A panel that advises on U.S. vaccine policy voted on Friday to recommend a delay in when most babies begin to be vaccinated against hepatitis B, overturning a 30-year-old policy that has contributed to a massive decline in cases of the virus.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted 8-3 to recommend the change, following more than a day of contentious discussion. The new recommendation is that parents should discuss with their doctors whether to give the hepatitis B vaccine at birth, or at all, and that those who choose to do so should wait to begin the vaccine series until their baby is at least 2 months old.

That recommendation applies to mothers who test negative for hepatitis B during their pregnancy. The previous recommendation, in place since 1991, was that all babies receive a dose of hepatitis B vaccine at birth.

The change has to be endorsed by Jim O’Neill, the acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or by health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. before it becomes part of the CDC vaccination schedule.

The vote was quickly denounced by Sen. Bill Cassidy, (R-La.), a physician whose support was critical to Kennedy securing Senate confirmation. Cassidy urged federal health officials to reject it.

“As a liver doctor who has treated patients with hepatitis B for decades, this change to the vaccine schedule is a mistake,” Cassidy wrote on the social media site X. “This makes America sicker.”

The recommendation, if adopted, seems likely to deepen the fracturing in U.S. vaccine recommendations. The American Academy of Pediatrics said it would continue to advise that infants receive a birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine. And New York State’s Department of Health said in a statement that it would continue to tell medical practitioners to offer the birth dose.

The vote does not change the policy for babies born to mothers who tested positive for hepatitis B during pregnancy or whose hepatitis B status is unknown. They should continue to receive a dose of vaccine within 12 hours of birth as well as a dose of hepatitis B immune globulin.

Ending the recommendation for a universal dose of hepatitis B vaccine at birth would be Kennedy’s latest move against vaccines, and arguably the most significant to date. Before becoming health secretary, Kennedy was the founder of the anti-vaccine group Children’s Health Defense. He has been using his platform as health secretary to rapidly change vaccination policy and undermine confidence in vaccines.

The votes will not affect insurance coverage for hepatitis B shots, including under Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Likewise, the CDC said it would not affect coverage through the Vaccines for Children program.

No fresh safety concerns or effectiveness issues prompted ACIP to reconsider the hepatitis B vaccine birth dose. Instead, panelists said the review was prompted by parents concerned about the shot, the fact that most European countries give the immunization a few months after birth, and the length of time since ACIP last reviewed the topic.

Some ACIP members — including Retsef Levi, an operations management professor at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, and Evelyn Griffin, an OB-GYN from Baton Rouge General Hospital — argued that vaccinating infants against the virus was in effect requiring babies to face a risk because society hadn’t managed to come up with programs that drive the virus out of the adult population in the United States.

Throughout the discussion there were repeated claims from ACIP members who voted against the birth dose that the risk to most babies was very low and that hepatitis B is largely a disease of sex workers, drug users, and immigrants from countries with high rates of infection.

STAT Plus: How two top FDA officials are quietly upending vaccine regulations

All pregnant people are supposed to be tested for hepatitis B during pregnancy. But testing doesn’t always occur, some test results are faulty, and some pregnant people become infected later in pregnancy, after being tested, resulting in babies slipping through the safety net meant to protect them against infection at birth.

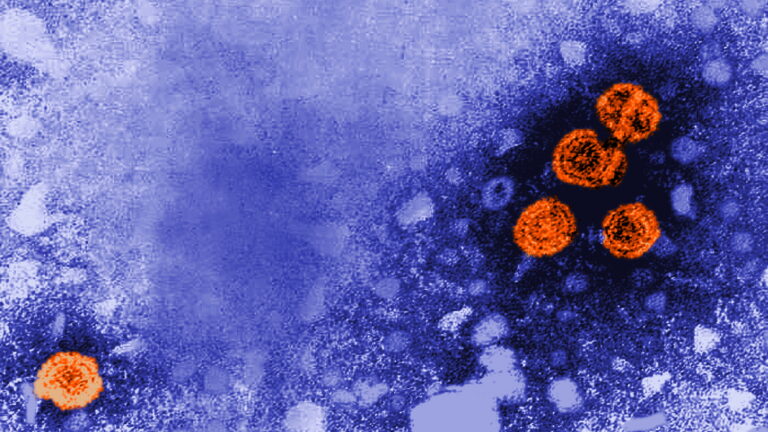

After the birth dose policy was adopted in 1991, the number of infants and babies who tested positive for hepatitis B plummeted into single or low-double digits, from the thousands.

James Campbell, vice chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on infectious diseases, said the new policy, if added to the CDC’s childhood vaccine schedule, will put children in harm’s way.

He noted that before the birth dose policy was adopted, he cared for a 15-year-old girl in Baltimore who had become chronically infected with hepatitis B. The girl, who hadn’t been vaccinated in infancy because it was not believed she was at risk of contracting the virus, died after having two failed liver transplants.

“This is a very dangerous decision. It will certainly cause harm,” Campbell said. The AAP, which has nonvoting liaison membership on the ACIP, has been boycotting meetings of the group since Kennedy fired the previous panel.

Cody Meissner, an ACIP member who is a pediatrician, said there are abundant data to suggest the vaccine is safe and that the risk to babies from the virus is real.

Meissner was joined in his opposition to the change by Joseph Hibbeln, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist, and by Raymond Pollak, a surgeon and transplant specialist, who did not detail his opposition to the change.

A modeling study posted online late last month estimates that delaying the start of hepatitis B vaccination by two months could lead to more than 1,400 babies becoming chronically infected with hepatitis B in the first year of the change, which could result in 304 cases of liver cancer and 482 hepatitis B-related deaths among those children as they age. The study is a preprint; it has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

An estimated 90% of babies infected in infancy become chronically infected with the virus, which can lead to liver disease and premature death from liver cancer or cirrhosis. About a quarter of children chronically infected in early life will die prematurely from liver disease.

Many liaison members — representatives of the professional organizations that have direct interest in vaccination policy — also argued against the change.

The ACIP meeting bore little resemblance to those of the past, with CDC subject matter experts effectively sidelined or silenced, and data presentations being made by people with ties to the anti-vaccine community but little expertise in the assessment of vaccine data.

At the beginning of Friday’s session, acting chair Robert Malone noted that two prominent proponents of vaccines — and critics of Kennedy and the new ACIP — had been invited to make presentations to the committee. But both Paul Offit, director of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Vaccine Education Center, and Peter Hotez, director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, declined the invitation, he said.

Offit told STAT the request was made via his hospital’s speaker’s bureau in October, and did not indicate when he would be asked to address ACIP or on what topic. But even if he’d known he was being asked to speak to this meeting, he would not have agreed, he said.

“I don’t want to legitimize what I think is an illegitimate process. I don’t want to be part of a process that gives bad advice, that’s putting children in harm’s way,” Offit said.

Hotez told the New York Times he declined the invitation for similar reasons.

At times during the hepatitis B discussion, the committee acknowledged they didn’t have data to support some of the things they were recommending — the suggestion, for instance, that the first dose of hepatitis B not be given before a baby is 2 months old.

A similar situation arose with the second vote put to the committee, a recommendation that parents who choose to vaccinate their babies against hepatitis B should ask for a serology test of the baby after the first dose, to see if additional doses are actually needed. The hepatitis B vaccine for young children is given in a three- or four-dose regimen.

Several ACIP members — including new chair Kirk Milhoan — conceded there are no data to suggest that a single dose of the vaccine would provide long-lasting protection. The recommendation appeared to be crafted on the understanding that some babies achieve an antibody titer after one dose that is believed to be protective after three doses. But Meissner noted that all the studies looking at the effectiveness of the vaccine were done on the three-dose series.

“We have no idea if less than three doses of the vaccine will be protective,” he said.

Adam Langer, a CDC subject matter expert who was asked to comment on the proposal, agreed, saying the committee “would be making a real huge assumption” to conclude that data generated after three doses of vaccine would apply to a single dose, and create durable protection.

Milhoan said he would have been comfortable voting instead to recommend that the issue of whether three doses are needed should be studied. But he didn’t propose an amendment to the voting language, and voted with the majority of the committee to make the recommendation. It passed by a vote of 6-4, with one abstention.

Later on Friday, Aaron Siri, an attorney with ties to Kennedy, led the committee through a sweeping, 76-slide presentation that broadly addresses the childhood vaccine schedule. In the slides, Siri invited the committee to consider revisiting “prior recommendations made without robust data” and requiring “robust trial and, when possible, post-licensure safety data.”

An ACIP working group, which includes people with ties to vaccine-skeptical groups, is currently reviewing the entire schedule. It’s not yet known what changes to the childhood vaccine schedule the committee may decide to consider.

Daniel Payne and Chelsea Cirruzzo contributed reporting.