Please bro, just one more house price rise will fix it. I swear.

Chris Bishop was unequivocal when asked by RNZ’s Ingrid Hipkiss last week if it’s good that house prices are falling. “I think it is,” he said. “We’ve got to decouple the idea that the New Zealand economy is driven by house prices. Actually it’s artificial wealth, and real productive wealth comes not from house prices, but from investments in manufacturing and technology and other things.” The housing minister doubled down moments later, explicitly telling Hipkiss the government was “trying” to drive down house prices, and rents, over the medium to long-term.

Bishop’s statement would have been almost unthinkable just a few years ago, when the consensus political position from left and right was that our thermonuclear housing market should continue to heat up while also becoming affordable, presumably through some as-yet undiscovered economic quantum mechanics. Hipkiss and her Morning Report co-host Corin Dann said as much following the interview. “Well that’s pretty remarkable isn’t it,” said Dann. “There was a time that a politician dared not utter that for fear of getting absolutely piled on.”

That time, as it turns out, is “right now”, if Chris Luxon’s weekly media round is anything to go by. The prime minister spent a good chunk of Monday morning softly walking back Bishop’s more bullish statements. Yes, he told Hipkiss, the government wants to see more productive investment, but don’t worry, after that things will go back to something more like normal. “What we want to see going forward is then modest, consistent house price increases,” he insisted.

Luxon’s predecessor Jacinda Ardern also championed modest, consistent house price increases, as did John Key before her. If Luxon was experiencing a nostalgic pining for the political positions of the past, he wasn’t the only one. Lately a chorus of commentators have been calling for rising house prices to jolt our deadbeat economy out of its butter coma. Over at the Herald, business editor at large Liam Dann has been arguing we need the “wealth effect” from house price inflation to get more money slushing through the country’s economic veins. He’s got backup from some heavy hitters. Key has called for a 100 basis point OCR cut to stimulate the property sector and make homeowners feel rich enough to upgrade their kitchens. Economists Jarrod Kerr and Cameron Bagrie have also touted the wealth effect from housing.

Other economists have responded, in essence, “wtf?”. The housing wealth effect is debatable on its own. Infometrics chief forecaster Gareth Kiernan sees it as a correlation causation error, pointing out high house prices have generally coincided with other factors that more meaningfully impact consumer spending, including low interest rates and low unemployment, neither of which have been present in a recession deliberately engineered by the Reserve Bank with interest rate hikes, and sharpened by cuts to government spending.

Even if rising house prices actually give a consequential number of people the confidence they need to go out and buy something big, the resulting fiscal stimulus may be a double-edged sword, worsening the shock when the economy turns and homeowners find themselves with a declining property asset and ongoing debt repayments to make on their stupid new speedboat.

Most significantly, any “wealth effect” for homeowners from high property prices tends to come with a corresponding “I’m on the bones of my arse” effect for those who don’t own homes. The economist Sam Warburton points out rising prices hurt prospective homeowners, who have to pay more to afford their first property. That ends up hurting the wider economy as those buyers cut down on spending in order to scrape together a deposit, only to be saddled with a crippling mortgage that eats up most of their disposable income. Rising prices also flow through to renters, who end up spending more of their spare cash on landlords, and less on niceties such as avocado on toast or bedrooms that aren’t riddled with black mould.

Photos of mouldy rentals submitted to The Spinoff in 2022.

Warburton draws an analogy to consumer electronics: if the government were to strictly control TV imports, resulting in the price of old TVs shooting up to $10,000, would that be an economic boon because TV owners were better off? “It’s bizarre that so many people, including economists, tout the supposed wealth effect in housing,” he says. “For no other product would we pump money into a historically supply-constrained market and say that the inflation from that is a good thing. In a recession, Reserve Banks are meant to pump money into an economy to actually produce stuff – to increase output and jobs. We should not be pumping money into an economy to do anti-social policy – transferring money from those without to those already with.”

Simplicity chief economist Shamubeel Eaqub also points to the downside risks of the so-called wealth effect on people who don’t own property, who tend to end up “despondent” even in a rising economy. “Roughly half of adults do not own. So the net effect is positive only because higher wealth people spend more, so their feeling wealthy equates to more money being spent.”

Many of these arguments are persuasive, mainly because we’ve seen them literally play out in real life for the last 30 years straight. New Zealand’s housing market lottery has always come with a side dish of despair for the people who miss out on the spoils. One prominent political thinker summed up the toxic trade-offs in a prescient 2007 speech. “Over the past few years a consensus has developed in New Zealand,” he said. “We are facing a severe home affordability and ownership crisis. The crisis has reached dangerous levels in recent years and looks set to get worse. This is an issue that should concern all New Zealanders. It threatens a fundamental part of our culture, it threatens our communities and, ultimately, it threatens our economy.”

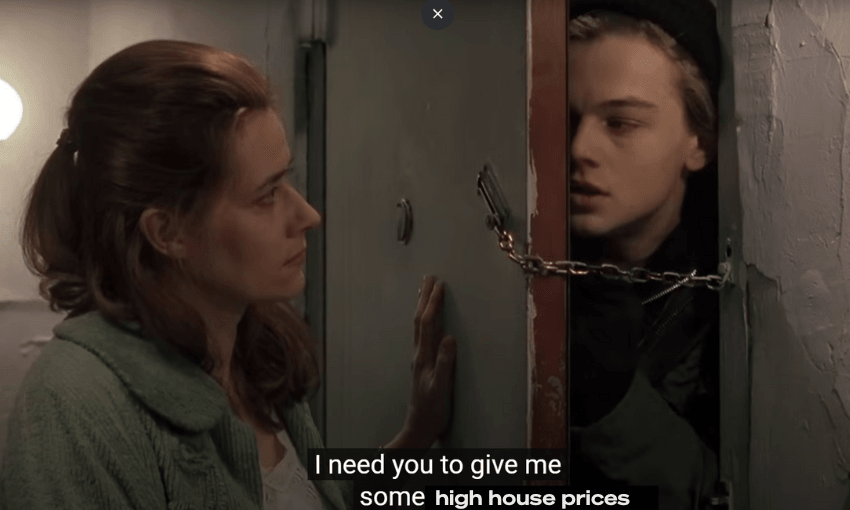

Those warnings from future prime minister John Key came to pass. New Zealand’s property market spiralled out of control under his government, and the Labour one that followed. We’ve had a homelessness crisis, an emergency housing crisis, years of stories about desperate first-home buyers, and all the while, economic commentators harping on about how we need to wean ourselves off our addiction to selling unproductive assets to each other to keep the economy running. Now there are finally some signs we’re breaking the habit, and some of those same commentators say we just need one more hit to get us through the comedown. But maybe Bishop was right. To break an unhealthy habit, sometimes you have to go cold turkey.