Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government made its first significant regulatory decision last week, and it might have been a poor one.

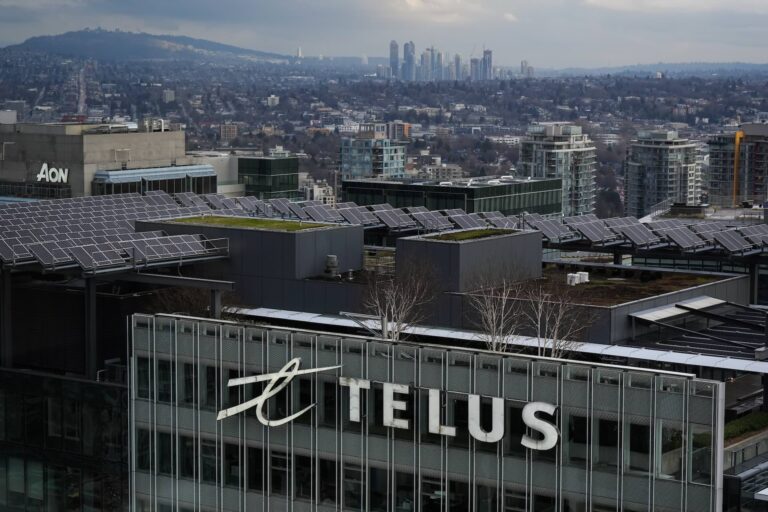

Cabinet endorsed a CRTC policy that allows Vancouver-based Telus—the country’s biggest telecommunications company by market capitalization—to present itself as a “new entrant” in Ontario and Quebec, and thus take advantage of rules designed to help upstarts stoke some competition in Canada’s notoriously uncompetitive markets for mobile and internet.

You might think that such an outcome is the result of some crass political calculation, like the one that diluted the impact of $950 million by creating a supercluster in each of Canada’s five regions, instead of seeking maximum impact by betting on one or two.

But that’s one of the things that makes this late-summer announcement by Industry Minister Mélanie Joly extraordinary. Despite heavy lobbying, politics appear to have had little to do with it. Instead, the Liberal government backed the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, no small thing at a time when the credibility of democratic institutions has been damaged by the culture wars.

Related Articles

The fallout of Carney’s decision to side with the CRTC reveals the political pressures his government was facing. The blowback is coming from Quebec, the home of seven cabinet ministers, including Joly. Montreal-based BCE, whose Bell brand sponsors the home of a certain legendary local hockey team, has said the policy will force it to slash investment in new infrastructure. Cogeco, a smaller player owned by Quebec’s Audet family, is even angrier. “I am in shock,” chief executive Frédéric Perron told the National Post this week. The Bloc Québécois called on the government to reverse its decision immediately.

You get the idea. The easy decision would have been the opposite of the one Joly announced on behalf of the government. Toronto-based Rogers, which shares a home with nine cabinet ministers, is also a critic of the CRTC’s policy. So is Nova Scotia’s Bragg Communications, the owner of Eastlink, an important internet provider in Atlantic Canada. Two cabinet ministers are fellow Bluenosers and a third is one of the prime minister’s parliamentary secretaries. “We encourage consumers to reach out to their local MP to voice concerns about this decision and the unintended consequences of losing, not gaining, sustainable competition,” Lee Bragg, executive vice chair of Eastlink, said in a statement.

It’s possible, even likely, that you are hearing about all of this for the first time. Telecommunications policy is a swamp of arcana, populated by trolls and tricksters, that repels most mortals. Here’s what you need to know.

The cost-of-living crisis compelled the previous government and the CRTC to try to manufacture competition in a notoriously concentrated industry. One of the ideas that policymakers landed on was forcing the owners of communications infrastructure to provide wholesale access to competitors at government-mandated rates.

It’s a flawed approach for the same reason rent control is flawed: All things equal, it dulls the incentive to invest. Still, you could make a decent argument for it in the case of mobile. Telus, Bell and Rogers are so entrenched that you’re never going to create competitive pressure without regulation, at least for as long as foreign ownership restrictions are in place.

Home and office internet is different. Stringing cables to buildings is expensive. Corporate boards will insist on a certain rate of return before they let management make such an investment, and that changes if you have to share those lines with companies bent on stealing your profits. This is what the outrage is about.

The addressable markets that Bell and Rogers dominate in Ontario and Quebec are much larger than those that Telus controls in the West. Bell and Rogers could theoretically piggyback on Telus’s infrastructure, but the economies of scale aren’t necessarily attractive.

For Telus, it’s the opposite. The CRTC opened a path to some of North America’s biggest urban areas, prompting chief executive Darren Entwistle to march into eastern Canada with bundles and marketing budgets that Cogeco and Eastlink can’t match, and that might force Bell and Rogers to lower prices.

Near the end of 2024, former prime minister Justin Trudeau’s government, via another Quebecois industry minister, François-Philippe Champagne, nudged the CRTC to reconsider its policy. The regulator did so, and determined in June that its approach was indeed the right one. So the bigger question facing Carney was whether an assembly of politicians should bigfoot the independent regulator. Put that way, he didn’t opt for Telus—he opted to trust Canada’s system of checks on political whim.

Carney’s decision might yet prove to have been poor because it heavily favours an incumbent at the expense of Cogeco and Eastlink, companies that created a niche by serving rural communities that the bigger mobile and internet providers tend to ignore. The objective of telecommunications policy since Stephen Harper was prime minister has been to nurture potential competitors that would end the oligopoly. Granting companies such as Cogeco and Eastlink access to legacy infrastructure makes sense. Granting Telus that privilege risks further concentration. Telus will disrupt retail prices in Toronto and Montreal in the short term, but what happens when the oligopoly resets?

Telus said on July 21 that it will invest an additional $2 billion in Ontario and Quebec over the next five years. Shareholders will want a say on that promise. TD Cowen analysts said in a note that they doubted Telus will ultimately spend “anywhere close” to that amount, because doing so could force Entwistle to exceed his capital targets, and in any case BCE likely will “step up” to protect its turf. “We doubt that Telus will end up investing much incremental capital, but we are impressed with the opportunistic PR strategy,” the analysts said.

Entwistle isn’t the villain here, nor are any of his competitors. All of them are simply seeking advantage in whatever way they can. The mistake was Trudeau’s decision to dump a political problem in the lap of the regulator. It was weak and reckless. Imagine if a big home builder had petitioned cabinet to force the Bank of Canada to cut interest rates, and the finance minister responded by asking the governor to make sure he’s looking at inflation from all angles. In retrospect, the CRTC couldn’t possibly have gone back on its original decision. Doing so would have destroyed its credibility.

The CRTC isn’t the Bank of Canada, and setting the rules of the road for internet providers isn’t as important as monetary policy. But democratic capitalism works because we trust independent agencies and regulators to provide some coherence from election to election. A political decision to undermine the CRTC would have further eroded trust in democracy at a moment when U.S. President Donald Trump is demonstrating the fragility of institutions on a weekly basis.

It might have been the wrong decision, but there are bigger questions facing policymakers than arbitrating schoolyard brouhaha in the telecommunications industry. Canada’s internet policy is a mess and it should be sorted out, but not behind closed doors at a cabinet meeting in the dead of summer. The place for that is Parliament, starting this fall.