In the midst of the Falklands War, British sailors hunting for ARA San Luis launched ordnance at the sonar and radar signals of whales, wrecks, and even flocks of seagulls — anything that might have been a submarine hiding in the cluttered, shallow seabed or skulking along the jagged coastline. Capt. John Francis Howard, commanding officer of the British frigate HMS Brilliant, would later recount his “total frustration” at the chaotic nature of his crew’s hunt for the elusive Argentinian diesel-electric submarine.

The war remains one of the very few real-world examples of post-World War II submarine combat and is rife with lessons for contemporary naval planners. Most notably, unlike the classic convoy battles of the 1940s, what made the difference in this conflict was not the marathon endurance of the submarine crews, or the number of torpedoes they carried on board, but the peculiar physics of shallow water. In messy littorals — full of wrecks, kelp forests, and irregular seabeds that raise the ambient noise level — the side that can operate close to the bottom, exploit these natural disturbances, and survive the inevitable anti-submarine hunt after firing holds the decisive advantage.

In such environments, loading a submarine with a very large torpedo arsenal brings serious drawbacks: greater draft, stronger acoustic and magnetic signatures, and narrower maneuvering margins near the seabed. All too often, any gain in firepower is cancelled out by a loss of stealth and survivability, especially in crowded, shallow littorals.

Three episodes from the Falklands campaign illustrate this logic clearly. ARA San Luis managed to slow down a superior British task force for weeks, despite firing only a handful of torpedoes. The elderly ARA Santa Fe, a World War II-era boat, was quickly neutralized because it was simply too large for the coastal shallows in which it was forced to operate. Finally, HMS Conqueror’s torpedo attack that sank the cruiser ARA General Belgrano removed Argentina’s main surface threat in a single stroke and reshaped the naval campaign.

ARA San Luis: Small, Silent, and Strategically Disproportionate

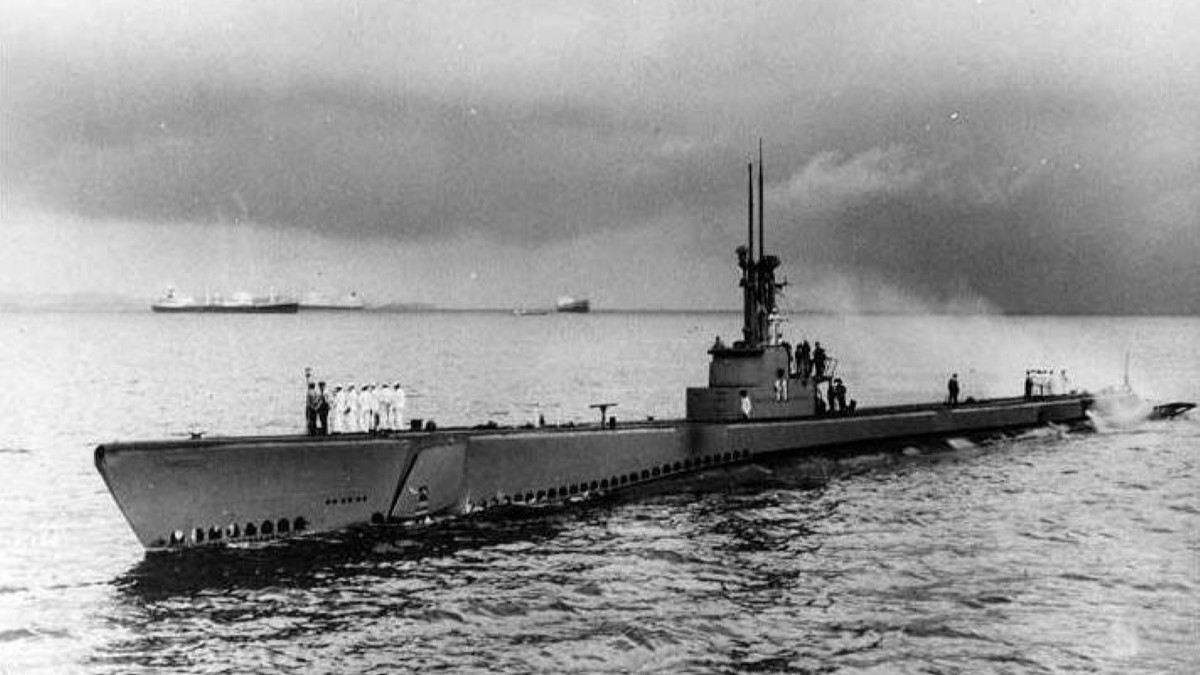

ARA San Luis was a German-built diesel-electric submarine of about 1,200 tons, deployed in mid-April 1982 with a relatively inexperienced crew and several serious defects — including a failed fire-control computer, which forced the crew to fire torpedoes manually in emergency mode.

For almost a month, ARA San Luis patrolled silently to the north of the Falklands, exposing itself only for three isolated attacks, on May 1, 8, and 10. None of these shots resulted in a confirmed hit. The first two torpedoes failed due to technical issues, and the third struck only a towed acoustic decoy deployed by a British ship.

Yet despite the lack of hits, ARA San Luis had an enormous strategic impact. On May 1, after its first shot, the submarine triggered an intense day-long anti-submarine hunt by British forces: dozens of depth charges and multiple torpedoes were launched at suspected positions, many of them based on false or ambiguous contacts in the noisy environment. During this time, ARA San Luis lay silent on the seabed at roughly 70 meters depth, using the irregular bottom and high ambient noise to mask its presence.

More broadly, the mere possibility that ARA San Luis might be lying in wait forced the British task force to move more cautiously. The presence of a single silent submarine slowed operations, consumed valuable anti-submarine warfare resources, and forced escorts and carriers onto more conservative routes and dispositions. This amounted to a form of sea denial — the denial of assured control of the sea — achieved by just one quiet diesel-electric boat.

ARA Santa Fe: When Shallow Waters Punish Size

If ARA San Luis showed the advantages of a compact, quiet submarine, the story of ARA Santa Fe illustrates the opposite problem: what happens when a large, aging boat is forced to operate in very shallow coastal waters.

ARA Santa Fe was an old-World War II-era diesel-electric submarine, originally built for the U.S. Navy and later transferred to Argentina. In April 1982 it was sent to resupply the Argentine garrison on South Georgia Island and land reinforcements. Sailing on April 16, ARA Santa Fe managed to slip through British anti-submarine surveillance and complete the mission, delivering troops and material to the island.

The real crisis came on Apr. 25. After unloading men and supplies, ARA Santa Fe attempted to withdraw from the area. However, the waters around South Georgia are extremely shallow, with depths of only around 40–50 meters in key channels. For a submarine of roughly 2,500 tons, this was simply not enough water to safely dive and maneuver.

With limited battery charge and unable to submerge effectively, ARA Santa Fe was forced to remain on or near the surface, moving slowly. In that condition, it became an easy target. British helicopters attacked with depth charges and anti-ship missiles, quickly causing serious damage. The submarine lost propulsion and began taking on water. With no way to escape or fight back effectively, the crew had no choice but to beach the submarine and abandon it. They soon surrendered to British forces.

The lesson is fundamentally about physics, not age. A large submarine that cannot dive in shallow water becomes an almost defenseless target. A smaller boat, with a shallower draft, might have had the option of hugging the seabed, taking advantage of the irregular bottom and environmental clutter to hide or slip away.

My own experience as a submarine commander confirms this principle. With a small submarine (Toti class), I could begin the dive with as little as roughly 30 meters of water beneath the keel. On larger submarines (Sauro class), we would wait for at least 70–80 meters of depth before submerging, in order to maintain safe vertical clearance from both seabed and surface. In coastal scenarios, those extra meters can make the difference between escaping and being detected and destroyed.

HMS Conqueror vs. ARA General Belgrano: Undersea Control Decides the Campaign

On May 2, 1982, the British nuclear-powered submarine HMS Conqueror torpedoed and sank the Argentine cruiser ARA General Belgrano. The ship went down rapidly with hundreds of sailors on board. The operational and psychological effects were enormous.

In the wake of the sinking, the Argentine aircraft carrier and all major surface units halted operations and retreated to home ports. Virtually overnight, the Argentine Navy’s main surface threat was removed from the open ocean. That single attack fundamentally changed the course of the campaign.

With the enemy’s surface fleet effectively neutralized, British submarines could maintain control of the waters around the islands, while British carriers and amphibious units maneuvered with much greater freedom. From that point on, the main axis of the conflict at sea shifted into the air domain.

When British forces launched their amphibious assault at San Carlos on May 21, they faced determined attacks from Argentine aviation, but no naval challenge from surface warships. A single successful submarine attack had force a major fleet to retreat, reshaping the entire campaign.

Undersea Lessons from the Falklands

The three distinct episodes in the Falklands war point to a series of broader — and still relevant — lessons and insights on the conduct of undersea warfare.

First, shallow water can be a great equalizer. High ambient noise, wrecks, kelp, and irregular seabeds degrade sonar performance, lengthen detection timelines, and make torpedo end-games less reliable. Even a navy as experienced as the Royal Navy struggled to locate and destroy a small diesel-electric submarine resting on the bottom and using the environment to mask its own noise — exactly what ARA San Luis did on May 1, when it settled at around 70 meters while helicopters and frigates dropped bombs and torpedoes on false contacts above.

Second, size matters — but not always in the way one might think, as larger boats are, in fact, often disadvantaged near the coast. ARA Santa Fe (around 2,500 tons) could not safely dive in 40–50 meters of water and was quickly neutralized by helicopter attacks. In contrast, ARA San Luis (around 1,200 tons) was able to remain near the seabed in less than 100 meters of water, repeatedly escaping detection and attack. Below roughly 70 meters, evasion becomes difficult for a large hull because of its deeper draft, greater inertia, and stronger signatures. Generally, a smaller, quieter submarine is far harder to detect and track, creating disproportionate problems for both surface ships and other submarines.

Third, the threat-in-being embodied by even one submarine can have disproportionate effects, even on occasion tying down an entire fleet. With only two operational submarines at sea, Argentina forced the Royal Navy to spread its anti-submarine assets across dozens of ships and helicopters. On May 1, the British employed multiple torpedoes and dozens of depth charges in an unsuccessful effort to pin down ARA San Luis in the shallows. This asymmetric effect is deliberate: A quiet submarine multiplies its impact far beyond the few torpedoes it carries. It compels the enemy to conduct continuous detection, classification, and attack cycles — often against false alarms in a difficult acoustic environment.

Fourth, firing opportunities are scarce, and stealth is everything. During nearly a month of patrol, ARA San Luis found only three opportunities to attack, and each time it could fire a single torpedo. Carrying a large load of weapons on board is often of limited practical value in such circumstances. The extra volume and noise associated with a very large torpedo battery can reduce a submarine’s ability to exploit those rare, fleeting windows where a shot is actually possible. In shallow water, after launching a torpedo, survival becomes the main challenge. A small, agile, and quiet boat has a far higher chance of slipping away than a larger submarine burdened with weapons it may never have time to use. In this sense, “right-sizing” the magazine to the number of shots a submarine can realistically take makes more sense than simply maximizing the number of tubes and weapons.

Fifth, undersea dominance shapes the surface fight. After the sinking of ARA General Belgrano, Argentina’s main surface units stayed in port and did not come out again. Carrier operations were suspended and planned naval attacks were cancelled. British forces thus gained freedom of maneuver at sea and could concentrate on countering Argentine airpower and supporting amphibious operations. Once again, control of the undersea domain translated directly into operational freedom above the surface.

Finally, in littoral waters the heavy torpedo remains the weapon of choice. Launching a missile from a submarine in coastal waters immediately reveals the general area of the firing platform, because the missile must break the surface and its launch signature is visible to radar and infrared sensors. This exposes the submarine to rapid counterattack. In many cases, the trade-off is not worth it. A heavyweight torpedo, by contrast, remains covert. It travels underwater and detonates beneath the target’s hull, often with devastating effect. In the coastal environment, the heavy torpedo therefore remains the most effective and survivable weapon a submarine can employ.

The Future of Undersea Warfare

Future submarine warfare is unlikely to resemble the convoy-hunting campaigns of World War II. It is far more probable that the next undersea battles will take place in confined littoral seas where current crises tend to concentrate — such as the Baltic, the Black Sea, or the Arabian Gulf — and in the coastal or archipelagic choke points of the western Pacific. These theaters are characterized by shallow depths, high levels of ambient noise, and a cluttered seabed.

Under these conditions, the physics of the environment penalize large platforms and reward submarines that can operate close to the bottom, exploit terrain masking, and disappear quickly after firing.

This is precisely why the Falklands War remains so instructive. Fought in a shallow-water context, it provides a rare, real-world case of how submarines can survive and exert influence in such conditions. Its lessons remain valid today, as a number of contemporary Chinese scholars and military analysts have observed. By contrast, combat in the deep, open oceans demands a different set of characteristics in terms of endurance and payload. Looking beyond the operational lessons, however, what insights can tease out for the future of submarine force design?

Implications for Submarine Force Design

First, if future conflicts are likely to unfold in shallow, “dirty” waters, navies should prioritize submarines that can operate and hide in that environment. A boat of only a few hundred tons can maneuver in 30–50 meters of water, where a conventional 2,000-ton submarine has limited room to turn, trim, and conceal itself. The larger boat has greater draft and a larger acoustic and magnetic footprint — in shallow water it simply cannot maneuver or hide as effectively. After firing, it has fewer options to evade.

This does not mean fleets should rely solely on midget submarines of under 100 tons. Such very small craft excel in specialized roles — special forces insertion, sabotage or mining in ports — but lack the space, power, and crew capacity to carry a full set of sensors and engage in prolonged combat operations. The ideal combat submarine for littoral operations should strike a balance: small enough to disappear near the bottom, but large enough to carry modern sensors, communications, and a sufficient crew.

In littoral environments, firing windows are few and brief. Designing a submarine to carry 12–14 heavyweight torpedoes means adding volume and displacement that rarely translate into actual kills. It is more sensible to equip a compact submarine with a modest but modern arsenal, emphasizing quiet launch systems, immediate post-shot concealment, and high-quality sensors and training to seize the right moment. A smaller, quieter boat with “enough” weapons — rather than an oversized load — is more likely to be ready, undetected, and survivable when those crucial moments arrive. A larger submarine weighed down by unused weapons may never be in a position to employ them effectively.

The extensive use of unmanned underwater vehicles can complement these manned platforms. Unmanned underwater vehicles can provide additional sensing, act as decoys, and carry a limited number of weapons, all while remaining difficult to detect. Several navies are already investing in large, long-endurance unmanned programs, such as the U.S. Navy’s Orca extra-large unmanned underwater vehicle, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Manta Ray demonstrator, and Israel’s BlueWhale autonomous submarine. Designed to loiter for weeks, sweep mines, patrol chokepoints, and guard seabed infrastructure, these systems push much of the risk and attrition away from scarce, high-value manned submarines. Together, compact manned submarines and distributed unmanned underwater vehicles can form a resilient and lethal undersea force tailored to the physics of the littoral.

Conclusion

In future conflicts fought in confined and coastal seas, the decisive undersea assets will likely be compact submarines that are extraordinarily hard to find and destroy, yet capable of imposing heavy costs on much larger naval forces. Small enough to hide near the seabed, but large enough to carry full sensors and a modern torpedo outfit: This is the configuration recommended by the Falklands experience. A new generation of 300-ton compact submarines can now exploit similar littoral physics even more effectively: they retain the ability to disappear in cluttered coastal environments, but overcome the classic limitations of midget boats or unmanned underwater vehicles in endurance, payload, command and control, and sensors, thus making them the true leading edge of submarine development and the most dangerous undersea adversaries in littoral warfare. Once again, these conclusions apply primarily to the littoral domain. In the open ocean, endurance and payload still matter greatly. Many of the world’s most likely theaters for future maritime confrontation, however — from the Baltic and the Arabian Gulf to large parts of the South China Sea — are shallow, noisy, and cluttered.

In those increasingly contested and crowded waters, the stealth achieved by staying close to the seabed and maintaining strict acoustic discipline may matter more than displacement or the sheer number of weapons carried — just as it did in 1982.

Liborio F. Palombella is a retired admiral of the Italian Navy with a long operational career in submarines and surface combatants. He commanded both the 500-ton Toti-class submarine ITS Dandolo and the 2,000-ton Sauro-class submarine ITS Pelosi, as well as the anti-submarine warfare frigate ITS Scirocco and the destroyer ITS Duilio. He later served as head of the Evaluation and Analysis Team at the Italian Navy Training Center and as head of operations at the Italian High Seas Fleet Command. He holds master’s degrees in Maritime and Naval Sciences and in Political Science, and a postgraduate master’s in Strategic Studies.

Image: U.S. Navy via Wikimedia Commons