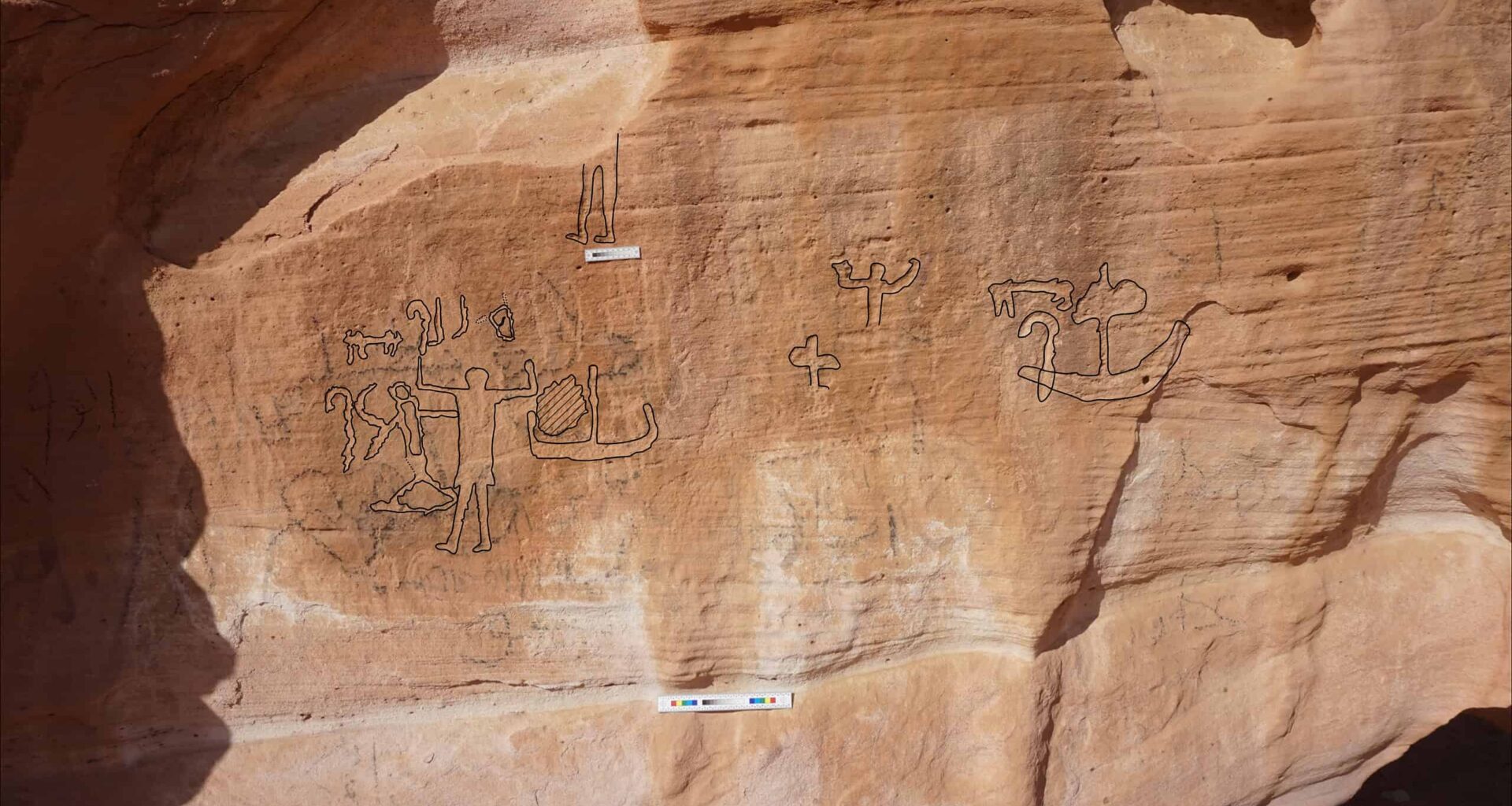

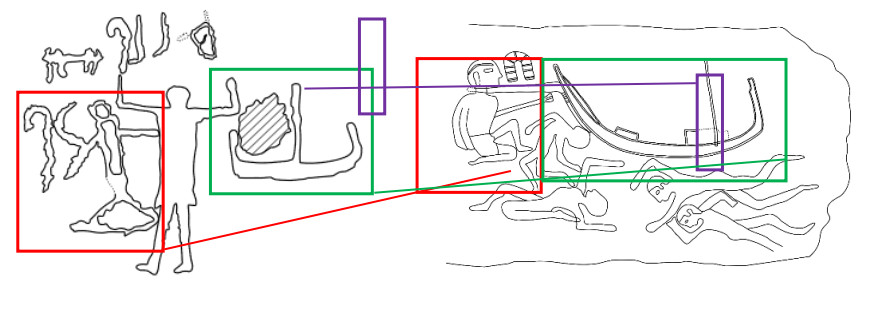

Victorious man strides forward with raised arms; at left, a bound kneeling figure pierced by an arrow. An Egyptian boat signifies dominance. Inscription reads: God Min, ruler of copper region. Credit: M. Nour El-Din/redrawing: E. Kiesel.

Victorious man strides forward with raised arms; at left, a bound kneeling figure pierced by an arrow. An Egyptian boat signifies dominance. Inscription reads: God Min, ruler of copper region. Credit: M. Nour El-Din/redrawing: E. Kiesel.

Five thousand years ago, the silence of the Sinai desert was broken by the sound of stone striking stone. In a remote dry riverbed known as Wadi Khamila, an artist (or perhaps a soldier) carved a terrifying scene into a sandstone cliff.

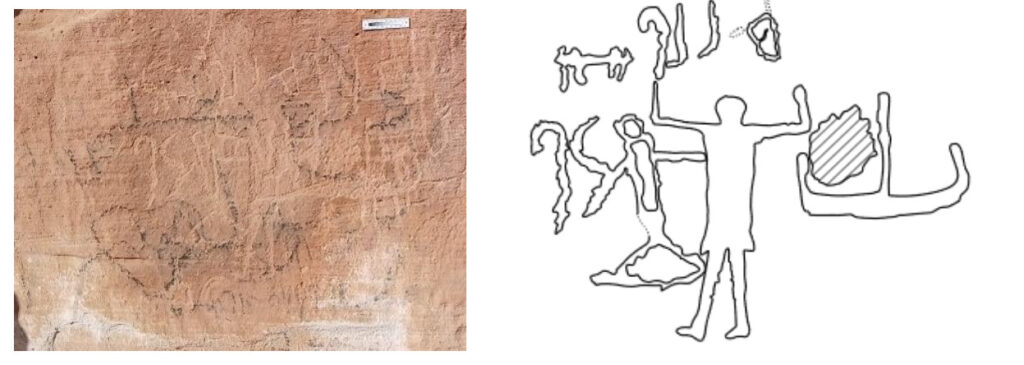

The image is stark: a towering man stands with his arms raised in a “jubilating” V-shape, a gesture of absolute triumph. Before him kneels a smaller figure, arms bound behind his back, an arrow protruding from his chest. It’s a snapshot of one of the earliest colonial conquests in human history.

For millennia, this brutal tableau remained hidden in the heat and dust of the southwest Sinai, approximately 35 kilometers east of the Gulf of Suez. Now, a new survey by archaeologist Mustafa Nour El-Din and Egyptologist Ludwig Morenz has brought it to light, offering a rare and chilling glimpse into the violent origins of the Pharaonic state.

A Terrifying Manner of Dominance

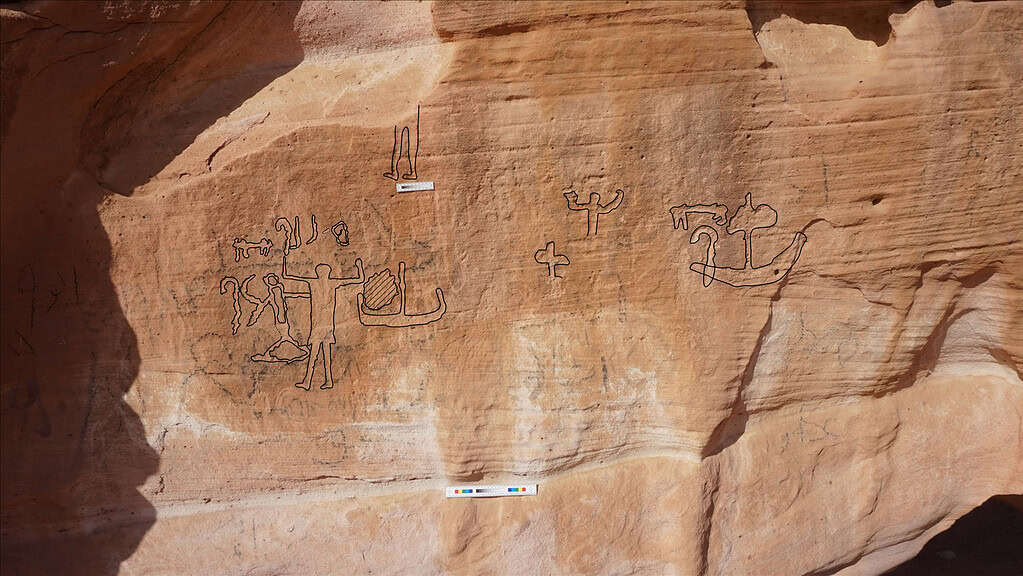

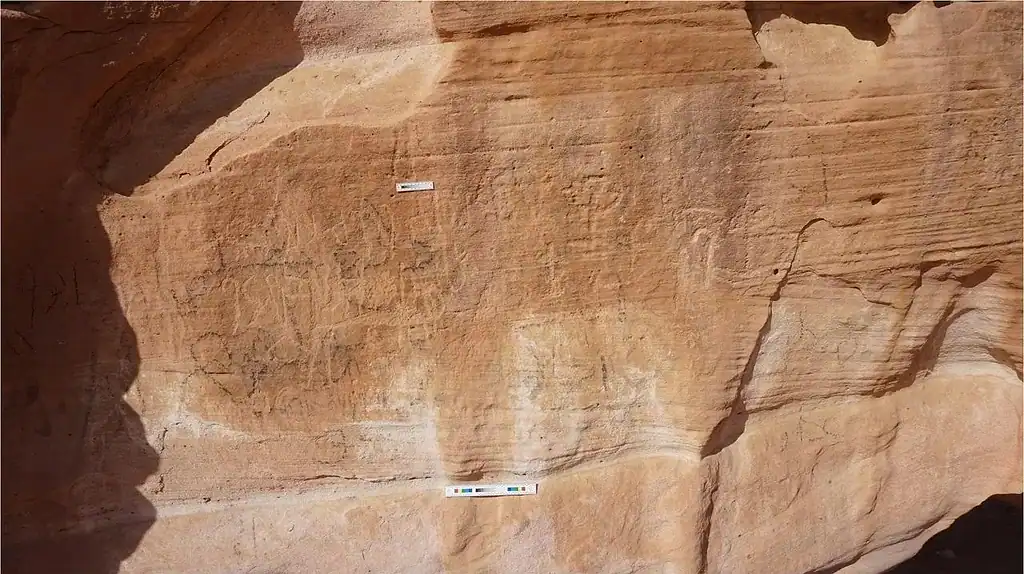

The 5,000-year-old inscription in Wadi Khamila, shown without tracing. Credit: M. Nour El-Din

The 5,000-year-old inscription in Wadi Khamila, shown without tracing. Credit: M. Nour El-Din

The discovery began with a survey in early 2025 by Mustafa Nour El-Din of the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. While Wadi Khamila was previously known for Nabataean inscriptions dating to a much later era, El-Din spotted something far older on a prominent rock panel.

The scene he found “shows in a terrifying manner how the Egyptians colonized the Sinai and subjugated the inhabitants,” according to a statement by the research team.

The composition is visually dominated by the striding, triumphant man. He wears a simple loincloth and no headgear, yet his posture speaks authority. The figure kneeling before him represents the local Sinai population — nomadic groups who, at the time, lacked the centralized government or writing systems of their powerful neighbor to the west.

This specific iconography of subjugation — a bound captive struck by a weapon — has deep roots in Egyptian state ideology. It parallels famous early dynastic scenes like those at Gebel Sheikh Suleiman, where pharaonic power was brutally advertised to the Nubians in the south.

Here in the Sinai, the message was identical: resist, and you will be crushed.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

The researchers note that this rock panel “certainly represents one of the earliest depictions of dominance in another territory”. It suggests that the unification of Egypt didn’t just happen along the Nile; it was forged through the violent extraction of resources from its periphery.

Central scene of Egyptian dominance, Wadi Khamila

Central scene of Egyptian dominance, Wadi Khamila

The God of the Copper Mines

What drove the Egyptians to march across the burning sands of the Sinai? It wasn’t just a desire for land. It was a hunger for “mineral resources, especially copper and turquoise,” according to the archaeologists.

The inscription found alongside the violent imagery provides the “religious justification” for this resource grab. Though weathered and difficult to decipher, the hieroglyphs appear to identify the patron of this expedition.

“The inscription is likely to announce Egyptian dominance under the patronage of Min,” explains Professor Ludwig Morenz of the University of Bonn.

The text reads: Mnw ḥq3 bj3w. Translated, it means: “God Min, ruler of copper ore / the mining region”.

This is a crucial detail. In the Proto- and Early Dynastic periods, the god Min was not only the deity for fertility, reproduction, and male sexual potency; he was the “divine protector of the Egyptians in areas beyond the Nile Valley.” He was the god of the dangerous frontier, the patron saint of prospectors and conquerors. By carving Min’s name and title into the rock, the Egyptians were “sacralizing” the landscape, claiming the copper-rich earth of the Sinai as the property of their gods and their king.

Min is famously depicted as ithyphallic (with an erect phallus) and holding a flail. While later interpretations focused on agricultural fertility, in this early “colonial” context, his image represented the raw, masculine potency of the pharaoh. By carving Min into the rocks of Wadi Khamila, the Egyptians were projecting a message of aggressive generation and dominance — essentially saying, “The King’s power extends this far.”

As Morenz and Nour El-Din write, this transforms the rock panel into a kind of “visual propaganda,” asserting an Egyptian cultural identity in a “socio-cultural periphery.”

As the Egyptian state settled into the stable Old Kingdom, its administration became more specialized. They didn’t just need a god of “power”; they needed a god of the border. Enter Sopdu. Sopdu’s name (written with a sharp triangle or thorn) translates to “The Sharp One” or “Sharp of Teeth”. Unlike Min, who was a general god of the desert, Sopdu was specifically the “Lord of the East” (Neb Iabet).

A Palimpsest of Power

One of the most intriguing aspects of the Wadi Khamila panel is what is missing.

Behind the triumphant figure floats the outline of a boat. In ancient Egyptian iconography, the boat was a potent symbol of the ruler — it represented the state’s ability to project power and transport heavy resources across vast distances.

However, the specific identity of the king who commissioned this violence remains a mystery. The researchers noticed that “a presumed name inscription above the boat has been (deliberately) erased.”

History is often a palimpsest; a manuscript written over again and again. This rock face is no exception. The 5,000-year-old scene was not treated with reverence by later visitors. The panel features “multiple overwritings,” including much later Nabataean scripts and black Arabic graffiti.

This layering of history shows that while the specific political claim of that early pharaoh may have been erased or forgotten, the location remained a vital waypoint for travelers. The “prominent location in the landscape” and the “smooth surface” of the rock invited generation after generation to leave their mark.

The Dawn of “Paleocolonialism”

Subdued and killed man in Wadi Khamila, contemporary parallel from Gebel Sheikh Suleiman. Drawings by E. Kiesel.

Subdued and killed man in Wadi Khamila, contemporary parallel from Gebel Sheikh Suleiman. Drawings by E. Kiesel.

This discovery fundamentally shifts our understanding of the region. “Until now, Wadi Khamila has only been mentioned in research in connection with Nabataean inscriptions that are around 3,000 years younger,” says Morenz.

The presence of this panel proves that the Egyptian state’s “colonial network” was far more extensive than previously thought. It links Wadi Khamila with other known sites of Egyptian imperialism in the Sinai, such as Wadi Ameyra and Wadi Maghara.

The researchers describe this as “paleocolonialism” — an early form of imperialism where the motivation was “not simply an abstract expansion of territory,” but a targeted effort to secure the raw materials necessary for the growing Egyptian state.

The violence depicted in the rock art served as a propaganda tool to terrorize the local nomadic population and secure the supply lines for the copper that would forge Egyptian tools and weapons. As the study authors conclude, this rock picture announces “the Egyptians’ colonial claim 5,000 years ago”.

The team plans to return to the desert. “Research has just begun,” they write, “and we are planning for a first bigger campaign” to find more evidence of this ancient struggle for the Sinai.

The findings were reported in the journal Blätter Abrahams.