The relatively modest Atlantic hurricane season to date may soon kick into high gear. Long-range outlooks from multiple models are in unusual agreement on the chance of a powerful hurricane moving toward North America in the one- to two-week window. That’s way too far out for any definitive forecasts in terms of location, strength, or timing – or whether this system would reach North America at all – but there’s still reason to believe the models may be on to something, as there’s an emerging window of alignment for several storm-boosting modes of the North Atlantic ocean and atmosphere.

Ahead of that potential threat, there’s a slim chance of development for a tropical spin-up this weekend off the Southeast U.S. coast, and higher odds of a named storm developing in the central Atlantic next week. As for former Tropical Storm Dexter, declared post-tropical on Thursday, it was spinning harmlessly across the remote North Atlantic as a powerful mid-latitude cyclone. Dexter successfully avoided any land areas during its 3.5-day run as a weak-to-moderate tropical storm.

The system off the Southeast coast is just south of a weak frontal system arcing southward and westward from ex-Dexter. As of midday Friday, this low had widespread but disorganized showers and thunderstorms (convection) associated with it. By later in the weekend, the system will move northward into the frontal zone and will experience higher wind shear, so any development is expected to be short-lived. In its 2 p.m. Friday Tropical Weather Outlook, the National Hurricane Center gave this system only a 10% chance of development over the next two days.

In the central tropical Atlantic, toward the north side of the Main Development Region, a disturbance named 96L had a well-defined spin on Friday but was bereft of much convection. Wind shear will remain light to moderate over the next few days, and sea surface temperatures along the path of 96L will reach 29 degrees Celsius (84 degrees Fahrenheit) by next week, both of which favor development. Working against 96L will be a dry mid-level atmosphere, with relative humidity predicted to drop from around 60% on Friday to below 50% by Monday.

Support for 96L among European and GFS ensemble models has been sagging over time, and only a few ensemble members now project development of 96L. Whether or not it develops into a tropical cyclone, 96L is expected to angle northwest well before threatening the Caribbean and will likely recurve into the remote central Atlantic next week. In its 2 p.m. Friday Tropical Weather Outlook, the National Hurricane Center gave this system a near-zero chance of development in the two-day period and a 40% chance for the seven-day period, down slightly from earlier outlooks.

A system worth watching in the 1- to 2-week period

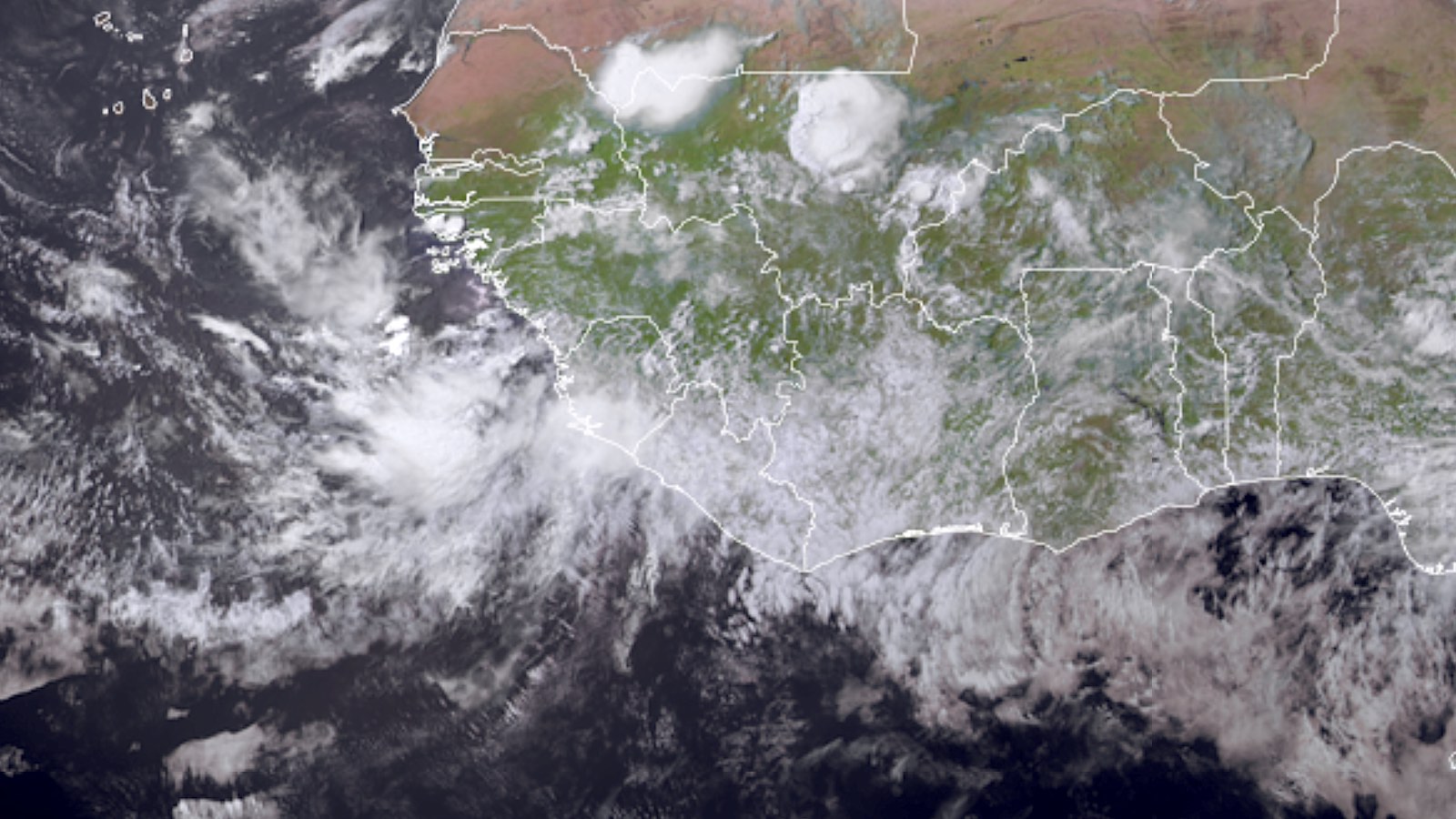

Multiple model ensembles have become increasingly insistent that a substantial hurricane could eventually develop from a strong disturbance moving from western Africa into the far eastern tropical Atlantic this weekend. Over the next week, several factors that enhance development in the Atlantic will be in place as the tropical wave approaches. These include:

A pulse of the Madden-Julian Oscillation. This semi-cyclic feature sends large areas of rising motion and convection slowly eastward along the equatorial zone, circumnavigating the globe every 30 to 50 days. MJO pulses can vary greatly in timing and strength.

A convectively coupled Kelvin wave. CCKWs are huge impulses, spanning thousands of miles, that move from west to east through the stratosphere, typically rolling along at about 30 to 40 mph. CCKWs are centered on the equator, with their effects progressively weaker as you move toward the subtropics.

Unusually warm sea surface temperatures. SSTs have been warmer than average for early August throughout the Northern Hemisphere subtropics in recent weeks, and now they’re increasing over the tropics as well. Charts from the University of Arizona show that the Main Development Region of the tropical Atlantic (between the Lesser Antilles and Africa) is up to 1 degree Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than average for the date. Readings are also close to 1°C (2°F) warmer than the seasonal average farther northwest toward the Bahamas.

Rarely do things line up as favorably for tropical development subseasonally as they will next week in the East Atlantic

Hard to get the MJO, a CCKW, & an Eq Rossby Wave this strong to all line up at once

This will be a good litmus test of how favorable the Atlantic is this yr pic.twitter.com/KiqLSgEPqY

— Eric Webb (@webberweather) August 7, 2025

By the middle of next week (around Wednesday, August 13), this tropical wave will be in the central tropical Atlantic, and we’ll have a better idea of how the longer-range steering currents and other atmospheric features are stacking up. If the system does end up approaching the U.S. East Coast – a possibility suggested by long-range ensemble modeling from the Euro, GFS, and a new Google AI model – it would most likely be during the week of August 18-22. There’s always the possibility any hurricane could recurve well before reaching the East Coast, so now is the time to watch and wait – and to avoid fixating on any specific model forecast (an unfortunate problem right now in the world of “social mediarology”), which was phrased perfectly by meteorologist Michael Lowry:

We’re still 4 or 5 days out before any realistic chance of something even forming. A tiny deviation on when or where a system forms this far out – imperceptible details we have no way of determining today – can have enormous implications on where it tracks or how strong it gets in two weeks. It’s an exercise in futility to get mired in the details of a 10-plus day model forecast. It’s truly anyone’s guess.

In today’s newsletter, it’s all about the tropical wave that isn’t even in the National Hurricane Center’s outlook yet. It’s the feature social media is a flutter over because of dubious 2-week forecasts. I explain what we know about it and what we don’t. ⬇️

— Michael Lowry (@michaelrlowry.bsky.social) 2025-08-08T13:52:37.458Z

Across the Atlantic so far this season, it’s been (mostly) crickets

Rarely if ever has a tropical season in the Atlantic started off with so many named storms with so little collective power. The season’s four tropical storms to date have all fallen short of hurricane strength, and three of the four actually developed outside the tropics, north of 30 degrees north latitude. The most destructive of the bunch by far has been Chantal, which led to deadly flooding in early July well inland across central North Carolina. Six lives were lost, and dozens of roads remain washed out.

As of August 8, statistics kept by Colorado State University show that the Atlantic season’s accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) sat at 3.7 units — a small fraction of the average value to date of 12.1. The three other storm-generating ocean basins north of the equator (Northeast Pacific, Northwest Pacific, and North Indian) are also running below average for ACE, making for an unusually quiet start to the Northern Hemisphere: the hemisphere’s total ACE of 84.6 is far behind the average year-to-date value of 161.3.

Interestingly, the number of named storms in the four basins, 27, is actually above the average to date of 22, and the number of hurricane-strength storms, 10, is just below the average to date of 11. What stands out is the brevity of those hurricane-strength storms. There have been only 10.5 “hurricane days” north of the equator through August 8, compared to the average to date of 33.2.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.