They’ve installed new speeding cameras on Begin Road, the highway cutting through Jerusalem north to south, and I fell foul of them twice in two days.

As a result, if I didn’t want my license suspended, I was required to attend a preventive driving course — two four-hour sessions, which I chose to take on two consecutive Friday mornings.

Lesson One: Irritation to appreciation

I arrived at the designated building along with several dozen other offenders to scenes of relatively minor chaos: it wasn’t entirely clear where in the building we were supposed to go, and where or even whether we were supposed to register. An elderly gentleman, who was apparently an employee of the Transportation Ministry, collected our ID cards in seemingly haphazard fashion; there was some shouting and arguing.

But it turned out that a bespectacled woman seated at a small table in a hallway had everything pretty much under control, and we were efficiently dispatched to our respective classrooms, 35 or so in each, in good time for the scheduled 8 a.m. start. I realized I’d left my glasses in the car, so I took a seat at front right to be able to see the whiteboard clearly.

At the designated hour, a man in his 70s entered, with a kippa and a paunch, pulling a rolling suitcase. Our instructor appeared to be a jovial sort. He issued a cheery “Good morning” and began organizing his materials — pulling a screen down over the whiteboard, taking out a laptop, a pointer, and various written materials — though he seemed to be taking quite a long time doing so. He produced a thermos flask and asked me politely if it was okay for him to put it on the desk I was using; I said, Of course.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

Uri Tsihy, with his rolling suitcase, ready to teach, as seen on Kan TV in 2021. (Kan TV screenshot)

Eventually, he presented himself at front center. His name, he said, was Uri Tsihy. He apologized that his white-collar shirt was open, his tie a little low, and his belt a little loose. He had some health issues, he explained, mentioning diabetes.

He sometimes got a little dizzy, he also said, and needed to drink every 20 minutes or so from the thermos; we should remind him if he forgot, he said. He didn’t know exactly what was in the thermos, he vouchsafed, saying his wife prepared it for him, and making the first of what would prove to be a long series of asides about her, suggesting simultaneously that she was an impossible person who drove him crazy and the absolute love of his life.

Many minutes passed in his opening remarks, which included multiple quotations from holy texts, well-honed quips about his obligation to ensure that we and all we encounter on the roads get home “in the original packaging,” and numerous interruptions from our assembled ranks — a motley crew of mostly middle-aged Israelis, Haredi, Orthodox and secular, taxi drivers, office workers and academics, including a Western immigrant who spoke very little Hebrew and an immigrant from Yemen who spoke even less. “Don’t worry, I’m a Yemenite too,” Uri told this man, who did not understand him. “We Houthim, we’re such misers. We only fire one missile at a time.”

Uri Tsihy (Courtesy)

Oh, and there were five women. Five women, that is, out of 35 driving offenders — because, as we men all know, women are such lousy drivers…

“You’re here because you took your husband’s [driving infraction] points,” he asked, or rather told, one of them. “I’ll tell you later,” said she, ruefully.

After perhaps half an hour, the bespectacled woman entered to check that Uri had called our names and confirmed our presence. He had not, but promised to do so shortly; he shot a withering look at her back as she receded. Eventually, he did take the register, looking at each of us in turn, asking a kindly question or two about our heritage, saying he liked to try to remember his students’ names.

Noting that his hands shook a little as he checked off the list, he added another ailment to the list of those from which he intimated he was suffering: Parkinson’s. At the end of the class he would also tell me that he didn’t hear well when there was a hubbub of noise and was worried about this; I told him I thought it was a natural part of aging.

He then distributed small books setting out the essential road safety material we were supposed to re-master, and on which we would be tested. There would be 10 questions on the test, at the end of next week’s second session, and we could thank him for that: It used to be 20, but he’d cut it down, he said, suggesting for the first time that he was more than your average driver’s ed teacher. We’d need to get eight right, and there would be a second and even a third chance if we failed. After that, we’d have to take the course again.

He also told us, in his beautifully accented Yemenite Hebrew, that he gets paid NIS 6,000 per lecture — so the more driving laws we break, the more he earns — and that he drives a Mercedes. We didn’t know quite what to make of that.

Finally, with most of the first hour gone, he began going through the material — indulging interruptions, showing no irritation when phones rang even though he’d ask us to turn them off, and peppering his instructions about mirror settings, behavior at junctions, U-turns and braking distances with more holy quotations and further denigratingly affectionate references to his wife.

Initially, I found the class infuriating. It was my own fault that I was there, of course. But the combination of this elderly, eccentric, slightly doddery fellow, the super-slow pace of instruction, the Bible quotes, the wife “jokes,” and the endless interruptions — all this on a usually free-ish, non-work Friday morning — was hard to take.

But at some point in hour two, Uri began to win me over.

Not so young himself, his impersonations of elderly folk shuffling across pedestrian crossings were both comic and empathetic. You honk at them in frustration because they’re walking so slowly, but that’ll backfire, he warned; they’ll stop in dismay and start looking to see if they’ve dropped their phones, so you’ll be waiting even longer.

And the nuggets of philosophy he dropped into his presentation were worldly and wise, including: Don’t argue with other drivers, ever, since you don’t know how unpleasant they might prove to be: “It’s far better to be cowardly and alive than brave and dead.”

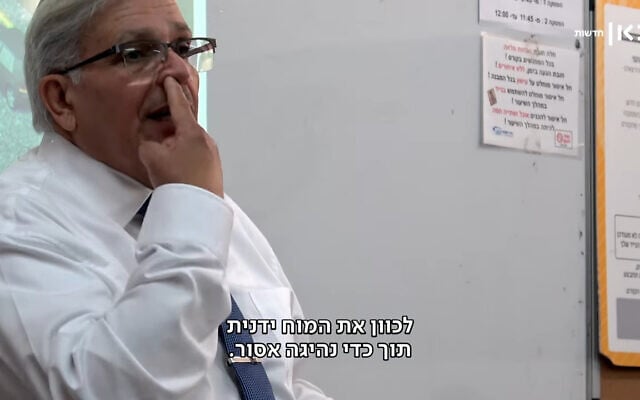

Don’t try to steer your brain from the inside: Uri Tsihy teaches driver’s ed, as seen on Kan TV in 2021. (Kan TV screenshot)

Some of Uri’s one-liners were pretty funny, albeit oft-repeated: Don’t try to steer your brain from the inside when waiting at traffic lights, he advised. (Illustrated with a finger-up-the-nostril motion). So many people waiting for the green, he mused. (Illustrated with a fingers rolling snot into a ball motion.)

(All Uri’s aphorisms, jokes and quotes work better in Hebrew; take my word for it.)

He also told us that he took school groups to the Lowenstein Rehabilitation Center, and that there’s a young man there paralyzed from neck down from a traffic accident. He once asked this young man, however undiplomatically, whether his life was worth living, Uri said. And the young man replied that if, after meeting with him, young people better internalize the need for careful, defensive driving and he thus saves a life, then of course his is worthwhile.

The class as a whole — including several gentlemen with whom you most certainly would not want to get into a road-rage argument — had also warmed to Uri, appreciating his humor and his patience. He had remarked in passing that he had been a driving instructor for many years before going into driver’s ed. He now indicated that he was one of the officials responsible for drafting and amending road safety regulations, and the punishments for offenders.

He also mentioned — when asserting that women police officers were “the worst,” in that they’ll rarely give a male traffic offender and never a female a break — that his wife was a former cop. That sounded rather improbable, I thought, and I’m sure many of my classmates wondered about it too, but he didn’t make a big deal of it, so we all let it slide.

He raised it a second time, a little later, and promised to tell us the story of their meeting before the end of the class. And that he did: One day, he said, he was at the driving center waiting for a student who was taking the test. The student passed. Uri was very pleased. And amid his delight, leaving the test center, Uri ran a stop sign. A policewoman emerged — a tall, striking figure — and waved him down. I don’t think he ever told us whether she gave him a ticket, but he did say that she was now his wife of over 50 years.

This struck me as a considerable distance beyond improbable. But we already “knew” his wife was a former cop, didn’t we? And he was an Orthodox man teaching driver’s ed. Surely, he wouldn’t have made up this story, however unlikely. At any rate, while plenty of us laughed at the tale, nobody accused him of lying. We sat there, rapt and broadly believing.

Class over, I met up with my own wife of many blissful decades and naturally told her all about Uri Tsihy — my initial despair at being stuck in a room with him and my gradual appreciation of him; his unfailing good temper and unflappability; that his wife was a police officer, and the circumstances in which they met.

She laughed and said immediately, “Well, that can’t possibly be true.”

“No, really, …” I began, before realizing that she was almost certainly right, and marveling that I and everybody else in the room had believed him, lulled by his first two casual references, and thus willing to countenance the full implausible tale. I resolved to ask him the following week.

Lesson Two: Who is this man?

Our second and final Friday session began much like the first, except that there was a plastic pipe dripping from the ceiling at the front of the room, and a plastic garbage can emplaced beneath to catch (some of) the drips. Uri arrived with rolling suitcase in tow, took a while to get organized, but then focused firmly on the material, albeit with plenty of humor.

He helped ensure a latecomer evaded the bespectacled woman; she had warned that anyone late would be barred from taking the test. He told us that, in fact, we would be allowed to get up to five of the ten questions wrong, because that was such a pleasing equation: “You get five right, you pass. You get five wrong, you pass.” (The class next door, I established later, received no such dispensation.)

Two invigilators arrived — not to check that we wouldn’t cheat on the test, it turned out, but to tell us how lucky we were to have Uri teaching us. It was Uri, one of them said, who had taught most of the driver’s ed teachers. We had no idea, this invigilator added intriguingly, quite how remarkable a man Uri is.

Soon after they left, the plastic pipe emerged from the ceiling and hung down into the room like a dribbling snake. Uri asked the bespectacled woman to get a janitor. The man arrived a short while later, stood in the doorway for a few seconds gazing at the leak, pronounced “That’s okay,” and left.

Uri Tsihy teaching driver’s ed, as seen on Kan TV in 2021. (Kan TV screenshot)

Uri plowed on through road signs, fog lights, passing on the road, et al. And then, after screening a short video on how to negotiate traffic circles and several related slides, he moved undemonstratively onto another slide. “One night I dreamed I had been accepted for an interview by God,” Uri read matter-of-factly. “I asked Him what most surprised him about His children, the humans.”

“God answered,” Uri continued, “that they get bored being children, are desperate to grow up, and then are desperate to be children again. That they sacrifice their health to accumulate money, and then spend all their money trying to regain their health. That they think fearfully of the future and forget the present, so that they don’t live the present or the future. That they live as though they will never die, and die as if they never lived.”

This reading continued for a few minutes — a complete departure from the formal syllabus, obviously, though presented as just another slide. All of us, the non-comprehending and the interrupters and the formerly irritated, sat in silence, listening to what was evidently Uri’s understanding of the purpose of life and the mistakes we make, so frustrating to the Almighty, in failing to live it wisely — notably in neglecting to treat our fellow children of God as we should.

He recounted “asking God” what lessons he would like His children to internalize. “That what matters is not what you have but who you have,” God replied, via Uri. “That the wealthy man is not the man who has the most, but the man who needs the least. That it takes just a few seconds to deeply harm someone who is greatly loved, and years after that to heal them. That there are people who love you a great deal, but don’t know how to express their emotions. That money can buy everything except happiness. That a true friend is someone who knows everything about you, and loves you nonetheless.”

And he delivered what he said were God’s parting words to him: “I’m here 24 hours a day, whenever you need me. Please, Uri, just remember: People will forget what you’ve told them, and people will forget what you’ve done for them, but people will never forget what you made them feel.”

Uri Tsihy’s ‘conversation with God’ slide. (Courtesy)

There were a few seconds of quiet in the room, as we absorbed the message, and then, applause. Uri motioned with both hands, palms down. “Don’t clap,” he said. “There are some things I need to tell you.”

And then he stood there, at the front of the classroom, the plastic pipe dripping behind him, and, having delivered what he perceives to be God’s truths, set out his very personal realities — to explain to us what had brought him here, to this place where he implores people to take care of their lives and those of others.

He said he had been diagnosed with a malignant cancer 15 years ago, and the doctors had given him two weeks to live. He said he had told God that He still needed him, and that if his life were spared, he would devote the rest of it to trying to save lives. He explained that the loose collar and tie, and the low-slung pants, hid various tubes and medical devices, and that when he sometimes raises his voice, it’s because he’s in pain.

Far from being paid NIS 6,000 per lesson, he said that he does all his teaching as a volunteer — not only in these courses, but also lecturing in schools and yeshivas most every day. “If I can save a life…,” he said at the conclusion, finally allowing us to applaud him.

It took a while for the class to settle down. When we had recomposed ourselves, he told us to take out the phones we were supposed to have turned off, and enter his phone number. We could call him later in the day, he said, before Shabbat, if we couldn’t wait until early next week to know whether we’d passed the test.

Then he handed round the questions and the answer sheet, and we tackled the 10 questions. Most of the class were done in a few minutes. He helped some of us where he could, without overdoing it. He shook hands with everybody as they left. Many of them told him what a pleasure it had been.

I took longer than most, and waited a bit more after that so I could buttonhole him. I told him what a privilege it had been to sit in his class. And I asked him: that story about his wife and how he met her, was it true?

Uri started to laugh, and I explained that I’d believed it, and I’m sure the whole class did, but that I’d told my wife, and she’d immediately said it was ridiculous.

Still laughing, he asked me my wife’s name, and told me she was right — that of course it wasn’t true. It was one of the many things he says to try to make sure that those in his classes heed the really important, life-saving, stuff he is trying to get into our thick skulls. I wanted to hug him, but sufficed with a handshake, and left.

Lesson three: What really matters

On my way back to my car, a colleague from work contacted me, frustrated that somebody had let her down, and a project she was working on was not going to get done the way she wanted, and she wouldn’t be able to fix it, or at least not until next week. I told her, with atypical calm, to please not worry, that she was doing the best she could, and that she should deal with what she could today and move on, and enjoy as much of the day as she could with her family. I explained that I’d just finished a fairly remarkable driver’s ed course, and was feeling uncharacteristically temperate.

I then met up with my wife at a nearby cafe and started trying to tell her what had unfolded in this second session. First up, I told her she was, obviously, right. Uri’s wife is not a former cop. She’s actually an educator, who stopped working to help take care of him when he got sick.

Then I tried to tell her about the slide and the details of Uri’s conversation with God, with its central focus on how we ought to treat each other; and about his cancer; and about his commitment to try to save lives if his was spared. I found myself tearing up as I recounted all this. I’m not sure how well I’ve described it above, but if you had been in that classroom, and were then explaining it to someone you love, you’d probably get emotional, too.

Soon after we got home, my wife’s phone rang. I heard her say, “Oh, Uri,” and assumed it was a young kid we know and love. But no, it was Uri Tsihy. My wife had registered me for the course, so it was her number he had on file.

When she handed me the phone, Uri told me he was just calling to tell me I had aced the test — 10 out of 10. I thanked him, and said I’d told my wife all about him — that he was crazy, brilliant and inspirational. He said he was parked by the side of a road and was now laughing at the “crazy” part of the description.

I asked him if his wife was with him, because I’d like to tell her how amazing he was. He said no, but she would be in half an hour, and I could call again.

In the interim, I looked him up on the internet, and found a 6-minute Hebrew profile that Kan TV did of him in 2021. It shows Uri telling a class just like ours, “Imagine if I’d come in today and told you” — he affects a weak, wimpy voice — ‘Hello, my name is Tsihy, Uri, and I’m here to tell you about the new traffic regulations.’” Voice now fading, eyes closing, body slumping, he continues, “I’d be falling asleep, and you all would be too.” Then we see him speaking to camera and explaining, “I wake them up! Wake up!!”

Uri Tsihy pretending to fall asleep in his own class to the amusement of his audience, as seen on Kan TV in 2021. (Kan TV screenshot)

He also remarks, with eloquent imagery, that people generally come into his courses on day one with “faces like a lemon grove.” I had certainly fit that description. He looks slimmer, healthier, in the clip, and I’d say he’s a slightly softer personality now.

Before 30 minutes had passed, Uri called again. He was home now, and I could speak to his wife if I’d like to.

Batsheva came on the phone, and I told her how remarkable her husband was. I asked if she’d sat in on his courses. She said yes, but hadn’t done so for a while.

Did she know, I asked, that he tells his classes that she’s a former police officer? There was silence, and then she called out, “Uri!” — loudly, but in a tone of long-suffering amusement.

A little later, we got a Shabbat message from Uri, who had evidently added us to his WhatsApp list, encouraging us all to spread goodwill, wishing success to Israel’s soldiers, and hoping that the hostages “return speedily to their families.”

It’s taken me a few days to write this piece, and I’m still trying to make sense of all of it. I’ve told a few people the story, and one of them ventured that perhaps Uri is a Lamed Vavnik, one of the 36 unheralded special people in each generation who, according to Jewish mystical tradition, sustain the world. I have no doubt that he would ridicule the notion.

Like I said, I’m still trying to get my head all the way round this story. I’d like to think we’ll all be more careful drivers from now on. I don’t think I’ll easily forget how Uri Tsihy made me feel. But in that Kan clip, he was driving a Mercedes.