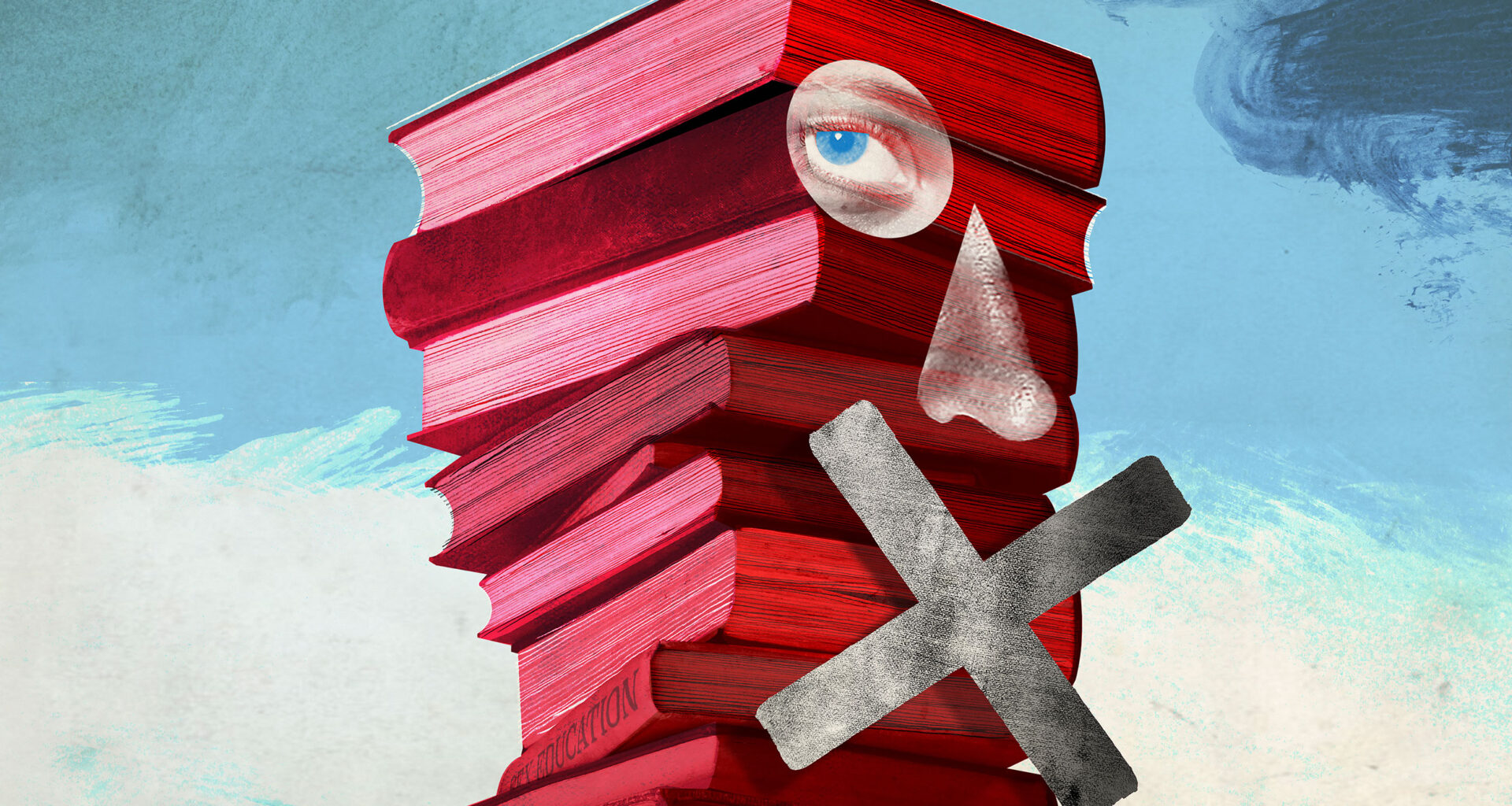

Political and social changes in the U.S. and other Western democracies in the 21st century have triggered growing concerns about possible erosion of academic freedom.

In the past, colleges and universities largely decided whom to admit and hire, what to teach, and which research to support. Increasingly, those prerogatives are being challenged.

In a new working paper, Pippa Norris, the Paul F. McGuire Lecturer in Comparative Politics at Harvard Kennedy School, looked at academic freedom and found it faces two very different but dangerous threats. In this edited conversation, Norris discusses the lasting effects these threats can have on institutions and scholars.

How is academic freedom defined here and how is it being weakened?

Traditional claims of academic freedom suggest that as a profession requiring specialist skills and training like lawyers or physicians, universities and colleges should be run collectively as self-governing bodies.

Thus, on the basis of their knowledge and expertise in their discipline and subfield, scholars should decide which colleagues to hire and promote, what should be taught in the classroom curriculum, which students should be selected and how they should be assessed, and what research should be funded and published.

Constraints on this process from outside authorities no matter how well-meaning can be regarded as problematic for the pursuit of knowledge.

Encroachments on academic freedom can arise for many different reasons. For example, the criteria used for state funding of public institutions of higher education commonly prioritize certain types of research programs over others. Personnel policies, determined by laws, set limits on hiring and firing practices in any organization. Donors also prioritize support for certain initiatives. Academic disciplines favor particular methodological techniques and analytical approaches. And so on.

Therefore, even in the most liberal societies, academic institutions and individual scholars are never totally autonomous, especially if colleges are publicly funded.

But nevertheless, the classical argument is that a large part of university and college decision-making processes, and how they work, should ideally be internally determined, by processes of scholarly peer review, not externally controlled, by educational authorities in government.

You say academic freedom faces threats on two fronts, external and internal. Can you explain?

Much of the human rights community has been concerned primarily about external threats to academic freedom. Hence, international agencies like UNESCO, Amnesty International, and Scholars at Risk, and domestic organizations like the American Association of University Professors, are always critical of government constraints on higher education like limits to free speech and the persecution of academic dissidents, particularly in the most repressive authoritarian societies.

In America, much recent concern has focused on states such as Florida and Texas, and the way in which lawmakers have intervened in appointments to the board of governors or changed the curriculum through legislation.

But, in fact, the government has always played a role, even in private universities. Think about sex discrimination, think about Title IX, think about all the ways in which we’ve legislated to try to improve, for example, diversity. That wasn’t accidental. That was a liberal attempt to try to make universities more inclusive and have a wider range of people coming in through social mobility.

So, we can’t think this all just happened because of Trump. It hasn’t. It’s a much larger process, and it’s not simply America. In all democracies, official bodies in the federal or state government, whichever party is in power, generally regulate employment conditions, university accreditation, curriculum standards, student grants and loans, and so on and so forth, and so it’s going to do that for colleges and universities in the U.S., as well.

Academic freedom is also at risk from internal processes within higher education, especially informal norms and values embedded in academic culture. Those can exist in any organization.

In academic life, surveys of academics since the 1950s have commonly documented a general liberal bias (broadly defined) amongst the majority of scholars, where the proportion of conservatives has usually been a heterodox minority.

This bias comes from a variety of different sources: It’s partly self-selection, a matter of who chooses to go into academic life versus going into the private sector careers. But is also internally reinforced — a matter of who gets selected, appointed, promoted, and who gets research grants and publications. There are lots of different ways people have to conform to the social norms of the workplace and within their discipline.

Those cultural norms are tacit. The problem is that if you don’t follow the norms, there may be a financial penalty — you don’t get promoted, or you don’t get that extra step in your grant and your award.

But they may also be just informal pressures of collegiality, friendship, and social networks. People don’t want to offend so they seek to fit in with their colleagues, department, or institution. As a result, heterodox minorities may well decide to “self-censor,” to decline from speaking up in dissent with the prevailing community.

The result is to accentuate the liberal bias, since criticisms of prevailing orthodoxies are not even expressed or heard in debate. Thus, many holding orthodox views shared by the majority in departmental meetings, appointment boards, or classroom seminars may believe that there is discussion open to all viewpoints, but silence should not be taken as tacit agreement if minority dissidents silently feel unable to speak up.

The mere perception that academic freedom is in decline increases people’s tendency to self-censor, according to the paper. Why is that?

Liberals often feel that there is no self-censorship, and there is no problem in academe, that everybody is free to speak their opinion, and that they welcome diversity in the classroom, they welcome diversity in the department, and things like that.

The problem is that if you’re in a minority and in particular right now the conservative minority, then you feel you can’t immediately speak up on a number of issues, which might offend your colleagues or might have material problems for your career.

If you’re a student and you have a heterodox view, you might feel that you won’t be popular, you won’t be invited to the parties, and you won’t have all those social networks which are a really important part of why people go to college. So, there’s this informal penalty.

Liberals don’t sense it because when they are discussing things, they think there are a variety of different views, but they may well be antithetical. They don’t even hear the criticisms of their views because those who are in the minority don’t want to speak up.

The minority can be defined in lots of different ways. It’s not simply one ideology. There are multiple viewpoints in any subject discipline. But there’s a particular way of looking at these things within a discipline, which sets the agenda, which also affects textbooks and affects the classroom, and, in fact, affects the informal culture.

You found that endorsements of strong pro-academic freedom values predict the willingness of scholars to speak out even when it differs from popular opinion. What did you mean?

Think about the people who are standing up for Harvard right now or standing up for any institution or any other unpopular view. A strong liberal is somebody who follows the John Stuart Mill argument, which is that the only way you know your argument is to know the opponent’s and to be able to act like a prosecutor in which you can put the argument on both sides. I try to use this as a pedagogy in my own classes.

People who believe in academic freedom are largely in the more liberal democracies, the Western democracies of the world. In many countries, they don’t have those luxuries.

In China, you’re not going to be speaking up against the Communist Party. It’s about what can you say and when can you say it — being sensitive to the silences and what generates the silence. And how do you ask a question, which is not going to belittle somebody and is not going to make them feel small, but you’re taking them seriously when you don’t agree with them.

The most important finding from my research evidence is that if you’re working and living in a country with more institutional constraints and less legal freedom, you’re also more likely to suppress your own views.

You can think of it as an embedded model like a Russian nesting doll. The internal group is limiting your willingness to speak up; the external is about the punishments you face if you do speak up. The two interact, obviously, but the informal norms are the subtlest things, which will keep you quiet.