Listen to the Trump administration’s rhetoric about vaccines and you’ll hear a refrain. In September, what replaced the government recommendation that everyone over 6 months get an annual Covid shot? “Shared clinical decision-making.” What’s at the heart of timing kids’ immunizations, according to National Institutes of Health director Jay Bhattacharya? “Shared decision-making.” In early January, what filled the vacuum when federal authorities abruptly stopped broadly endorsing vaccines against rotavirus, influenza, meningococcal disease, hepatitis A, and hepatitis B for kids who aren’t deemed high-risk? “Shared clinical decision-making.”

But to researchers who’ve spent their careers advancing shared decision-making, federal health leaders may be distorting the concept. At its heart, it involves clinicians giving their patients accurate information about the various options before them, and then the two parties collaboratively articulating a plan built on both the scientific evidence and the person’s own goals and preferences.

Experts worry that recent changes disregard the important role of evidence. “It is a common misconception about shared decision-making that it somehow means that we are not supposed to or allowed to give a recommendation,” said Leigh Simmons, medical director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Health Decision Sciences Center.

Because the term has often been associated with gray areas, in which no one option is most medically advisable, many are concerned that the federal government’s usage gives a false impression of balance, suggesting — inaccurately — that the decades of data behind something like the hepatitis B vaccine is equivocal about its benefit.

“What you don’t want to do is to hijack the idea,” said Glyn Elwyn, a co-founder of the International Shared Decision Making Society and a professor at Dartmouth.

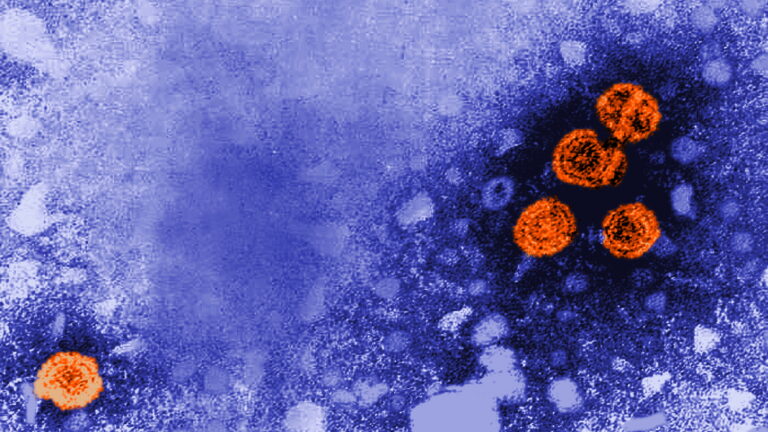

STAT Plus: How do we know mRNA vaccines are safe and effective? An explainer

The phrase “shared decision-making” is sometimes traced back to a 1972 essay by philosopher Robert Veatch entitled, “Models for Ethical Medicine in a Revolutionary Age.” At the time, there was a growing sense that medical care was a right — and, with near-miraculous advances in vaccine development, neonatal care, heart surgery, and organ transplantation, to name only a few head spinning changes of the previous decade, there was a growing belief in the life-altering power of medicine. If not every case demanded the same treatment, but every patient had an equal moral claim to dignity, freedom, and individuality, how to bring civil rights into the exam room?

The atomic bomb and Nazi medical experimentation had shown that science — and by extension, medicine — could not be untethered from ethical values, Veatch wrote. Nor would individual autonomy allow for the patient to look up to the doctor as to a priest. The two weren’t colleagues, exactly; that obscured the imbalance in knowledge and power at play. Rather, he suggested, the relationship should be more like a covenant, “a real sharing of decision-making” that harmonizes the patient’s values with the physician’s expertise.

Within a decade, federal advisers had taken up the idea. A government commission, initially convened to address research abuses — the Tuskegee study, for instance, in which participants’ syphilis was deliberately left untreated — had expanded its remit to study gnarly clinical questions, such as what constituted death and when to continue or withdraw life-sustaining treatment. They eventually turned to medical decision-making writ large.

“In the 1960s, there was a terribly strong presumption to go off what the doctor said. They were doctor’s orders. People who had cancer were not always told they had cancer,” said geriatrician Joanne Lynn, now retired from a professorship at George Washington University. By the time she became assistant director of the commission, in 1981, “there were a number of court cases that established informed consent, but how to have it work in practice was still in flux.”

The old paternalism no longer seemed ethical, but nor did leaving patients to make high-stakes, probability-tangled decisions by themselves. “One of the things we were addressing was the tendency to engage in kind of an information-dumping on the patient,” said Alexander Capron, then the commission’s executive director, now professor emeritus at University of Southern California. “This was partially as a result of regarding informed consent as mostly a protection against liability, and equating informed consent with the consent form.”

To the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, informed consent needed to be more meaningful. Its 1982 report proposed shared decision-making as a possible answer: an in-depth process merging clinician’s know-how and patient’s values. It was neither paternalism nor customer-is-always-right consumerism. Patients couldn’t insist on something that violated the practitioner’s professional standards or morals. This was autonomy buttressed by evidence and clinical acumen.

As shared decision-making became a field unto itself in the ensuing decades, it came to connote something different from plain old informed consent. Though it might be used as a tool during an informed consent conversation, it was often associated with scenarios in which a clinician saw more than one reasonable option and no obvious standard of care. Informed consent should happen all the time, the patient receiving information and able to ask questions before accepting a treatment. Shared decision-making is informed consent on steroids, honed for the gray areas.

A classic example is prostate cancer screening by testing for a biomarker called PSA. Elevated PSA levels might indicate passing inflammation or the presence of cancer. To find out requires invasive testing that carries risk. Even if there is a tumor, it might be something that the patient would die with, rather than die of. Some more aggressive cancers don’t raise one’s PSA; others do. Treating prostate cancer may cause incontinence or sexual dysfunction. Whether to open this can of decisional worms depends on a person’s risk tolerance and how they weigh length versus quality of life.

But there’s a key difference between such decisions and those surrounding some of the vaccines in question. As Simmons, of Mass General, said, “There’s a societal benefit with vaccination against contagious disease.” You are protected by your neighbors’ immunizations and vice versa. Someone with an immune deficiency whose body can’t mount a response to a shot is kept safer by higher vaccination rates. That’s simply not true of a PSA test or a knee-replacement.

Cue the post-Covid tension between public health measures and individual liberties. Parents always have the right not to vaccinate their children. A recommendation does not a mandate make — but the federal guidance on vaccines is often used by states for rule-making, requiring kids to be up to date on their shots to attend public school. To scholars of shared decision-making, the Department of Health and Human Services’ usage appeared to be less about how the doctor-patient conversation takes place, more about delegating the decision about whether a vaccine is advisable to each individual: In other words, nudging questions of public health from the public sphere into the private. They worried that the gray-area connotation that surrounded “shared decision-making” made it inappropriate for government guidance in scenarios where routine vaccination was clearly the standard of care.

It isn’t the first time that federal authorities have used the phrase for vaccines. The expert advisory committee that proposes immunization guidance for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention long used two categories: the vaccines you “should” get and others that you “may” get. In 2019, it changed the terminology of the second category for a few adult vaccines to “shared clinical decision-making.” A commentary in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association described widespread confusion. Some clinicians felt like they’d been left in the lurch, not unlike patients who’ve received an “information-dump” of a consent form with little guidance.

“Historically, ‘shared decision-making’ was used when there wasn’t a clear population benefit, but they wanted to have the vaccine available for people who wanted it,” said Sean O’Leary, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Colorado Anschutz and a committee chair at the American Academy of Pediatrics. “What we saw pretty universally from clinicians is that they hated that kind of recommendation. The response I heard from several folks was: ‘You guys are the experts. If you can’t figure out what the right thing to do is, how are we supposed to do that in a 10-minute office visit?’”

Now, though, years after changing the language that surrounds more ambivalent recommendations, federal authorities have essentially switched some vaccines from “should” to “may.” In some instances, the relationship that they seem to promote between Americans and health professionals is adversarial rather than collaborative. “What I would say to people is: Do your own research,” health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said recently on a conservative podcast. “This idea that you should trust the experts — a good mother doesn’t do that.”

That doesn’t sound like shared decision-making as articulated by the international society convened to study it. Informed consent should already be happening before any immunization. Pediatricians bristle at the idea that they aren’t already having in-depth conversations with vaccine-hesitant parents every day. In the use of “shared decision-making” as a substitute for guidance, rather than a tool to be used in conjunction with it, researchers fear authorities will spread distrust of a helpful technique — and also of the evidence behind these vaccines.