Noam: Hey, I’m Noam Weissman and you’re listening to Unpacking Israeli History, the podcast that takes a deep dive into some of the most intense, historically fascinating, and often misunderstood events and stories linked to Israeli history. This episode of Unpacking Israeli History is sponsored by Andrea and Larry Gil.

If you’re interested in sponsoring an episode of Unpacking Israeli History or just saying, what’s up, be in touch at noam@unpacked.media.

That’s noam@unpacked.media. Okay, cool.

Before we start one more thing, we’re on Instagram, we’re on YouTube, on TikTok, just search Unpacking Israeli History and hit the follow or subscribe button. Okay, yalla, let’s do this.

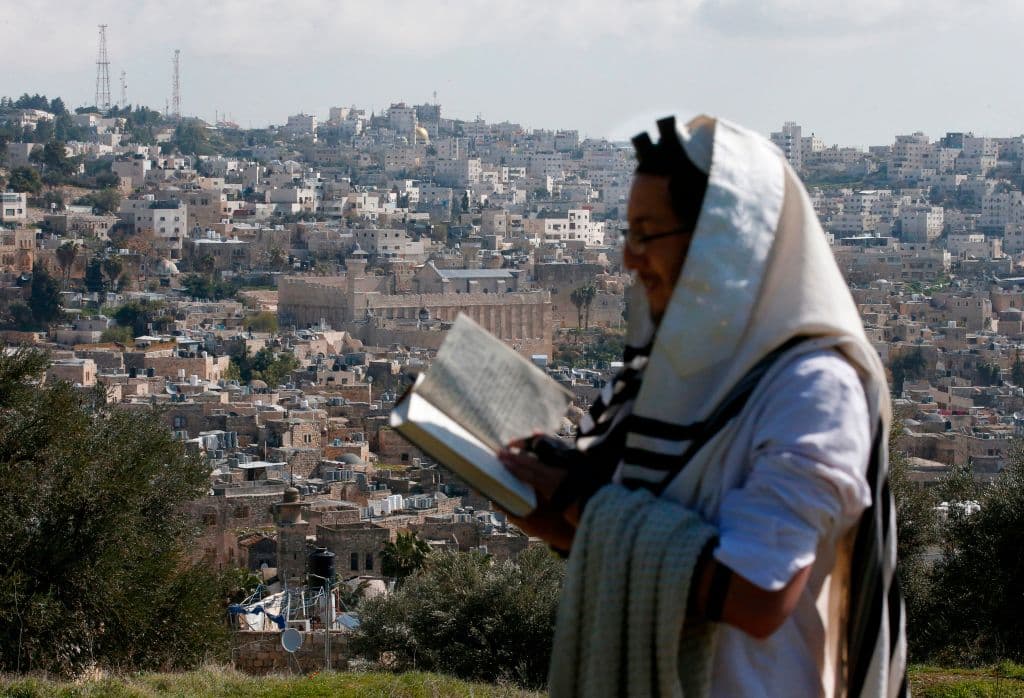

I don’t think I have to tell any of our listeners or viewers about the difficult topic, the painful topic, of Palestinian terrorism. Palestinian terror attacks in the West Bank and elsewhere have taken thousands of innocent lives, women, children, families targeted in their homes, on the roads and in their beds.

But in recent years, there has been a different, disturbing trend that has emerged. It’s a small but dangerous fringe that targets Palestinian civilians and their property. They’re Jewish extremists whom many Israelis see as vigilantes and who many Palestinians see as carrying out acts of terror.

Haviv Retig Gur is here with me to have this conversation about this topic. Haviv, I am so happy to have you on this podcast.

Haviv: Noam, it’s really good to be back. Thanks for having me.

Noam: It’s always awesome having you and let me read for you, Haviv, a letter that we got from a listener named Aryeh. So he writes:

Hi, Noam.

What’s up, Aryeh?

I’ve been seeing a lot of videos on X about violence between Jewish settlers and Palestinians in Judea and Samaria. What’s the background to the stories? Is there more context to the videos than just a bunch of wild teenagers beating up on Arabs? Why isn’t the army taking more control of the situation? Can you dedicate some time to the ongoing tensions?

So, Haviv, you probably would not be so surprised to hear this, but maybe some people watching or listening are. We didn’t get this email in the last few weeks, though we have gotten many letters like this recently. This came in March, five months ago at the time of this recording. This isn’t a new phenomenon, though for many, it’s something that people are talking about now more than ever.

So, Haviv. I want to have a conversation about this topic about settler violence as it’s called. And I’ve been thinking about it obsessively. I know you have a lot of thoughts on it, but I want to talk about it in a way that’s kind of with broader strokes, with some texture, with some care. Is that cool? Can we do that?

Haviv: Yeah, let’s do it. I think that’s very valuable, getting the larger context, the effects, the causes.

Noam: Okay, so before we get to that, before we get to the settler violence, I want to like do some definitions with you. What is a settler?

Haviv: A settler is a term often applied pejoratively, I would even say usually applied pejoratively in English. That’s the connotation. For an Israeli, in this context, the word means many things. There are board games.

Noam: Settlers of Catan.

Haviv: For example. But in this particular case, it’s a reference to Israelis living over the Green Line. Israelis living over the ceasefire line of 1949 that ended the 48 War, which was either the West Bank or Gaza territory controlled by, in Gaza’s case Egypt and in the West Bank’s case Jordan. That’s why it’s called the West Bank. it is on the West Bank of the river. The rest of Jordan is the East Bank. It is the Jordanian name for the territory during this conquest, during the Jordanian holding of the territory between 48 and 67.

Jordan annexed it. I mean Palestinians born there in those years of Jordanian birth certificates and the Jordanians also went out of their way to exercise control, claim control, and by the way demolish everything Jewish they could lay their hands on. I mean, including very nearly the entire Jewish quarter, the old city of Jerusalem.

And then in ’67, in a war on all fronts, essentially, Israel conquers both the West Bank and Gaza, one from Jordan, the second from Egypt, and now finds itself in control. And we have some data, some historical evidence, conquering the West Bank or in Hebrew Judea and Samaria was not a goal of the war. To the point where you had a debate back in, I think, February 49, already in that 48 war, where Yigal Allon, one of the great generals of that war, came to the Israeli cabinet and he said, I can take the West Bank in, I think he said, five days. This is something that Benny Morris, the historian that we both know, has written about. And if I’m not mistaken, it was the interior minister of the cabinet at the time, the provisional government of the brand new state of Israel, raised his hand and said, I’m sorry, but what are we going to do with all the Palestinians living there if we conquer it? Right?

Noam: Mmm.

Haviv: And 10 minutes after the 67 war, really, I think within three weeks, that same Yigal Allon comes to the Israeli cabinet and he says, we’ve now taken the West Bank. He was told not to back in 48, in 49 and he’s no longer a general, he’s no longer even in the cabinet, but he’s still a very significant figure and strategic thinker and public intellectual. And he comes to the cabinet and he says he offers the first version of what he calls the Allon Plan.

And the basic idea is Israel cannot control the Palestinian population. That’s unethical, it’s immoral, it’s also just logistically impossible, it’s over the long term a disaster. And so, let’s divide the West Bank based on our needs and based on their needs. Which is to say, all the major Palestinian population centers in these gigantic blocks that are roughly, I don’t know, 60% of the West Bank, 40% of the West Bank, there many different versions of the Allon Plan, but the basic theory is they form their own state (or maybe join Jordan somehow), and the rest is Israeli.

Now, what is ‘the rest is Israeli’?

Allon believed that Israel needs to push up from the coastal plain, you have the Mediterranean, then you have a nine mile wide strip at its narrowest of Israeli towns and cities along the coast, and then the highlands begin that are the West Bank, Judea and Samaria. And the last thing Allon said was, we need to control the strip of land along the river that prevents us from shrinking down to the point where we can’t defend ourselves from the highlands against, let’s say, an Iraqi tank invasion.

Long story short, Israel finds itself since 67 in control of territories and automatically, immediately is having these complex debates about what to do about it.

And we find the beginning of the first settlements almost perfectly along the Allon Plan. The very first settlements are left-wing settlements along the Jordan Valley, tiny little villages that are meant to be kind of military control spots that to this day vote left some of them because they were founded by left-wing governments back in the day. Most settlers to this day live within, I don’t know, 2,000 feet, maybe up to two miles from the Green Line on the other side around Jerusalem, just east of Tel Aviv. That’s the vast majority, maybe 75% of settlers, and that’s about pushing up slightly to the mountain range for security.

And so what is a settler? A settler is, at first, a kind of military deployment and an attempt to take land that makes Israel safe.

And then beginning in 67, you also have, a religious Zionist movement that says something completely different. It’s not the secular socialist left governments thinking how do we protect our territory against a future invasion, which is a perfectly reasonable thing to ask in 1967. It’s people who say the worst century of Jewish history also has become the great century of Jewish history in which the Jews all returned to the land. All of this is prophecy. We are in a messianic age and the coming of the Jews to their homeland is the heart of our story and the heart of the story of the world.

And the biblical homeland is kind of the West Bank. We’ve talked about this before. What part of the Bible happens in Tel Aviv? All the Bible happens in the West Bank. And so they begin a settlement movement that is not adjacent to the Green Line or along the river. They begin a settlement movement that sets up small spots in between Palestinian population centers. And the purpose of it is to head off a future Palestinian state on some kind of a long plan model. So there are many different settlement movements and the word is used by many different groups and many different people within Israeli politics but also overseas in many different ways.

Noam: When you say settler, in Hebrew do you say mitnechel? Is that the word you use?

Haviv: Mitnechel is the left wing, which almost means squatter, is the left’s pejorative version of settler in Hebrew. And what they themselves call themselves is mityashiv. Mityashiv is someone who settles, but in a neutral sense of the word, just literally you might someday pack up from, you live in Florida, and settle in Arizona in that sense.

Noam: That’s what I wanted to get to a little bit, understanding and talking through the aspect of what’s pejorative, what’s not pejorative, understanding the history from 67 to today. And I want to go through a little bit of that history. And you touched on all of this. It’s important for everyone to remember that not until 67 was there any settler movement, and even that movement took a while to develop. There was this from 67 to 73, the settler movement was mostly military. It was strategic. It was not religious in nature. There were very few people that actually were moving to the area of Judea and Samaria or the West Bank.

And actually, it wasn’t until Gush Emunim, this movement that you were talking about before, this religious Zionist movement took shape, in the mid 70s, around 74, that the settler movement really started. There was only a few thousand people living over the Green Line.

And then in 1980s, it was closer to 15,000 and growing in the 1990s, it got to around 100,000. 2000, in the year 2000, it got to around 200,000. 2010 to 320,000. 2020 to 2025, we’re now at around 500,000 plus Jewish people living in the area known as Judea and Samaria and living in the West Bank.

So I think that that’s important to talk about the trajectory of what took place. Now what I find interesting always, one of the things that really spurred the moments, historical moments that spurred the settler movement was actually something that happened outside of Israel, which was when the United Nations declared in 1975 in UN resolution 3379 that Zionism is racism.

And when they declared that, it was the Labor government that was the leadership at the time, I believe. And they were the ones that said, OK, you want to you want to call the whole project racist? Well, you know what we’re going to do? We’re going to triple down and quadruple down and we’re going to allow people, whether de jure or de facto, to build in this this area. And so that’s that’s something that took place.

But there was something else that took place and that’s the religious fervor. There was a religious fervor, the religious Zionist worldview, I think was under wraps in many ways, because there were two different styles of religious Zionism.

Style number one of religious Zionism was more proper, was more moderate, was more bourgeois even in many ways. It was less romantic. It always went actually more with the left than with the right in the political echelon.

But Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook, who is the son of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, he said a few weeks before the Six-Day War, it’s almost prescient in a way that’s hard to imagine, he said:

19 years ago on the night when news of the United Nations decision in favor of the resurrection of the state of Israel reached us, when the people streamed into the streets to celebrate and rejoice, I could not go out and join in the jubilation. I sat alone in silent. A burden lay upon me. During those first hours, I could not resign myself to what had been done. I could not accept the fact that indeed they have divided my land.

And then he says this line:

Where is our Hebron? Have we forgotten her? Where is our Shechem, our Jericho? Where have we forgotten them? What about all the land beyond the Jordan, each and every plot of earth, every region, hill, valley, every plot of land that is part of the land of Israel. Have we the right to give up even one grain of the land of God? On that night, 19 years ago, I sat trembling in every limb of my body, wounded, cut, torn to pieces, I could not rejoice.

So part of the religious Zionist worldview, which developed with the Gush Emunim project in the mid 70s, was this belief that the Judean land, Judea and Samaria, is the most Jewish land of all. And therefore it is not, you don’t settle your own land, goes this argument, you develop your land. There’s nothing more Jewish than the areas of Judea and Samaria.

And yet, and yet, there’s another people living there. Those are the Palestinian people. And what happened in the mid 90s was an agreement called Oslo Two, in which there was a decision was made that the West Bank would be divided up into three categories, areas A, B and C. Area A, which is around 18%, is administered by the PA. Area B, which is around 22% is administered by the PA, shared security control with Israel. And Area C is administered by Israel. And that’s 60% of the land.

Haviv, are the people who are described as settlers, are they living in primarily area C or are they also in areas A and B? And before we get to settler violence, we’ll get there, we’ll get there folks. But before we get there, where are these people living? Are they living in area C? They’re not in area A, right? So where are they? And what are the different types of communities that settlers, because that’s the term that is used, that settlers live in?

Haviv: 100% of the Israeli settlers live in area C, in the 60% of the West Bank you described under full Israeli control. 100% of the settlers, and I have to look up the exact number, people can look it up, I believe something like a quarter million Palestinians, out of the several million, there’s incidentally a bit of a debate between the Israelis and the Palestinians, or how many Palestinians, it’s millions according to everybody.

Noam: It’s two to three million that Palestinians live in the West Bank.

Haviv: Right, is it two and a half or is three and a half? Right, right. But the basic point is that all the Israelis, depending on where you draw the West Bank, Israel claims East Jerusalem and it also claims the Old City of Jerusalem, which European Union diplomats insist is not Jewish, even the Jewish quarter of Jerusalem. So it’s contentious, is my point.

But give or take 450 to 550,000 people. That is a much, much larger number than the numbers you read out, obviously, which are the slow growth. It really was a very slow growth. And it was also a growth almost entirely concentrated in places that are very easy to exchange. For example, one of the Palestinian complaints during the Oslo years was that settlements grew from 100,000 settlers to something like 140,000 settlers, something like that. 150,000 even, over the course of 92 to 99 roughly.

But a huge amount of that growth was two settlements out of 100. And those two settlements were new settlements and they were called Modiin Elit and Beittar Elit and they’re c. They’re cities built for the Ultra-Orthodox community. Both of them are within 2000 feet of the green line. They are just northwest of Jerusalem and southwest of Jerusalem. And they are very, close to the green line.

Noam: And the reason you’re saying it’s close to the green line and why that matters is because your point is that it’s not encroaching on Palestinians who are living there. Like, what’s the point of mentioning that it’s close to the green line?

Haviv: Yeah, in other words, again, in the Israeli perspective, okay, if within 2000 feet of the green line you have two cities that are a quarter of all settlers, then a quarter of all settlers is solvable by the exchange of a few square miles. And so that’s not the problem. In other words, that doesn’t count in the Israeli mind.

Now, by the way, in Palestinian discourse, honest Palestinian discourse, okay, if you support Hamas, none of this is at all relevant, the Jews should all be killed and expelled. But there are Palestinians who are willing and believe that they have to come to a compromise with the Israelis. The Israelis aren’t going anywhere. The Palestinians aren’t going anywhere. And they support two states. And they are very frustrated at settlements.

And they look at that. They say, even if it’s in places that I just described as easily exchangeable, it nevertheless is a signal of Israeli intentions. And so they see it as undermining the credibility of any Israeli who then comes to them and says, hey, we’re still interested in peace in some way.

After October 7, there are very few Israelis or Palestinians who cross the aisle and say that to each other. But there used to be quite a lot. And maybe someday there’ll be a lot again. So it’s seen as a signal of Israeli intent, even if the Israelis are like, what are you complaining about, as I just did, right? What are you complaining about? It’s really easy to exchange that little plot.

But that’s a huge number of settlers. There are somewhere between 110 and 140 settlements that are recognized by the state of Israel. And the reason I say somewhere between is just a municipal thing. Whatever, give or take 130 settlements.

And there are another at least hundred and possibly double that wildcat outposts that are, even under Israeli understanding, illegal, and set up on hilltop somewhere and possibly in places encroaching on areas B and A and possibly in places and there have been famous court cases on this over the years, encroaching on private Palestinian property, which is also a contested question because it’s village property, not personal property sometimes according to a land registrar, the Jordanian occupation. There’s no order, there’s no clarity, there’s no legal clarity. And so a lot of these things are very complex.

Incidentally, if you’re Palestinian, the fact that the West Bank is run out of a military administration as a Wild West with no clear land registrar, chaos favors the strong. So that’s how Palestinians view that.

Long story short, you have the security-minded slash just literally housing settlements. They’re just suburbs. There are little towns across the green line that are 20-minute drive from Tel Aviv, obviously without morning traffic, that are just high-tech people who vote left, even. And it’s just the only affordable place for them to live, close drive into their high-tech job. There’s a lot of that. I count the Haredi cities as part of that because it’s a housing settlement. People who live there don’t think of themselves necessarily as Zionist. Some of them, very classic Ashkenazi, Haredi, non-Zionist kinds of ultra-orthodoxy. So you have those security slash housing communities. They are most settlers.

Then you have one other thing which is important. And I think Modiin Illit and Beitar Illit are also part of it, which is the ring around Jerusalem. So you have these towns around Jerusalem that many of were incorporated into Jerusalem municipally. So Ramot, Gilo, Neve Yaakov.

I have to say, my dad was a parliamentary aide to a Meretz member of Knesset in the 1970s as a young law student, that is very left-wing. In other words, that’s basically the sort of progressive left edge of the Israeli political spectrum. My dad supported a Palestinian state before it was cool, you know, on the left in the 90s. And we nevertheless lived in Neve Yaakov when I was born and we lived in Gilo, I think in around second grade. And these are over the green line.

Noam: Wow, wow. Yeah, my parents lived in Gilo also. and they also voted, they’re the type of people that would vote on the left also.

Haviv: It feels like a Jerusalem suburb. It’s hard to live in Jerusalem. It’s expensive to live in Jerusalem. My mom was an archaeologist working in a museum in Jerusalem. My dad was a prosecutor in the police. So they had to live in Jerusalem. They couldn’t just move to some cheaper place. And these are suburbs where you could just hunker down.

And long story short, those are settlements. And Neve Yaakov, by the way, today, mostly Haredi, back then mostly working class, that’s in northern Jerusalem, Gilo is in southern Jerusalem. So that ring around Jerusalem was built by governments purposefully to protect Jerusalem, access to Jerusalem, control of Jerusalem, and the safety of Jerusalem in a future war.

And then, as I said before, you have the third movement. There’s the Jerusalem, there’s the holding on to the mountain slash just having housing for people. And then there, because it’s a narrow coastal strip with which, which is the most, most of the population density of the country. And then you have the ideological religious Zionist movement. Now there’s overlap. Okay. There’s high tech engineers who live in the West bank to be close to their work and also believe that they are part of this redemptive story. The Jewish people returning to their biblical heartland. So it’s not that people can’t be both, but If you come to somebody who grew up in Gilo like myself and say to them, how dare you be a settler? They’re going to blink at you three times and not know what you’re talking about. That’s not what it’s about.

Noam: Meaning it’s not about an ideological messianic movement for some people and it is for obviously other people who are in the settler movement.

Haviv: Right, but the smaller towns and villages, Israeli towns and villages in Area C throughout the central watershed of the West Bank, that’s absolutely what it’s about. And those are the distinctions.

Noam: Do that’s what I want to get into now. The topic of settler violence. I find that this is a topic that paralyzes people, that people have no ability to talk through. It’s become so difficult to talk about a topic like this because so many people out there in the world just demonize Israel no matter what. They will look at anything that Israel does and say, see, they’re just trying to colonialize, to be imperialist, to take over the world, whatever it is. And then it becomes really difficult to have like a normal conversation about a real issue.

Because if we want to have that normal conversation, the second I do, I’m giving fodder to the haters to say things that make it even worse and I don’t want to make it worse for the Jews. So it’s so darn difficult.

But what I want to ask you, Haviv, to do is I want to have like a real pedagogical conversation about the story of what people describe as settler violence. And to give language to people who are listening in good faith and not to people who are not listening in good faith.

So the different sides of the debate look like this. is a question about whether or not there has been a major uptick in settler violence and it’s showed up a lot in the news and specifically by a group called the Noar Hagevaot in Hebrew or the Hilltop Youth, and first of all, let me pause there. Who are the Hilltop Youth? Who are they?

Haviv: Yeah, that’s what they’re called everywhere. That’s how I’ve translated them at the Times of Israel for many years. It’s technically translated, the translation would be Youth of the Hills. And I mentioned that there are roughly, let’s say 140 recognized settlements recognized by Israel. There are another, let’s say again, some of these are very scattershot. Some of these come and go, but 200, what I just called wildcat outposts, I think I called them. Some of that is them. Not all of the non-recognized illegal outposts on the hills of the West Bank is them, but some number.

These are young people, some of them , some of them really coming from bad situations, bad homes. They find camaraderie, they find meaning in joining in these communities that build, you know, as they see it, that lay anchors in the ancient historic Jewish biblical heartland to ensure that the Jewish people’s home is never again lost to the Jewish people. That’s how they would characterize what it is that they’re doing. And they do it with these capturing another hill and taking another hill next to it.

Often these are tent encampments, a caravan that they drive up there with some truck. And sometimes with military protection, sometimes the local regional council, which might support it, some of these caravan kinds of outposts turned into recognized settlements over the years. And so that’s something that some of these regional councils, the Israeli local government of the different groups, of the different towns and villages of Israeli settlers, favor these things.

When we talk about the youth of the hills or the hilltop youth, we’re talking about the most distant, the most wildcat, the most independent from any kinds of institutions. And some of them, not a lot, not all certainly, but some of them, there are different estimates. Some people talk about dozens of activists. Some people talk about low hundreds of activists. But that’s the range, see their presence on those hilltops as a kind of rebellion. A rebellion against what they perceive as Israel being far too squeamish, far too unwilling to claim its birthright, far too unwilling to face down the Palestinian claim to these lands, and far too willing to exact costs for pioneering Jews like themselves as they see it, and not exact costs for Palestinians.

They have gotten into a tremendous number of altercations with Palestinians, hundreds over the last, I don’t know what, two, three years. And it causes a lot of problems. People should understand also there have been repeatedly, like clockwork, every couple of years, attacks by some members of this social group, it’s very informal, it’s very disorganized, but there’s nevertheless a distinct group of people that is recognizable when we talk about the youth of the hills. They’ve attacked IDF soldiers because crackdowns on them they perceive as the Israeli state betraying its own purpose and its own historical mission. So they’re rebels, they’re outlaws, they’re out there.

Noam: When I’ve met with hilltop youth, schmoozed with them, whatever, they come across to me as a group of people who, this is gonna maybe sound strange, but like are kind of cool. And what I mean by cool is they are, they’re rebellious, they’re mavericks. They take matters into their own hands. They’re really authentic.

They are people who don’t really care what the authority has to say about anything. They march to the beat of their own drum. And they’re basically telling the Israeli government that, listen, we don’t really care what you have to say about anything. What we care about is the Jewish heartland, listen, we’re going to go old tribal here. There’s the Palestinian tribes, there’s the Jewish tribes, and that’s like what it is to be a mountain Jew. That is what it is to be a Judea-Samaria Jew, to be a West Bank Jew. I understand that in Israeli society, I would imagine that mainstream settlers view them as dangerous and undisciplined. The Israeli security forces view them as a major threat. That left-wing Israelis view them as proof of Israel’s descent into Messianic extremism. Right-wing politicians sometimes publicly condemn the violence they privately enable or protect them. And many Israelis view them as fringe extremists, but others are either indifferent or unaware and have never met, have no idea who these people are, just like they’re a bunch of weirdos to them.

And they have the peyot, they have the long hair, they wear these t-shirts with tzitzit and religious fringes. They have the big kippah often, and they wear the sandals, the whole thing. So I just painted a picture of them. I wanted your reaction to that picture.

Haviv: They have, as you say, a very romanticized sense of themselves, of the happy good life, of they have the pioneer ideal, absolutely. They have a sense of themselves as Frederick Jackson Turner talked about the frontier as a kind of social safety valve that protected the American society because it could always export to the frontier everybody with problems, everybody who didn’t have economic opportunity, all the social classes that were struggling could go and find their way on the frontier.

And the frontier shaped not just the American imagination and sense of self, but the American society back home in profound ways. They want that. They want to be on the edge of things. They want to have a horizon. They want to think that they are carrying their society, their world, their culture forward. And that’s something that a lot of people want. It’s not off track, because I think it’s important to also understand what’s appealing in these groups.

I think Roger Ebert, the movie reviewer, he once speculated that the zombie movie genre, the post-apocalyptic wandering around in a dangerous world genre of American cinema, which at some point was literally every American movie for like 15 years. He once suggested that maybe it’s not a horror genre. It’s not about scaring us. It’s a yearning genre. It’s teasing us. It’s aspirational.

We live these very constrained lives socialized into gigantic apartment buildings surrounded by a million people. It’s very lonely to be among a million people. We want a world that is depopulated and open to us and to travel it and to face dangers and maybe to have the six people we actually need in our lives there with us totally dependent and trusting in each other. That’s the happy life that everybody who lives in a city in an apartment building yearns for. That’s what those movies are about. People want to be that survivor in the zombie apocalypse secretly out of, know, because of all the ills of modernity. That’s what they think they’re doing. And that’s what they think they get out of it.

The zombies, by the way, in this analogy, I guess would be Palestinians. It’s an analogy I’m imposing on them. Don’t blame them for it. It’s a bad analogy. My point was not to compare Palestinians and zombies. My point was they have that sense of camaraderie, of defending each other, of facing the world’s dangers, of just through sheer will and spirit standing up to all the great demands of all the assumptions of decadent civilization. It’s all there. You go there, you go to them. These are people living with very little and making a lot of it. They’re constantly getting together, finding every excuse to get together and sing songs.

Their religion is deeply authentic and very romantic. Their sense of history is very meaningful and purposeful and history arcs toward a very specific goal of redemption. All of that is there and it’s powerful and profound and very attractive. Many, many, many of them, most of them, are not violent. Not violent.

There is a problem among them, of probably hundreds of young people, who have all of that fascinating, wonderful, fun stuff that I just described, who see in the Palestinians that surround them an active and profound enemy.

Now, some of the violent encounters are tit for tats between that little Jewish outpost. Sometimes it’s really a village that’s been there 30 years already. Oftentimes it’s brand new. And a Palestinian village nearby. There’s a lot of tit for tat and it’s a response and then you ask yourself who’s at fault, you have to ask a political question. If you believe the Jews have a right to be there, maybe nobody’s at fault, or it’s a tit for tat. If you don’t believe they’re right to be there doesn’t matter, whether it’s tit for tat or if they got some attack from the Palestinians nearby. A lot of the reporting on this is also skewed by politics, a lot of the numbers are skewed by politics. You know Amit Segal, Israeli conservative journalist, wrote a great column that you and I both read that from a Hebrew University analysts who took apart a UN report on settler violence that claimed, you know, thousands of settler violence attacks.

Noam: Yeah, I actually, I want to read from that for a second. So, Amit Segal said that the inflation of settler violence from a limited phenomenon to absurd proportions is meant to soothe the world’s conscience by creating a strange kind of symmetry for the support it gives Israel in its war against the murderous Hamas. In Israel, the campaign serves the purpose of expelling settlers and establishing a Palestinian state in Judea and Samaria.

And then he cites numbers. He talks about how the UN data on settler violence from 2016 to 2022 is 5,656. He talks about 1,600 incidents in Jerusalem. Almost all our Jewish visits to the Temple Mount or police clashes with Muslim rioters. He talks about 2,500 incidents classified as property damage or physical.

Haviv: The entirety of the first part is nothing to do with settler violence. I just want to make sure people understood that.

Noam: Say more.

Haviv: Israelis visiting the Temple Mount is controversial by the way, Judaism, Orthodox Judaism is controversial. And we can debate it, we can discuss it, and police clashing with Palestinians who are responding to Israeli visitings. And you can, by the way, oppose it and you can criticize it, but it’s got nothing to do with what we would call settler violence.

Noam: That’s right. Right. Correct. Right

Haviv: And it’s lumped in because, technically the old city of Jerusalem is over the green line, but it’s just a whole different social and political phenomenon that’s not related to that other phenomenon.

Noam: Okay, so there’s been Palestinian terror attacks where the terrorist was killed, which is included. There’s clashes at Joseph’s tomb. There’s entering the tomb of Joshua. Traffic accidents are included when they involve settlers and Palestinians. And his conclusion is that about 20 violent incidents per month happen, so roughly 20, 240 per year, and most of them mutual or unverified.

There’s also IDF data on Palestinian attacks from 2019 to 2022 in which 25,257 Palestinian attacks on settlers over four years. That’s around 6,314 per year. And in 2023, there were 763 attacks on settlers.

And someone else that I saw posted the following. Said that, listen, I got to tell you something. Settler violence reports are absolutely exaggerated and fabricated. It’s an easily verifiable fact, this person writes that the overwhelming majority upwards of 90% of settlers are peaceful and oppose vigilante violence against Palestinians. So my friend, is there such a thing as settler violence as a problem or is it something that is out, totally focused on a bit too much? It’s politicized. Which one is it? Is there a problem with settler violence or is there just violence like in any community?

Haviv: Yeah. I’m really glad you had that ready because it is absolutely blown statistically, the numbers, way out of proportion. One of the examples that this Hebrew University examination deep dive into the UN numbers revealed was a Palestinian, a terrorist, who had attacked, carried out an attack in Maaleh Adumim, a very large city in the West Bank right outside Jerusalem, and his being shot while he’s carrying out an attack counts as settler violence in this report. And the next day he died of his wounds in hospital and that counted a second time as a second act of terrorist violence in this report.

In other words, it’s not real, this report. It literally just did a Google search and whatever the number at the results, line on top is what it threw in as settler violence. Yes, absolutely unquestionably it is exaggerated.

Here’s the problem. Here’s why we don’t get away from it just because it’s exaggerated numerically. It’s a kind of terrorism. It’s a kind of terrorism. Places where it’s mutual, where it’s two people bickering because they’re neighbors, I don’t know what to do with that. Yes, I imagine some of that is happening. But when the Israeli knows that they will be protected if the Palestinians come after them, and the Palestinian can’t know that, the idea of mission is to protect the Israeli. Now the idea of mission legally is also to protect the Palestinian and in general to maintain law and order in a place that doesn’t have enough. But they will more assiduously protect the Israeli by definition by nature that Israeli can activate a member of the Knesset to complain to the army if they fail to.

The Palestinians are outside the democratic feedback loop, obviously. And so it’s an imbalance and it’s a real imbalance that matters. And so when there are these attacks, they are often driven, often, not all of them, not every time. Some of them are complete fiction. Some of them are lies. The numbers are blown out of proportion in international reports that are just terrible, awful reports because they know for a fact that not a single BBC journalist or New York Times journalist is ever going to dig down and check anything.

Nevertheless, there is a number of attacks. 20 a month is a lot. 20 a month is also many attacks that are simply violence meant to abuse, push out, constantly maintain massive pressure on the civilian population of a town or village somewhere in the West Bank that this group of ideologically fervent Israelis doesn’t want to be there, doesn’t want to develop some land in between their villages that was the Palestinians but is now claimed by the Israelis. A lot of it is, we have a word for that, that’s terrorism.

Now, it’s not a massive scale to say there’s Israeli terrorism and Palestinian terrorism in a single sentence and then write them both off is ridiculous. These people represent in the Palestinian side the vast, vast majority of what Palestinians politically would vote for in the latest polls on their side to do to Israelis. The willingness to accept Hamas in the West Bank is extraordinarily popular. And Hamas is worse than these Israelis. But nevertheless, it is violence against civilians in a systematic way to create political alternative, to create a political end. It is the textbook FBI definition of terrorism.

And here’s the thing with terrorism. It doesn’t take a lot of terrorists to create a powerful effect. You don’t need 500 terror attacks in Jerusalem for the Israelis to be afraid of terrorist terror attacks. A dozen is enough. We have polls of Palestinians. When you say to them, are, do you feel vulnerable? You discover just a tremendous sense of vulnerability. One of my favorite examples is about, it must be 10 years now, where Palestinians in the West Bank were asked by a very great Palestinian pollster Khalil Shikaki, one of the more reliable ones that’s used by Gallup, were asked to, for example, explain, what they think the Jews want to do with the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Do you think the Temple Mount is going to be destroyed by them? Do they want to take it? Do they not want to take it?

80% of Palestinians in the West Bank said the Jews want to do something bad to the Temple. There were several options, build the Temple next to it, destroy it, convert it to a synagogue of some kind, different options. All the different conspiracy theories that percolate through Palestinian politics about the Israeli desires for the Temple Mount. And then Khalil Shikaki asked the most important question, the follow-up that, thank God he asked it because it framed the whole thing differently for me. These were not antisemitic conspiracy theories because they’re constantly told the Jews are coming, the Jews are coming. That, by the way, the claim that the Jews want the Temple Mount and will steal the Temple Mount is what instigated the Nebbi Musa riots in 1920 and the Hebron massacre of 1929. These are ancient, ancient Palestinian theories about us.

Noam: One more, Al-Aqsa Flood you know.

Haviv: Al-Aqsa flood. Every time Hamas has ever massacred Israelis, it claimed it was for Al-Aqsa. And the Al-Aqsa Intifada is what Hamas called the Second Intifada.

Noam: Correct. Second Intifada. Exactly.

Haviv: But then he said to them, will they succeed? And here is where Hamas and the general Palestinian public diverged radically. Hamas says, of course not. God’s on our side. We’re going to fight back. We’re going to murder them all. They’re all going to leave. The ordinary Palestinian, 50% said yes. He didn’t say should they, he didn’t say could they, he didn’t say are you afraid they might, he said will they succeed in your estimation of the future? Will they succeed? 50% said they will succeed. The discourse among Palestinians about Jewish desire to steal the Temple Mount from them, it isn’t just driven by some Jews who want to do it like Ben-Gvir, it isn’t just driven by conspiracy theories among the Palestinians that have been percolating in their politics for over a century. A great deal of it is simply a vocabulary for talking about vulnerability. It’s Palestinians saying, if they wanted to, nothing could stop them. And that is a lot of how Palestinians talk about the violence in the West Bank generally.

Most Palestinians, I saw one poll a few years back that talked about 80% and things were a lot easier then, a lot gentler then, a lot less violence then than there is today. 80% expected to meet with Israeli violence in their daily lives in the cities and towns, the Palestinian cities and towns of the West Bank. Israelis don’t think settler violence is a big deal. And they don’t think it’s a big deal because as we’ve just discussed, it is a tiny phenomenon, numerically.

But it is a tiny phenomenon the state of Israel will not crack down on. And you don’t need a whole lot of attacks, terroristic attacks, attacks meant to pressure civilians for political ends to produce a massive psychological effect, especially if they’re allowed to happen over a long period of time. And so there’s a huge discrepancy between how Israelis and Palestinians understand these attacks.

And the Palestinians aren’t stupid. The UN is lying, but that’s true of almost everything happening in the Middle East for all the history of the UN. The Palestinians aren’t stupid for feeling that these are as significant as they feel they are.

And the Israelis are looking at numbers and at their own sense of what’s happening in their society and they know these people are not representative and so they think it’s a very marginal thing, which is rational. I think it’s wrong because the effect on Palestinians is much larger than the numbers on the sheet of paper, but both of these are rational responses.

Noam: See, you made a really important point about. Yes, it is true that if there are 500,000 settlers and only 1500 of them or 1200, whatever the number is, are Hilltop youth and only, you know, X number of incidents happen a month. then if you do the numbers that it comes out to 1 % or 2%, whatever the number is, even less of settlers are engaged in violence. I find that to be a little bit of a disingenuous take because, I mean, this mirrors what you just said, but terrorism is not caused by a vast majority of the percentage of a community. It’s caused by a very small percentage of a community and it’s tolerated by and sometimes endorsed by other parts of the community. You might not be able to say it out loud because it’s impolite, but it is subtly encouraged.

And I think that that’s one of the things that people are wondering about when they see these images of settler violence is, the Israeli society around them, are they a guest or are they tolerant of this? And I think that that’s something that people here in the States and around the world are wondering.

And also I think there’s a separate problem or a second image that comes to mind, which is when you see Israeli settlers, Jewish people fighting against the IDF, you just, it’s so ugly. It’s so ugly. And you wonder, are these people part of my people? Are they not part of my people? Where do I find myself in this whole story?

And I think part of it, and tell me if I’m wrong about this point, is the first two points don’t tell me I’m wrong. But on this point, historically, did some of this angst of the Hilltop youth or the passion or the conviction, did it emerge out of the failure of Gush Katif in 05 and feeling like there was no real leadership and therefore they had to take matters into their own hands. Is that a part of it for them or is that separate?

Haviv: It existed before. What happened, disengagement from Gaza, the decision of the Sharon government, already I think it begins, he begins to plan it in 2000, in late 2003, passes relevant laws and decisions in 2004, August of 2005 pulls out. That was experienced as a profound trauma for the ideological wing of the settlement movement, the religious Zionist redemptionist wing. And it was a profound trauma because Sharon, for one thing, they felt the political system was set against them unfairly. Sharon didn’t declare in his election in 2003 that he was gonna do this very dramatic thing. He belonged to the Likud party, which is the right. Most Likud voters didn’t want this probably. And yet he went and did it.

And so they felt that he hijacked his premiership against the wishes of the very people who got him into office. And they protested and their protests were sometimes very dramatic, shutting down highways. But they’re things that since then we’ve seen from many other groups. Now they were arrested, were placed in house arrest, the full force of law enforcement came down on the protesters.

A lot of the people today who have drawn the settlement movement and the Israeli right farther to the right, cut their teeth on that movement. A lot of the people behind the judicial reform of 2023 were ex-activists of Gush Katif, or people who had family kicked out of Gush Katif, out of the Israeli settlements in Gaza, by Sharon, the disengagement. So the disengagement was a moment that for many on the Israeli right radicalized them, among other things, against the high court, which approved the disengagement, and also approved their imprisonment without trial for some period to let the disengagement happen peacefully. So absolutely that general radicalization of the right end of the right, we’ll call it, that happened at the disengagement was also experienced among the Hilltop youth. And I don’t know the data, but I’m sure their numbers swelled from that moment. But I have to tell you that the numbers really swelled after October 7.

Noam: Yes.

Haviv: After October 7, very few Israelis have patience to listen to things that are not deadly. I mean, there are occasional moments where there are these, a couple of people are killed in these attacks over the course of a year. One was just killed, I think, a couple of weeks ago down in the South Hebron Hills, a Palestinian killed by an Israeli in one of these kinds of also very tense violent encounters.

That wasn’t like me saying something significant about who’s at fault. I have no idea. But these stories do come out. They do percolate. I literally just haven’t had time to look into that particular story. That’s all. But if you do look it up, you’ll hear the latest story from that sort of frontier, from that news issue.

But it’s not really that deadly and it’s not really that bad. And it’s morally disgusting. We should say last month, not three years ago or seven years ago, some of these hilltop youth laid an ambush for IDF soldiers and threw rocks at these IDF soldiers. And these IDF soldiers were hours after an operation in Ramallah that uncovered in the Palestinian city of Ramallah in the West Bank, north of Jerusalem, that uncovered a bomb-making lab belonging to some Palestinian terror group and dismantled it. And so these soldiers, reservists, who go to serve and give to all of us and protect all of us, and are doing this difficult thing in the West Bank, and they’re driving along and they face this rock-throwing ambush by these Israeli radicals. That made the news as well. So there isn’t support from Israelis, but there’s also very little patience in all the traumas and complexities. And everybody sat in their bomb shelter, people were killed by Iranian missiles, 300,000 were displaced, and tens of thousands are either damaged to their homes, and all this stuff’s happening.

It’s been a very dramatic 22 months. Nobody has patience and time for it. And that sense that everyone’s attention was somewhere else drove a fairly significant spike in violence among that group of hilltop youth, that violent wing of that particular movement. It’s small. It’s not small enough to ignore. And it has a huge impact on the psychology of Palestinians. And they’re not wrong to have it have that huge impact. And all of that is true, even if you should never believe UN numbers on this, because they’re really lies. And yet the problem is there, and it’s real.

Noam: Here’s my last question for you and it’s metacognitive. It’s a little bit on the topic as opposed to in the topic. I want to get your take on whether or not, this is something that I hear very often, that there are two different conversations that the Jewish world or the Israeli world should be having. There’s the internal conversation where, hey listen, if there’s a problem going on in the Jewish world or in the Israeli world, there’s a problem going on inside the home, then keep it inside the home and talk about it, deal with it, think about it. And then there’s a separate external conversation that should be had where that’s not the case, where you should make sure that when outside of the house, you could get in fights with your mom, with your brother, with your sister, with your spouse. But when you’re outside the house, you act nicely with them, you defend them, you support them. And so the external conversation about Israel should always be defensive towards Israel and always should be protective towards Israel.

I have a take on this, but I want to know what you think, Haviv. Like as it relates to settler violence, do you believe that we should be having one conversation internally and one conversation externally? How do you think about it?

Haviv: I mean in the age of Google Translate and AI Translate, I mean, I don’t think it’s relevant. I do feel like my main project, most of my work, okay, the audience I imagine when I write or speak or do a podcast episode is Jews. I have great Catholic friends. I just don’t feel a deep need to tell them Jewish history, right? So unless they ask and I’m sure it’s polite and I’m not just haranguing them. But my audience is mostly Jews, the consumers of the times of Israel or different places where I work and where I speak up. The audience is not all, but mostly Jewish. And that’s how I think.

Now, half the world’s Jews speak Hebrew, and we can maybe have a conversation that’s kind of contained in Hebrew, but constantly being translated and constantly under our microscope because there’s a global campaign against Israel, but also half the world’s Jews, their native tongue, and usually the only language they know is English, which is the lingua franca of the world. And so what is it to speak in a way that I don’t have a conversation with, that I have a conversation with Jews, but don’t involve the entire world is literally linguistically impossible.

Also, I don’t know, I grew up on Herzl. I don’t give a shit what the world thinks. I don’t know if we’re allowed to curse on a history podcast. I care what people in front of me, real human beings. I love to teach. If they have thoughts about it, if they’re honest brokers, if they’re coming to learn, I’d love to explain. I don’t think we’re always okay. I don’t think we’re remotely always okay. We’re a country. We’ll make every mistake your country will make.

Noam: No, you are, you are, you’re allowed to. It’s history, it’s history.

Haviv: And we’ll invent some clever innovative ones because we’re famous for our clever innovation. But, so I, you know, I don’t, I love having that conversation beyond the boundaries of the Jewish world, but I don’t think we need to shape ourselves, limit ourselves, hide anything. We are a decent people. We are a decent people that finds ourselves in very bad places and very difficult things.

The Palestinian cause had it been less led by Islamist ideologues descended from a certain Muslim Brotherhood line that are willing to burn everything to the ground on the altar of liberating all Palestine from every last Jew, would have long ago been successful. I genuinely believe it and I don’t believe it because it’s clever talking point. I believe it because there’s a long, long history and a very detailed history of that very thing. And when I read, you know, historians of Palestine who are just profoundly and utterly ideologues, like Rashid Khalidi, who built a campaign to demolish the state of Israel and demolish Jewish self-determination there. That’s how he wrote history and what he wrote history for. And you see it in the things he ignores and leaves out. You will read endless screeds from him on Zionism without any conversation about the fact that the Jews had no choice and were refugees with no other options, which is a slightly important fact if you want to have a kind of comprehensive social history vision of what the heck actually happened between Israelis and Palestinians and the founding of Israel.

I don’t believe that we have to limit ourselves and I believe that the true depths of our story hold up and we don’t have to ever hide them and we can’t have two conversations that somehow don’t intersect. And also we shouldn’t because we shouldn’t live in their shadow and be afraid of what they think of us, and because we have to have an honest conversation amongst ourselves.

Noam: Haviv, I couldn’t agree with you more about this inside the house versus outside the house take. I want to read to you an idea, okay? An idea from Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, who is the grandfather of Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, Joseph Bear Soloveitchik. And he talks about the topic of zealotry, okay? And here’s what he says about zealotry. I love this idea.

He tells the story of a homeowner who is troubled by an infestation of mice in his home. In order to combat the mice, he purchased a cat. In short order, the cat rid the homeowner of the troublesome mice. Rabbi Soloveitchik observed that both the homeowner and the cat shared the objective of eliminating the mice. However, their underlying motives were very different.

The homeowner would have been even happier if he had never experienced the mice infestation. However, the cat’s happiness stems from his engaging hunt and conquest. The cat’s pleasure requires that there be an infestation. Rabbi Soloveitchik explained that unfortunately some individuals delight in confrontation and conflict. They masquerade as zealots for the honor of Torah, but really enjoy confrontation and strife.

And the note here is, don’t be lazy. Everyone listening, you analogize Palestinians are mice and that’s not what this is about in the slightest. So good faith. The point is, how do we Jewish people experience the difficulty of confrontation and conflict? Is it something that we search out and say, this is our raison d’etre, we’re looking for this? Or is this something that is a necessity to deal with?

And I never want the Jewish people to act and think that they’ve become the cat in this analogy, but to be that homeowner that says, I don’t want to have conflict, this sort of conflict, this sort of confrontation, this sort of strife. I want to actually do good things in the world, and I’m not searching for strife.

And sometimes the Jewish people need to remind other Jewish people that this is the case, that we are not the cat. We are the homeowner and let’s start behaving like one. So, Haviv, those are my thoughts.

Haviv: Yeah, thank you, Noam.

Noam: Thanks for joining, Haviv.

Haviv: Wonderful. So we solved that problem, right? It’s done.

Noam: Unpacking Israeli History is a production of Unpacked, an OpenDor Media brand. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts. If you enjoyed this episode, share it with a friend who you think will appreciate it and leave us a rating on Apple or Spotify. And one last thing, I love hearing from listeners, so email me at noam@unpacked.media to share your thoughts.

This episode was produced by Rivky Stern. Our team for this episode includes Hona Dodge, Adi Elbaz, and Rob Pera. I’m your host, Noam Weissman. Thanks for listening. See you next week.