U.S. President Donald Trump’s latest grievance threatening to upend the deeply integrated economic ties between the U.S. and Canada involves business jets.

Trump said on Thursday in a Truth Social post that the U.S. was decertifying Bombardier Global Express business jets and threatened 50 per cent import tariffs on all aircraft made in Canada until the country’s regulator certified four series models produced by U.S. rival Gulfstream.

Trump also said he was “decertifying their Bombardier Global Expresses, and all Aircraft made in Canada” until the Gulfstream planes were certified.

Transport Canada, which is responsible for Canadian certification, did not respond immediately to a request to Reuters for comment.

IAM, a union representing more than 600,000 workers in North America and thousands of workers in the air transportation and aerospace sector, said Trump’s threats “would cause serious disruption to the North American aerospace industry and put thousands of jobs at risk on both sides of the border.”

John Gradek, a lecturer on aviation and supply chain management at McGill University in Montreal, told CBC News he was “flabbergasted” by Trump’s outburst, given the ramifications for the industry.

The price tag for a business jet can run up to $80 million US, and major carriers like Delta and American Airlines have used Bombardier planes in their fleets.

“There’s probably been some misunderstanding about the impact that such a decertification of Canadian aircraft would have on the U.S. domestic air services currently operated by U.S. carriers,” he said.

Here’s what we know so far.

The certification process

Under global aviation rules, the country where an aircraft is designed — the U.S., in Gulfstream’s case — is responsible for primary certification known as a type certificate, vouching for the design’s safety.

Other countries typically validate the decision of the primary regulator, allowing the plane into their airspace, but have the right to refuse or ask for more data.

Following the Boeing 737 MAX crisis — in which two planes made by the Chicago-headquartered company crashed in 2018-2019, killing 346 people, including 18 Canadian citizens — some regulators outside the U.S. delayed endorsement of some American certification decisions and sometimes pressed for further design changes.

Path to decertification unclear

As with many Trump declarations on social media dating back to his first term in 2017, the post has elicited confusion and surprise from some industry players and even parts of his own administration.

It was unclear how Trump would decertify the planes, since that is the job of the Federal Aviation Administration, but he has made similar declarations in the past that were ultimately carried out, often with exemptions, by relevant agencies.

It does not appear the FAA has the legal authority to revoke certifications for planes based on economic reasons, as it can only do so for safety reasons under existing regulations.

WATCH | Concerns over the latest Trump salvo in trade tensions, in aviation:

Aviation analyst ‘flabbergasted’ by Trump’s latest tariff threat

John Gradek, a faculty lecturer on aviation management at McGill University in Montreal, says Trump’s comments hint at a misunderstanding of the plane certification process, as well as how integrated the aviation industry is in North America, even amid the competition between plane manufacturers.

Airline officials said if the U.S. could decertify airplanes for economic reasons, it would give other countries a powerful weapon and could put the entire aviation system at risk.

“Mixing safety issues with politics and grievances is an incredibly bad idea,” said Richard Aboulafia, managing director of U.S. aerospace management consulting firm AeroDynamic Advisory.

A White House official told Reuters that Trump was not suggesting decertifying Canadian-built planes currently in operation. U.S. airline officials told Reuters that FAA officials had made similar statements.

The FAA declined immediate comment to Reuters, and to the New York Times the agency directed media queries back to the White House.

Bombardier

Montreal-based Bombardier said it had taken note of Trump’s post on social media and was in contact with the Canadian government.

“Thousands of private and civilian jets built in Canada fly in the U.S. every day. We hope this is quickly resolved to avoid a significant impact to air traffic and the flying public,” the company said through a spokesperson.

The statement added that Bombardier’s aircraft, facilities and personnel were fully certified under FAA standards.

WATCH | U.S. Treasury secretary comments amid U.S.-Canada trade tensions:

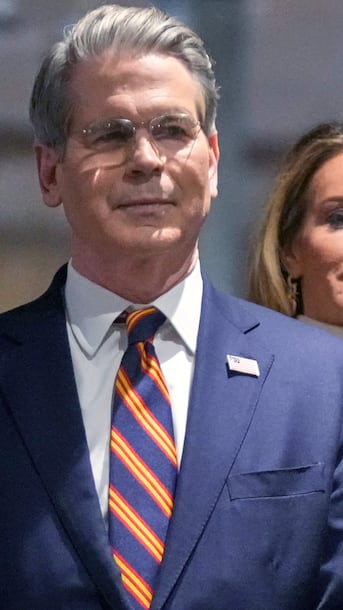

Scott Bessent warns Carney not to ‘pick a fight’ with Trump

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s latest challenge to Prime Minister Mark Carney comes on the heels of claiming Carney walked back his headline-grabbing speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, while on a call with U.S. President Donald Trump. The spat looms over CUSMA renegotiations as the deal comes up for review later this year.

Data provider Cirium said there were 150 Global Express aircraft in service registered in the U.S., operated by 115 operators and 5,425 total aircraft of various types made in Canada in service registered in the U.S. including narrowbodies, regional jets and helicopters.

Bombardier operates multiple service centres in the United States, recently announcing such a facility for Fort Wayne, Ind., and it has operations in Wichita, Kan., where it is growing its defence business. It has been estimated that Bombardier has 2,500 to 3,000 employees based in the U.S.

The FAA in December certified Bombardier’s Global 8000 business jet, the world’s fastest civilian plane since the Concorde with a top speed of Mach 0.95, or about 729 mph (1,173 kph). It was initially certified by Transport Canada on Nov. 5.

It was unclear what planes beyond Bombardier’s Global large-cabin jets would fall under Trump’s increased tariffs, including the Airbus A220 commercial jet.

The A220 was developed by Bombardier Inc. at a cost of more than $6 billion US, with the Quebec government investing in the program. Bombardier reached an agreement with Airbus in 2018 that saw it hand over control of production for a fee.

The plane is built in Mirabel, Que., and Mobile, Ala.

Gulfstream

In his post, Trump said that Canada “has wrongfully, illegally and steadfastly refused to certify the Gulfstream 500, 600, 700 and 800 jets, one of the greatest, most technologically advanced airplanes ever made.”

Setting aside Trump’s heated language, it is true that Transport Canada has yet to fully certify those models from Gulfstream, a subsidiary of General Dynamics in Reston, Va.

A Gulfstream G600 is presented at the Paris Air Show on June 18, 2025. (Thibault Camus/The Associated Press)

A Gulfstream G600 is presented at the Paris Air Show on June 18, 2025. (Thibault Camus/The Associated Press)

The following are the dates that General Dynamics noted FAA certifications had taken place for the models in question:

Guflstream G500: July 20, 2018.Gulfstream G600: Aug 1, 2019.Gulfstream G700: March 29, 2024.Gulfstream G800: April 16, 2025.

The European Union Aviation Safety Agency, meanwhile, certified the Gulfstream G800 shortly after the FAA approval.

Gradek told CBC News that the Canadian certification process is “world-class” and “exemplary.”