The little-known Act MP had a rare opportunity to ask three patsy questions – and gave a performance for the ages.

Echo Chamber is The Spinoff’s dispatch from the press gallery, recapping sessions in the House. Columns are written by politics reporter Lyric Waiwiri-Smith and Wellington editor Joel MacManus.

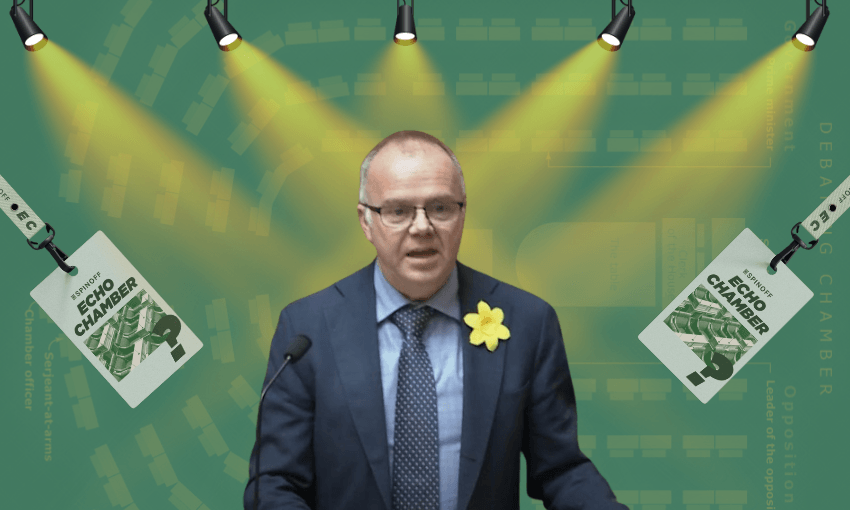

Act MP Todd Stephenson hasn’t done much to define himself in his lone term in parliament. As his party’s arts spokesperson, he’s best known for being unable to name a New Zealand book, author or play. He does, however, profess to like musicals – he saw Hamilton in New York.

As an aficionado of the performing arts, Stephenson will no doubt be deeply familiar with the methods of Konstantin Stanislavski, and specifically his famous mantra: “There are no small parts, only small actors.” And clearly, he has taken it to heart.

In parliament’s question time, there is no smaller part than the MP responsible for asking a patsy question. It’s a task foisted upon the lowliest backbench MPs, to ask a worthless question that exists only to set up a more senior minister to brag about themselves.

Most askers of patsy questions – or, at least, those with the requisite self-awareness – ask their patsies in a flat, robotic tone, simply reading out the words as blandly as possible so they can sit down again. Some do it with a wry smile, or a sarcastic tone of naivety, something that signals to the rest of the chamber (and the tragics watching at home) that they’re aware of the unimportance of their role – that they know they’re making a mockery of parliamentary process, but at least they’re in on the joke.

On Wednesday, it was Stephenson’s chance. He had a list of simple questions about the medical regulatory body, Medsafe, which would allow his leader, David Seymour, to expound on the reforms he had made to speed up approval times and how wonderful that is.

But Stephenson didn’t see this as a mere formality. Like the kid in the school production who is convinced his role as Goon #3 will launch him to Broadway fame, he knew this was his big moment – and he was not throwing away his shot. He was so eager that he initially jumped the gun and started talking before speaker Gerry Brownlee had finished calling him. Despite being asked to start again, he was undeterred. “What recent reports has he seen about Medsafe?” It was powerful. Incisive. He projected his voice, enunciating his words, demanding answers on behalf of the people.

Seymour proudly reported some “really impressive news” about Medsafe’s annual performance statistics. As he prattled on, Stephenson sat behind him, lips pursed, focused, nodding gravely. He split his gaze between his dear leader and the sheet of paper in his hand, where his next question was written. He glanced down to check the wording once, twice, thrice… 15 times. His lips started moving – he was silently rehearsing his next line.

Stephenson silently rehearsing his next line.

The split second Seymour concluded, Stephenson bounced up to ask his well-prepared supplementary: “How many working days has Medsafe reduced approval times over the last two years, and how does this compare with international benchmarks?” He was inquisitive and brave. He was Atticus Finch, Andrew Beckett, Daniel Kaffee. I want the truth. You can’t handle the truth.

Stephenson sat down again, his nerves electric. His hands fidgeted on his armrest, struggling to satisfy the adrenaline coursing through him. Seymour’s answer dragged on, boasting of reduced assessment times across various classes of drugs. The opposition grew bored and impatient. “It’s a speech,” Rachel Brooking yelled. “It’s a patsy – answer the actual question,” jeered Duncan Webb.

Taking note of the heckling, Seymour started to respond: “And for the member who had just sprung to life, though perhaps not mentally-” Speaker Gerry Brownlee was having none of that and demanded that Seymour sit down.

That brought the star of the show back again. Stephenson asked Seymour to explain the “rule of two”, a policy that would automatically allow new medicines in New Zealand if they were approved by two other similar countries. With his chest puffed and confidence at an all-time high, Stephenson sold his delivery like a young Laurence Olivier. (My only criticism being that he rushed his lines a little – but that’s an understandable mistake for any young performer on the big stage.)

Seymour recited his answer back, but the opposition was restless. Carmel Sepuloni yelled over him: “How can we take him seriously when he’s taking the piss out of someone’s mental health?” The government benches groaned with disapproval. “That was a very unnecessary interjection,” Brownlee scolded, demanding that she withdraw her comment and apologise.

Sepoluni did as she was instructed, then asked whether Seymour also needed to withdraw and apologise for attacking another member’s mental health. “He didn’t get to that. I stopped him before he did it,” Brownlee said (a fascinating interpretation of the laws of time). He gave a curt direction to Seymour: “Finish the answer, and that will be the end of the question.”

A flash of panic appeared on Stephenson’s face. He still had one more patsy to ask, and Brownlee was about to rob him of his big finale. Then, something extraordinary happened. Thinking on his feet, Seymour pivoted his answer: “I’d also like to answer what I anticipate could have been the third supplementary question by saying that in case someone was to ask for an example of a medicine that’s been assessed faster: Omjjara, a blood cancer medicine, that was approved 131 days faster than the average time last year for innovative medicine.”

The press gallery looked at each other in amazement. This was a breakthrough, a question time revolution, happening right before our eyes: parliament’s first-ever self-patsy.