This summer Kimberly Prost, a Canadian judge at the International Criminal Court (ICC), arrived at her home in The Hague and, as was her habit, called out “Alexa”.

There was silence. The voice-activated assistant did not respond. “Alexa was dead. She wouldn’t talk to me,” Prost recalled in an interview with The Irish Times.

Prost had been added to the United States’ sanctions list, because in 2020 she ruled to authorise an investigation into possible atrocities in Afghanistan, including by US troops. Amazon, obliged to implement the sanctions as a US company, had cancelled her account.

It was just the start of what Prost describes as a “pervasive, negative effect” of the sanctions across all aspects of her life, which has shut her out from much of the international banking system.

The effects of being sanctioned are wide-ranging.

“You immediately lose your credit cards – it doesn’t matter where they were issued or by what bank,” Prost said. Bank transfers can be challenging: a sum of money she tried to send a young couple as a wedding gift has been lost in the system for weeks.

“Online shopping becomes excruciatingly difficult, if not impossible. But there’s other things, everyday things, like ordering an Uber or ordering tickets for something, or booking a hotel.”

“If you have assets in the United States, then they’re frozen,” Prost said. “If you have family or family who works there, visits there, there’s a real danger. One of my colleagues, her daughter’s visa was revoked.”

Sanctioned court staff are from countries including Senegal, Benin, Peru, Fiji and Uganda. Sending money to their home countries has become difficult.

“I can’t buy US dollars, but also I can’t buy some other kinds of currencies, because the transaction would go through the US system,” Prost said. “So for some of my colleagues who are sending money, perhaps to South America or Africa, they have that problem.”

Prost stresses that these relatively minor issues compared with the matters she hears about in cases before the court.

“These are small annoyances, but when they all come together at once in your life, it’s paralysing,” Prost said.

“The purpose is clear. They have said, basically, we’re imposing these sanctions because of decisions you’ve taken in your role as a judge. So effectively, they are interfering directly with the independence of a judge,” Prost said.

“I can’t think of any other way to describe it but an attack on the independence of the judiciary and the International Criminal Court’s independence as an institution, which is why I’m so interested in the public hearing this.”

Prost was added to the sanctions list in August because five years ago she was one of the judges who ruled to authorise an investigation into alleged war crimes by the Taliban, Afghan forces, US forces and the CIA in Afghanistan since 2003.

The US has sanctioned six ICC judges this year, along with the court’s chief prosecutor and two deputy prosecutors.

Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu. Photograph: Abir Sultan/EPA

Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu. Photograph: Abir Sultan/EPA

The reasons given by the state department relate either to their roles in the Afghanistan investigation or their involvement in the court’s issuing of arrest warrants for Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu and former defence minister Yoav Gallant in November 2024 for the war crime of starvation as a method of warfare in Gaza, and for crimes against humanity.

[ ICC judges wanted Netanyahu arrested. Now they’re being targeted by TrumpOpens in new window ]

The US and Israel reject the jurisdiction of the court. Neither country is among the 125 signatories of the Rome Statute, which established the ICC in 1998. However, the treaty sets out that nationals of non-member states can be tried for crimes that take place on the territory of states that are signatories.

Afghanistan signed it in 2003 and the state of Palestine in 2014. The court therefore asserts its jurisdiction to prosecute the crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and crimes of aggression that have taken place in Gaza, East Jerusalem or the West Bank, no matter the nationality of the alleged perpetrators.

In an executive order announcing the first round of ICC sanctions this year, US president Donald Trump said the court represented an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States” for its investigations into nationals of the US and Israel. The state department accused the court of conducting “lawfare” and infringing on US sovereignty.

Along with the ICC staff, the US also sanctioned three Palestinian NGOs for engaging with the court in its efforts to “ investigate, arrest, detain or prosecute Israeli nationals”. The court is preparing for the possibility that the ICC itself might be sanctioned as an entity any day.

Originally from Winnepeg, Prost was a public prosecutor in Canada and became specialised in the prosecution of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. She served as a judge on the United Nations’ International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, which led to the conviction of multiple people for carrying out a genocide in Srebrenica.

[ ‘I’m remembering Srebrenica while Srebrenica is happening in Gaza’Opens in new window ]

For five years, she was the ombudsperson for the UN Security Council’s al-Qaeda sanctions, something Prost calls “an odd background twist that makes this very ironic”.

“Basically, my job was to speak to people who wanted to come off the list,” Prost said. “So I know sanctions very well.”

There is a psychological impact on ICC staff, who have spent their lives working within the criminal justice system, when they suddenly find themselves on a sanctions list alongside people implicated in human rights violations, terrorism or organised crime.

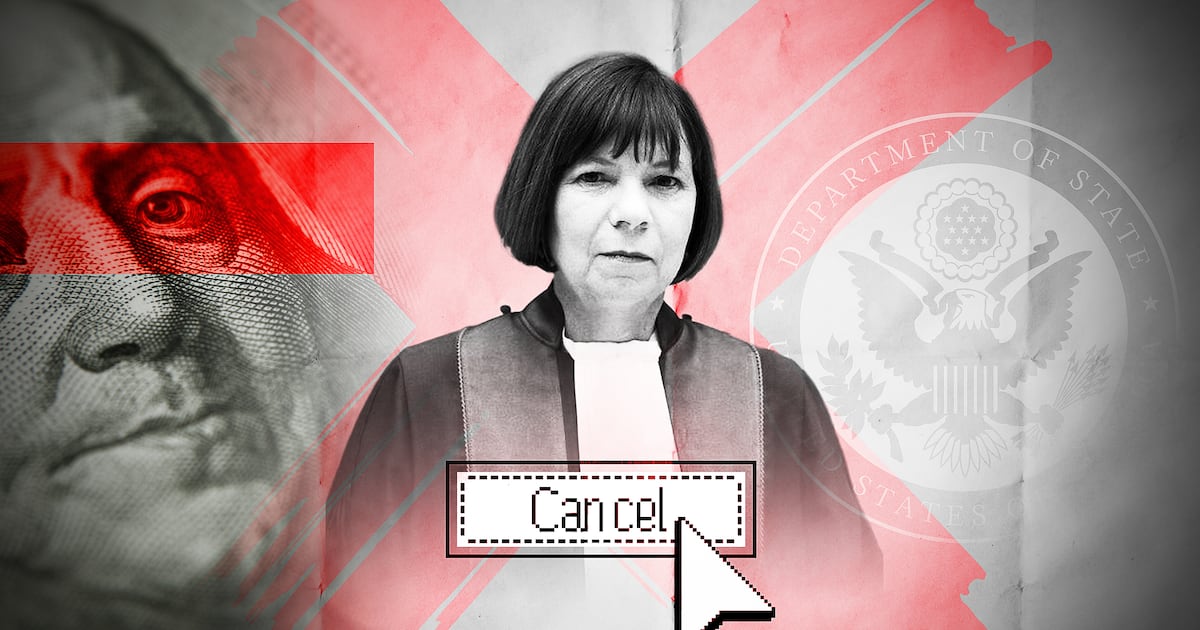

Kimberly Prost. Photograph: ICC

Kimberly Prost. Photograph: ICC

“It’s a bit surrealistic,” Prost said. “Now you’re on that same list. So yeah, it’s a bit shocking.”

Prost was part of the Canadian delegation when the Rome Statute was first agreed in 1998. It was the culmination of a century of efforts to establish an international court to try individuals for the worst crimes in the world, a permanent version of the one-off courts established to try the Nazis in Nuremberg and the perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide.

[ When Nazism went on trial: the Irish journalist in the room at NurembergOpens in new window ]

At that time, the negotiating countries had their differences, Prost recalled, but were united in their overall aim.

“[They believed] there should be a system designed to bring accountability for the gravest crimes: crimes against humanity, war crimes, genocide,” she remembered. “There should be an end to impunity. And that’s what infused the entire negotiation.”

Something that sticks with her from her time as a judge is the testimony she heard that led to the conviction of the former head of the Islamic police force that governed Timbuktu in northern Mali when the historic city was overrun by a jihadist takeover in 2012.

Al-Hassan ag Abdoul Aziz was convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity for overseeing torture, public amputations and floggings.

“I was sitting in a courtroom having witnesses come from Timbuktu, who’d never been outside of Timbuktu, to testify,” she remembered.

“The power of that testimony, and hearing those victims … standing up and expressing their rights and expressing over and over again: we want justice.”

Court staff are familiar with challenges to their work. Russia retaliated to the court’s issuing of arrest warrants for president Vladimir Putin and military leaders for atrocities in Ukraine by issuing arrest warrants for ICC staff.

Former ICC chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda. Photograph: Toussaint Kluiters/AFP/Getty Images

Former ICC chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda. Photograph: Toussaint Kluiters/AFP/Getty Images

Former prosecutor Fatou Bensouda has said she was subject to threats and intimidation after she opened an initial inquiry into atrocities in Afghanistan and by Israeli forces.

However, the US sanctions are unprecedented. Prost has not ruled out litigation in the US, as she believes the legal basis to the sanctions is questionable, though this would be hugely expensive.

She hopes that speaking openly about the effect will galvanise supporters of the court to defend it and limit the effect of the sanctions. Some of the implementation of the measures outside the US is discretionary. The judge believes it is very important that there is no perception that powerful developed countries are exempt from accountability.

“That would damage the court, if we’re unable to do cases equally wherever justice demands,” Prost said. “This is about a basic need, the imperative of justice for all of us.”