Now, he’s turned his considerable brainpower to promoting cutting-edge technology to create smarter humans who will be up to the task of saving us all.

“My intuition is it’s one of our best hopes,” said Benson-Tilsen, co-founder of the Berkeley Genomics Project, a nonprofit supporting the new field.

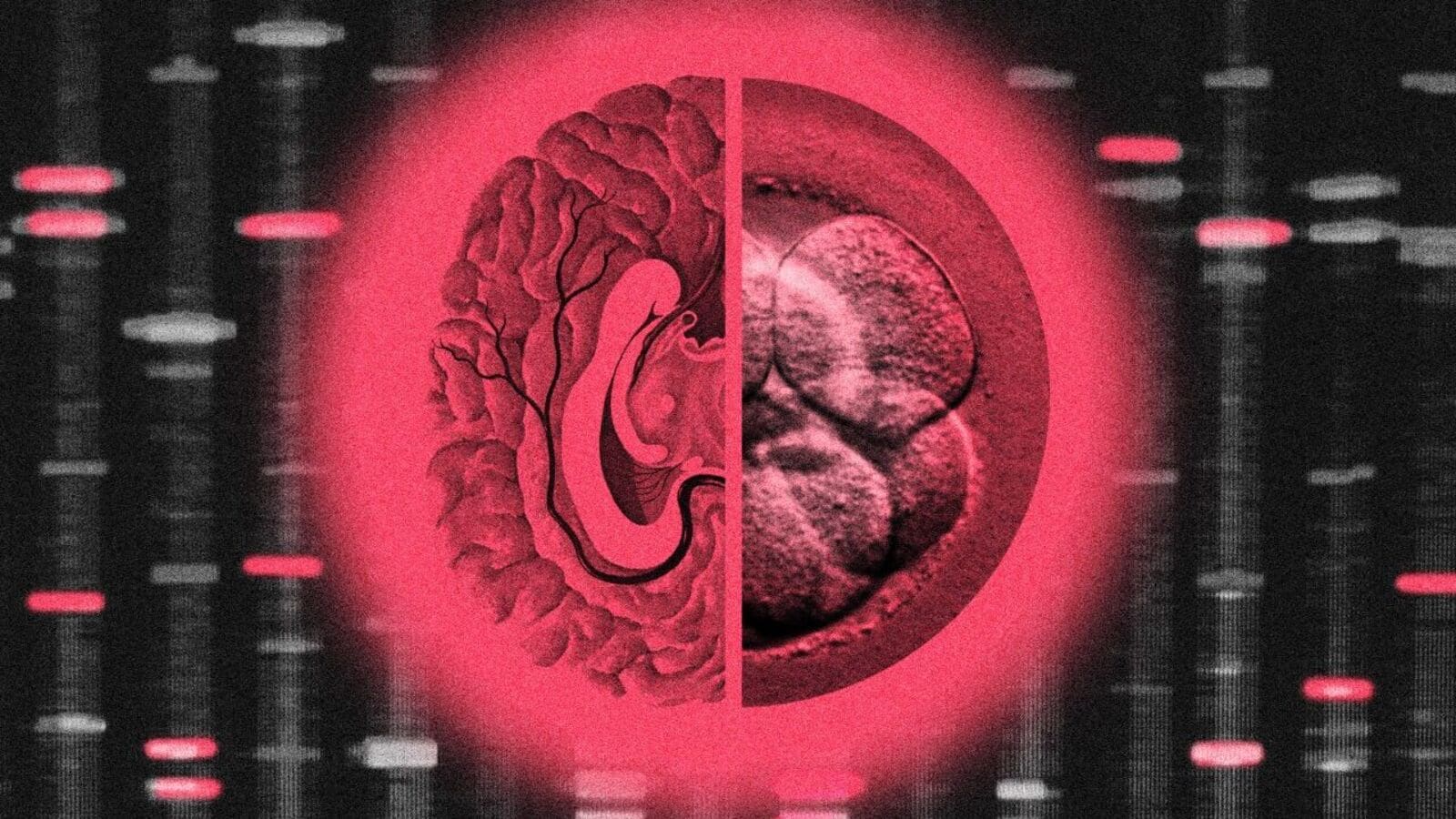

This isn’t science fiction. It is Silicon Valley, where interest in breeding smarter babies is peaking.

Parents here are paying up to $50,000 for new genetic-testing services that include promises to screen embryos for IQ. Tech futurists such as Elon Musk are urging the intellectually gifted to multiply, while professional matchmakers are setting up tech execs with brilliant partners partly to get brilliant offspring.

“Right now I have one, two, three tech CEOs and all of them prefer Ivy League,” said Jennifer Donnelly, a high-end matchmaker who charges up to $500,000.

The fascination with what some call “genetic optimization” reflects deeper Silicon Valley beliefs about merit and success. “I think they have a perception that they are smart and they are accomplished, and they deserve to be where they are because they have ‘good genes,’” said Sasha Gusev, a statistical geneticist at Harvard Medical School. “Now they have a tool where they think that they can do the same thing in their kids as well, right?”

The growing IQ fetish is sparking debate, with bioethicists raising alarms about the new genetic-screening services.

“Is it fair? This is something a lot of people worry about,” said Hank Greely, director of the Center for Law and the Biosciences at Stanford University. “It is a great science fiction plot: The rich people create a genetically super caste that takes over and the rest of us are proles.”

Yet in Silicon Valley, where top preschools require IQ tests and openness to novelty runs high, parents aren’t burdened by moral quandaries of using technology to select for their children’s intelligence before birth.

‘Silicon Valley, they love IQ’

“There is a whole ecosystem now of usually super high net-worth people, or rationalist people who are obsessed with intelligence like in Berkeley, who really want to know the IQ scores so they can use that as one of the criteria for selecting their embryo,” said Stephen Hsu, co-founder of Genomic Prediction, among the earliest companies to offer genetic testing of embryos.

Startups Nucleus Genomics and Herasight have begun publicly offering IQ predictions, based on genetic tests, to help people select which embryos to use for in vitro fertilization. Bay Area demand is high for the services, costing around $6,000 at Nucleus and up to $50,000 at Herasight.

Kian Sadeghi at the Nucleus Genomics office.

“Silicon Valley, they love IQ,” said Kian Sadeghi, founder of Nucleus Genomics. That’s not necessarily what parents elsewhere value most. “You talk to mom and pop America…not every parent is like, I want my kid to be, you know, a scholar at Harvard. Like, no, I want my kid to be like LeBron James.”

Among those who’ve turned to such testing are Simone and Malcolm Collins, leaders in the budding pronatalist movement, which encourages lots of babies. The couple, who worked in tech and venture capital, have four children through IVF, and used Herasight to analyze some of their embryos.

Simone Collins said they chose the embryo she is now pregnant with because it had a low reported risk for cancer. But they were also happy because he was in “the 99th percentile per his polygenic score in likelihood of having really exceptionally high intelligence.”

Simone and Malcolm Collins have used genetic-screening startup Herasight to analyze some of their embryos.

“We just thought that was the coolest thing,” she said.

They plan to name him Tex Demeisen. His middle name, she noted, comes from Iain M. Banks’s science-fiction novel “Surface Detail,” after the avatar of a warship known as Falling Outside the Normal Moral Constraints.

Collins said higher intelligence is associated with many good things, such as higher income, but she really wishes there were genetic tests that could screen for ambition.

“‘I will’ matters a hell of a lot more than ‘I can,’” she said. “If grit and ambition and curiosity—if we had polygenic scores for those things we’d be much more interested.”

‘Fairly typical for computer people’

Few couples would endure the difficult and expensive process of IVF unless necessary. But one Bay Area couple, both software engineers, willingly chose it.

The couple worried about diseases in their families such as Alzheimer’s and cancer. They also cared about IQ forecasts because they hoped their kids might be able to solve the world’s important problems and enjoy the life of the mind.

They described themselves as “fairly typical for computer people” who like science fiction, logic puzzles and friendly arguments.

When the results arrived from Herasight, they made a shared Google spreadsheet and both ranked the importance of each trait.

“What percent additional lifetime risk for Alzheimer’s balances a 1% decrease in lifetime risk for bipolar?” they wrote. “How much additional risk of ADHD cancels out against 10 extra IQ points?” After vigorous discussion and some complex calculations, they came up with scores for each embryo.

The embryo with the highest total score, which also had the third-highest predicted IQ, became their daughter.

‘They aren’t just thinking about love’

How good is anyone at predicting IQ with genetic tests?

The answer is “not very good,” said Shai Carmi, an associate professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem who pioneered the models used for such predictions.

Carmi said researchers have found some correlation between cognitive ability and the cumulative effect of thousands of variants in the human genome. Current models explain about 5% to 10% of the differences in cognitive ability between people, he noted.

If parents rank their embryos by the predicted IQ, they could gain between three and four points on average compared with choosing randomly, he said. “It’s not going to be something to make your child a prodigy.”

Nucleus Genomics developed software to analyze and compare embryos.

Experts also caution about unintended consequences. Traits some may not want for their children could come along with selecting for high IQ.

“If you’re selecting on what you think is the highest IQ embryo, you could also be, at the same time unwittingly selecting on an embryo with the highest Autism Spectrum Disorder risk,” said Gusev, the Harvard statistical geneticist.

Scholars note there are more traditional, millenia-old ways to aim for a brighter kid, such as education or reproducing with another smart person. “That’s probably more fun,” said Paula Amato, a fertility doctor at Oregon Health & Science University.

In Silicon Valley, even the traditional approaches can be costly, with tech execs enlisting professionals to find intelligent partners.

“Intelligence and high IQ is discussed all the time,” said Donnelly, the high-end matchmaker, based in Dallas. Though not discussed as openly, these clients are all thinking about their future offspring.

“They want to raise high-performing children, right?” Donnelly explained. “They aren’t just thinking about love, they’re thinking about genetics, the educational outcomes and the legacy.”

‘More geniuses’

The most unusual motive for making smarter babies is emerging from a brainy group of computer scientists in Berkeley. Known as the rationalists, they fear that AI poses an existential risk to humanity.

“They think one of the ways that possibly we could make safe AI is if we had smarter humans building them,” said Hsu, the Genomic Prediction co-founder. “Some of these guys are committed to a long-term eugenics program where they create smarter humans, and the smarter humans are the ones that make AI safe.”

Benson-Tilsen, the son of a rabbi and a leader in this effort, likes to phrase his aims very carefully. He said he wants to “enable parents to make genomic choices, including raising the expected IQ of their kid.”

This element of parental choice, he said, is a critical difference between the rationalist push for smarter babies and the dark history of government eugenics programs, such as Nazi Germany’s elimination of “undesirable” people.

Benson-Tilsen said he believes people with more brainpower might be able to figure out how to make AI align with human values—or convince people not to build it at all.

“I’m interested in things that will have sort of large effects,” he said, “and in particular things that will make more geniuses, as it were.”

Write to Zusha Elinson at zusha.elinson@wsj.com