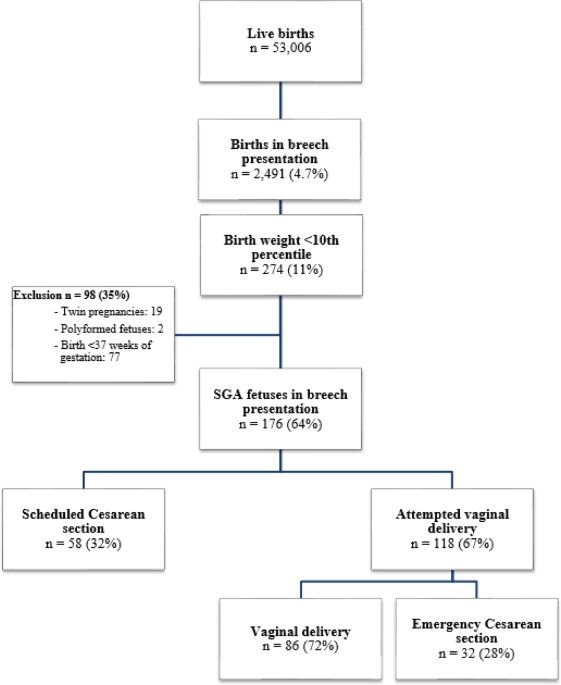

This multicenter retrospective study aimed to compare perinatal outcomes of small-for-gestational-age fetuses in breech presentation at term according to mode of delivery. Our results indicate that a trial of vaginal delivery was associated with a significantly higher incidence of low cord arterial pH (< 7.20) at birth and increased rates of neonatal hospitalization, without significant differences in Apgar scores or strict neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

The primary analysis was performed according to the intended mode of delivery, grouping successful vaginal births together with intrapartum emergency cesarean sections in the “trial of vaginal breech birth” group. This methodological choice was deliberate, as it best reflects the real-life clinical decision jointly made by the obstetrician and the patient when considering a trial of labor. Such an intention-to-treat approach is consistent with landmark studies, including the Term Breech Trial and the PREMODA cohort.

In accordance with international recommendations (ACOG, RCOG, WHO), external cephalic version (ECV) was systematically offered to all eligible women. In cases of failure, a growth ultrasound was performed at 37 weeks, followed by radiopelvimetry. Patient selection in our study was based on the eligibility criteria defined in the PREMODA study and in accordance with the recommendations of the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF)14,15. Pelvic adequacy was defined by the following thresholds: median transverse diameter ≥ 120 mm, promonto-retropubic diameter ≥ 105 mm, and interspinous diameter ≥ 100 mm Vaginal breech delivery was not considered when the estimated fetal weight exceeded 4000 g or in the presence of a multiply scarred uterus (> 1 previous cesarean). After these evaluations, structured counselling was provided, and a trial of vaginal delivery was proposed only when all safety criteria were met. During labor, continuous fetal heart rate monitoring was mandatory, and each birth was conducted under the direct supervision of a senior obstetrician physically present in the delivery room.

Neonatal acidosis was primarily defined as cord arterial pH < 7.20. Although this cutoff is less specific for predicting severe morbidity than stricter thresholds (< 7.10 or < 7.00), it remains clinically meaningful as it has been associated with adverse outcomes such as low Apgar scores, NICU admission, and the need for enhanced neonatal monitoring21,22. To ensure robustness, we also performed sensitivity analyses using stricter thresholds (< 7.10 and < 7.00, and base deficit when available), which showed consistent trends despite the reduced statistical power related to the rarity of such events (Table 7). Severe neonatal hypoxia cases were managed in accordance with national and international neonatology society guidelines, although institutional protocols may vary. In our cohort, only three such cases were identified, all of which were transferred to the University Hospital of Grenoble, ensuring standardized and specialized management. This limited number further reflects the challenges of assessing long-term neurological outcomes within the retrospective, multicenter design of our study.

Table 7 Sensitivity analysis of neonatal outcomes by mode of delivery.Comparison with the literature

Our results align partially with those of Hinnenberg et al., who reported an increased risk of neonatal acidosis for SGA breech fetuses delivered vaginally (OR 7.82; 95% CI 1–61.2) in a Finnish national cohort23. However, some discrepancies, particularly regarding Apgar scores, merit further analysis. These differences could reflect variations in obstetric protocols or cohort composition, underscoring the importance of harmonising practices for better comparisons. Methodological variations, especially in inter-observer evaluation of Apgar scores, known for their relative subjectivity, may also explain these divergences24.

The PREMODA study adhered to the criteria established by the French National College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 2000, which recommended that vaginal delivery in breech presentation be considered only for fetuses with a birth weight between 2500 g and 3800 g14. These criteria were intended to ensure optimal conditions for vaginal delivery, minimising perinatal risks. However, the cohort studied in PREMODA does not align with the population in our study. Our study includes a subset of neonates with weight deviations that fall outside the CNGOF’s specified range for optimal delivery conditions, which limits the possibility of direct comparisons between two populations. Therefore, the findings from PREMODA may not be fully applicable to our cohort of SGA fetuses, as they were not explicitly addressed in the original study.

Clinical implications

Prenatal identification of small for gestational age fetuses in breech presentation remains a significant challenge in clinical practice. The growth curves used in France during the study period did not always effectively detect intrauterine growth restrictions, regardless of the presentation. This underlines the limitations of prenatal screening, with a significant proportion of SGA cases remaining undiagnosed until birth. The recent adoption of WHO growth curves could improve screening and enable more targeted management of these pregnancies. In addition, complementary tools such as fetal Doppler assessment, amniotic fluid evaluation, and fetal heart rate analysis play a critical role in optimising prenatal detection and guiding obstetric decision-making. These parameters, along with the overall clinical context, are key determinants in selecting the mode of delivery. In cases where significant ultrasound anomalies are present—such as severe Doppler abnormalities, oligohydramnios, or signs of fetal compromise—vaginal delivery may not be the safest option, necessitating a reconsideration of the obstetric approach to prioritise fetal well-being.

In our cohort, the emergency cesarean section rate in the vaginal delivery attempt group (27%) was lower than that reported in other international studies, such as Hinnenberg et al. (40%). This result is likely the result of a centre effect, reflecting a proactive regional policy aimed at selecting patients and promoting vaginal delivery attempts. On the other hand, the high proportion of neonatal hospitalisations in the vaginal delivery attempt group (22%) highlights the need for closer monitoring when these deliveries are planned. A multidisciplinary approach involving obstetricians, neonatologists, and anaesthetists is crucial to optimise perinatal outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

Among the strengths of this study is its multicenter design, which included maternity units of different levels of care and thereby enhanced the external validity of the findings. However, this diversity may also have introduced variability in obstetric practices, potentially influencing the results.

The main limitations are the relatively modest sample size, which reduced statistical power and increased the risk of type II error, particularly for subgroup analyses; and the retrospective design, which is subject to potential selection or measurement bias despite adjustments for major confounding factors. In addition, some important neonatal outcomes—such as therapeutic hypothermia, neonatal seizures, and standardized neurological follow-up—were not consistently available across centers, limiting the evaluation of the long-term consequences of acidosis. Finally, the low rate of prenatal detection of SGA, reflecting clinical practice at the time, restricts the ability to fully assess the potential benefits of individualized management.

Future directions

More extensive prospective studies, ideally randomised, are essential to validate these results. These should include an in-depth analysis of IUGR screening methods, clearly distinguishing between SGA and IUGR, and establishing rigorous criteria for selecting patients eligible for vaginal delivery. Enhanced training for healthcare professionals on analysing and interpreting fetal heart rates, particularly by integrating approaches such as the Fetal Reserve Index (FRI), could significantly improve early detection of fetal acidosis25. By accurately identifying cases where the fetus is genuinely suffering, this approach would help reduce the excessive use of emergency cesarean sections, reserving them only for situations where truly necessary.

Finally, long-term outcomes should be given special attention, particularly neurological development and pediatric complications.