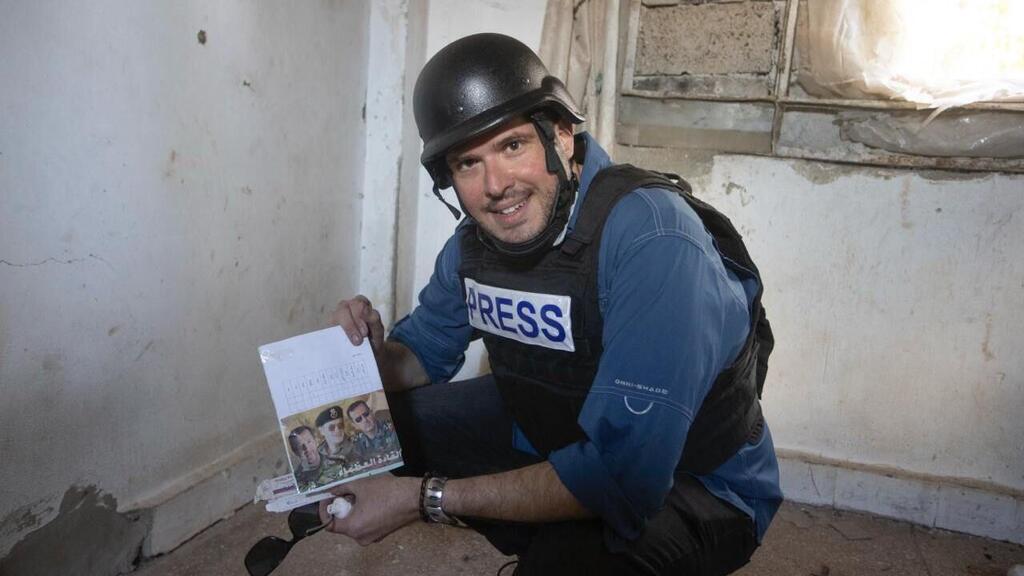

In al-Madriya, near a ruined Syrian outpost once used by Assad’s forces and a Hezbollah observation team, we find a blank prisoner assignment log from Syria’s prison system dated 2022. It includes photos of Bashar Assad and former regime commanders, captioned “our great leaders.” On a cracked concrete wall nearby, graffiti reads, “I love you, Bashar.”

18 View gallery

Our correspondent Yair Kraus with the Syrian Diary

(Photo: Gil Nehushtan)

18 View gallery

18 View gallery

18 View gallery

18 View gallery

The defensive mission here is endless and draining. It is difficult to determine who is an enemy and who is a harmless local carrying a rifle for self-defense. Forces loyal to al-Sharaa — barred from entering the buffer zone — are not the only threat. “There’s ISIS, al-Qaida, Hezbollah cells, Iranians and regime forces,” Maj. A. says. “We don’t judge intent, only capability. If someone in front of me is holding a Kalashnikov, that’s dangerous.”

He responds firmly to reports about Syria’s stance in negotiations with Israel. “There are diplomatic talks. That doesn’t interest me. As long as they have capability, we need to be prepared. That’s the core change since Oct. 7. The current defensive doctrine here is right. We need to maintain this buffer between the enemy and civilians. Our mission is to protect what’s behind us. I look west and see Ein Zivan, Ortal and Alonei HaBashan. Our routine is to stay here, stay alert and be ready for anything.”

That readiness, he says, is maintained through frequent drills. “When we’re not preparing for doomsday and looking westward, we turn east toward the enemy with operational activity.” That includes intelligence gathering, maintaining a visible presence and carrying out proactive missions. “The more you operate in this area, the farther the enemy stays from civilians. That’s the doctrine.”

This is the 66th Battalion’s third rotation, following hundreds of reserve days. Ask the soldiers if it’s hard, and they don’t complain about operating deep in enemy territory, the freezing nights or the workload. They complain about the confusion from people back home. “People in the rear think the war is over,” Lt. Col. H. says in defense of his troops. “At work they ask, ‘Why aren’t you back? The war is over, what are you still doing there?’ They think people came here to rack up reserve days and earn money. That’s not the reality. We have hundreds of soldiers in this battalion, and thousands in the brigade, who show up because they have no choice and because they understand the need.”

He is particularly angry about the treatment some of his student reservists receive at certain universities. “They say professors tell them, ‘You can’t join class on Zoom anymore, the war is over.’ It’s outrageous.” He says his forces will end 2025 with 100 reserve days and that next year’s operational demands won’t disappear. “No one knows how many reserve days we’ll have next year — 40 to 80, no one knows. We will always need a large force to defend the borders in the north, south and the West Bank.”