This summary of where we’re at was originally presented at a City Vibes event run by The Urban Room on 9th December 2025, and like all our work, is brought to you by the Greater Auckland crew and made possible by generous donations from our readers and fans.

We’re now a registered charity, so your donations are tax-deductible. If you’d like to support our work – and, what better time of year to make a gift for a better world? – you can join our circle of supporters here, or support us on Substack.

We’re a quarter of the way into the 21st century. The big whole-of-region Auckland Council is 15 years old; Auckland Transport 1.0 is dead, being eaten by its parent, as is Eke Panuku, its separate urban design and development agency.

Greater Auckland took off around the same time as the Supercity, running as a sort of unofficial parallel.

So what is this moment? Are we at an end, a beginning, or both? For the urban reshaping of our city. Are we there yet? Are we actually in this new century, prepared to leave the certainties of the previous one behind? Is this a city?

To me this is the end of the beginning. A kind of pivotal moment, an in-between. We are fully pregnant with the 21st century city, but just not quite yet full term.

Critically, the City Rail Link (CRL) is built, with the city being reshaped around it, but it is not yet running. Even so, imagine, an actual Metro in a New Zealand city! The transformation of a barely viable little freight network into a kind of Metro, even extended a little, all electrified with modern European trains and a city centre tunnel – the barely believable joy of it!

Karanga-ā-Hape Station and plaza, complete but not open, Dec 2025. Photo: Patrick Reynolds

Soon we really will have an actual high-order urban public transport system able to deliver meaningful numbers of people through our city – on a somewhat eccentric pattern, true, largely shaped by geographic and historic happenstance. Nonetheless this is new, a dislocation from 20th century Auckland. A time when serious moves were taken to close the whole legacy rail network down and pave over the thing. We had mayors and transport ministers actually pitching this. The contrast between these periods is enormous.

This partial rail network is being complemented by bus rapid transit: three major routes, two operating at least in part, and one as a ‘start-up’ pre-rapid service, with a permanent way in planning. With the three rail lines, this gives us a six route radial RTN. From zero, last century.

Imagine, a city.

Auckland Transport’s representation of the coming Rapid Transit Network.

Beneath this, and doing much of the heavy lifting in terms of ridership, is the balance of the bus system. It’s easily the most comprehensive, effective, and efficient in any Australasian city. Auckland now has an almost unimaginably good bus system, not just in patches, but nearly everywhere, and not just radial, but now serving cross-town routes too. Cleverly improved through near constant evolution, by some very smart, very dedicated people. Supported by wise funders and elected members (shout out here to the Climate Action Targeted Rate, set up by the previous council that delivered the latest expansion). This fact is still something of a secret, but is starting to break through.

Auckland Frequent Transit Network 2025

Electric buses are gradually replacing the loud and stinky older ones, which is a truly great thing for everyone across the city, whether they use them or not, especially for anyone who enjoys breathing. As well for those concerned about whole-of-life costs and public finances. Electric ferries are being added across the sparkling Waitematā from their expanded downtown hub too, transforming the experience of crossing the water.

Associate Transport Minister Julie-Anne Genter and Mayor Phil Goff at an e-bus launch 2018. Photo: Patrick Reynolds.

In my view, these upgrades mean that for many journeys and most times, there are now sufficiently viable public transport alternatives to always having to drive, especially for high-demand destinations like the city centre.

Significantly this means our city is ready for the best tool to mange the scourge of traffic congestion: road pricing, known officially as Time of Use Charging. For only with sticks can carrots truly work, when driving is otherwise so incentivised.

This is a very big change, and a huge opportunity.

Te Komititanga, outside Waitematā station. Photo Patrick Reynolds

These new public transport systems have also delivered an actual real city square downtown, where they meet. A well designed grand communal space that has instantly worked from the moment it opened, perfectly framed by the Edwardian edifice of the re-purposed Central Post Office, a public building, that looks like a public building, with a new public use, adorning a public space.

People flood this space naturally, doing everything and nothing, Te Komititanga and Waitematā Station together are an object lesson in world class civic reinvention through the marriage of well planned public services, infrastructure delivery, and high-quality design.

Imagine, a city.

Waitematā Station and Te Komititanga. Photo: Patrick Reynolds

To me, too, the very conscious Te Reo Māori branding of these important new places is clever and valuable. Particularity is essential in public goods. Be more Auckland. Sameness plagues the contemporary built environment. What differentiates Auckland from Aakron, or Adelaide?

There is nothing that can more authentically differentiate Tāmaki from other cities around the globe as effectively than foregrounding this land’s first language and culture. Especially as it, and the dominant colonial culture, are growing together into new shapes, each under the influence of the other. Fight me.

Tūrama, on Queen Street. Photo: Auckland Council

So at last our city has a clear civic heart, and some sense of itself. Somewhere obvious to celebrate, or protest, or party, or mourn, together. This is new. Auckland was literally centreless, heartless, and soul-less, pre-Te Komititanga. And it took the CRL to deliver this.

Form follows transport.

World Choir Games 2024. Photo: Patrick Reynolds

We have also added all sorts of other new people spaces, some leafy and inviting, some compact and enclosing, others long and connective. Both in the city centre, and in a number of suburban centres. We have managed to actually win back some street space from its almost total loss to motoring and parking last century.

Again, a lot of this has come with the CRL: city re-invention requires a burning platform, and in the need to re-shape streets around stations, by definition a pedestrian-first programme, the CRL provided that necessary imperative. Just as importantly, that the opportunity has been taken.

Which requires vision. To realise vision requires institutions shaped to deliver it. Here I think is the right moment to praise Len Brown’s mayoralty (including deputy Penny Hulse and others), and the Auckland Design Office, and Ludo, the individual, but also the very idea of the office of ‘urban design champion’. An office I think Auckland would still benefit from, though perhaps renamed.

Takutai Square in Britomart. Photo: Patrick Reynolds

I have nothing but praise for the City Centre Master Plan, the enduring product of this set-up. It’s a perfectly weighted document: specific enough to be useful, but general enough to be endorsed. It hit at exactly the right altitude. It may be under attack now, yet its tangible successes are clear to see across the city. The CCMP should of course be iterated, as an evolving and learning document.

Also, we absolutely should carry out a whole lot of post-completion evaluations on all it has delivered so far. Once the CRL is open and has run for a decent period, we will be able to measure the effectiveness of the changes.

Till then, we have little reason to change course, beyond a few tweaks (e.g. the timing of traffic signals, to facilitate easy movement of people and public transport in particular). Because, even without the supporting purpose of an operating CRL, the city’s new spaces that have been completed are already self-evidently successful – witness Quay Street and Te Komititanga below where I’m speaking from.

Even though we are in a weird sort of interregnum – after the old, but before the new – there is literally every sign that the strategy of reorienting some public realm to people and place is already working here. This is best seen downtown, as this is where the supporting public transport services are already operating.

Te Wānaga, a new harbourside public space, with the Quay St upgrade, plus additional ferry berths beyond. Photo: Patrick Reynolds

What this all shows is that Auckland functions exactly as cities do everywhere across the globe. We are not special. We too, can function outside of a car. People in quantity outside of vehicles are the key economic metric for city success. The homo sapiens of Auckland are proving themselves more than capable of fulfilling this role.

Imagine, a city.

Meola Road, multimodal, functional, smart. Photo: Jolisa Gracewood

Pt Chevalier Road, ditto. Nice, neighbourly, the new normal. Photo: Jolisa Gracewood

We have some dedicated bike paths, really good ones in places, I am beyond grateful for the recent Meola Rd and Pt Chevalier upgrade, for example. There are many other great little moments, including on two really important long routes, to the NW, and out to the east, which is getting a new high quality link at the moment. Were this London, they’d be called Cycle Superhighways, and branded CS1 and 2, and yes we should do that too.

Work under way on the final connecting section of Te Ara ki Uta ki Tai, the Glen Innes to Tāmaki Drive Path. Photo: Patrick Reynolds.

In general, this is our most underdeveloped network of all. Alhough – counts show that even this partial system now brings as many people into the city centre daily as the ferry system does. At a fraction of the operating cost. Truly, the stealth transport mode and place-uplifter.

Completing a minimum viable cycleway network across the city should be a near-term council goal. Bang for buck. It the cheapest missing network to add [Ed: leveraging the enormous road renewals budget for maximum value is the obvious place to start]. The capital cost of cycleways only gets higher when they are over-built [and/or located away from places people live and want to access], just to preserve absolute driving and parking priority.

The Auckland Cycleway Strategy Map: one thing to note is that every major waterway or body of water on this map is now crossable on foot and by bike. Except for one.

The same is true for the urgent task of completing the Rapid Transit Network. The Eastern Busway and the in-planning NW Busway are both massive space-and-treasure-eating engineering projects. That’s because they are not transforming existing road-space, but are on new alignments, often requiring massive acquisition and demolition of existing buildings. Moreover, they’ve been directed to not only work around existing road systems, which already take the cheapest, easiest, and most direct routes – but even include their further expansion.

This is in contrast to the transport revolution of the post-war era, when the existing transport systems – and much else – were demolished to make way for the new mode. Now, we are just complementing the current dominant mode. This is the most expensive way to change things.

This point demands a deeper discussion. Here, I will just say that this is extreme rich-country behaviour. We are not having hard conversations here, especially around climate. We are attempting to fully indulge everyone – we are trying to do it all. I see this everywhere at the moment: we seem to live in an age that believes it can avoid trade-offs. Is this realistic? Have your fossil fuels and eat them too?

Form follows transport, but is also bound by regulation.

On this issue we have at last the possibility of significant city-enabling planning reform, in the form of PC120. Happily, thanks to the earlier Unitary Plan, plus some brave investors, we do have a few examples of what a more urban Auckland could be like – not just urban, but maybe even urbane? This is a big change for the advocates among us; no need to always rely on offshore examples.

45 Mt Eden Rd ASC Architects. photo Patrick Reynolds

45 Mt Eden Rd ASC Architects. photo Patrick Reynolds

45 Mt Eden Rd ASC Architects. photo Patrick Reynolds

We even have in The Spinoff , and Simon Wilson, mainstream-ish media spaces and voices that discuss these things in ways beyond the tiresome tropes of Bernard Orsman’s ratepayer-funding shock-horror.

So, we can say Tāmaki/Auckland has a more varied and interesting bunch of personalities today. This is a city transformed, I feel we can proclaim this, should proclaim it now.

Transforming still, of course: city is really a verb, cities are always in a state of becoming, or declining, often both at once; they are unstable entities. That’s the dynamic and exciting thing about city life – change and the new are always there, at least as possibilities: Statluft mach Frei.

But.

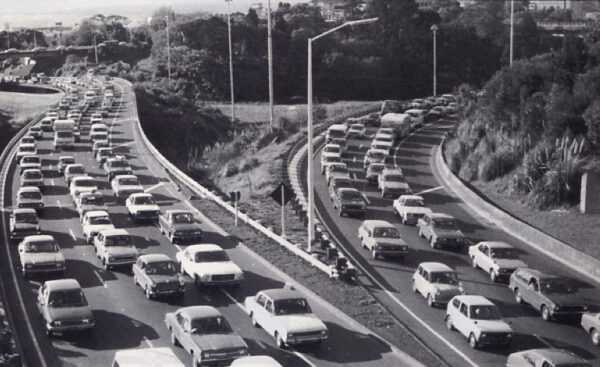

This is an additive change. The late 20th-century city is still there, with plenty of momentum, sprawlling on, living bumper-to-bumper, stand-alone house to mall. Out on the edges, it is still growing fungus-like, eating more of the productive and beautiful countryside, fed by its ever expanding motorway enabler.

This is not some Etch-A-Sketch transformation where the previous city is erased and then replaced by something completely different. New skin is growing, but the old one is very far from shed. The old lizard lives on beneath its upstart new one.

Some people live largely in last century’s city still, perhaps ignoring the new city sprouting up around them, perhaps dipping in and out of it. This is to be expected. This is how change happens, outside of sudden dislocations through war or natural disaster (or unnatural ones, like what the US Interstates did to their cities).

Others, however, live entirely in the old world, determinedly unchanging, viewing anything outside of this norm as an incomprehensible outrage, a bafflement, as something no one sensible could want. Therefore inexplicable, outside of conspiracy or culture-war framing: wokeness, and always described as an appalling waste of money, their money, of course. This leaves them ranting and muttering at each innovation witnessed through their windscreen, to Hosking, et al. Some of this group are politicians. Which is also to be expected; complaint attracts attention, and gets rewarded. So it goes. Colonel Blimp.

Culmination.

So we are at a really significant point, in my view. Now, 2025/26, marks the end of the beginning. This thing is actually now airborne, and maybe unstoppable? We can more than pretend it’s a city, or imagine we could one day have one – we can actually live it.

The hardest part has been done. The start. As Keynes said:

The problem isn’t in the search for new ideas, it’s in getting away from the old ones.

Let me be clear, additive change is a good thing: it is much less dislocating, and we should retain what is valuable from the previous age – but only within reason, and if momentum is maintained. Stagnation is the alternative, and stagnant cities die. We do need to envision the future and build the necessary institutional muscle, capability and capacity, to continue the realisation of those visions.

As Thomas Carlyle said:

Go as far as you can see; when you get there, you’ll be able to see farther.

Keep imagining, a city.

Ngā mihi nui

Patrick Reynolds, The Urban Room, December 2025

Downtown, moving, changing. Photo: Patrick Reynolds

Share this