A public beach in Australia’s tropical north was deemed so dangerous that authorities were forced to build a 4.5 metre-high fence to protect swimmers. Completed in December, the massive enclosure has amazed tourists from the southern states as they visit Queensland’s Whitsundays to escape what’s been a freezing winter.

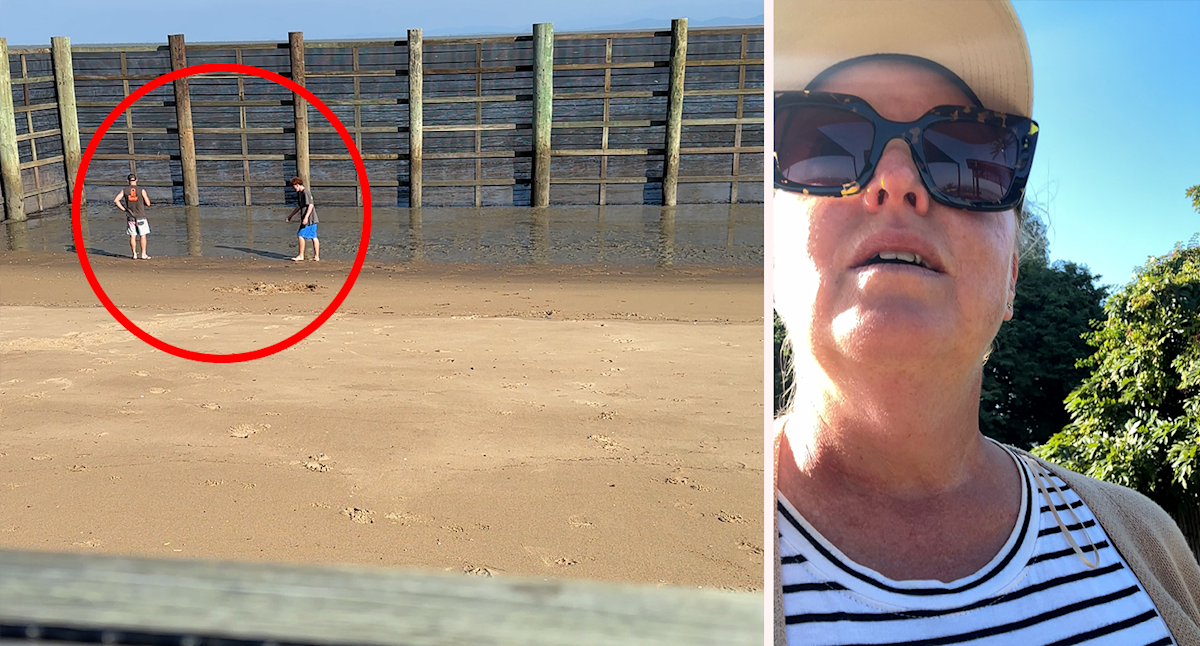

Last week, local mum Donna Buckingham shared a vision on social media showing her two sons dwarfed beneath the pen’s massive metal and wood walls. Her TikTok post is accompanied by the caption, “Have you ever seen anything like this?” and a mind-blown emoji.

Originally from Victoria, Donna is used to seeing open beaches without the need for cages or nets. Six months ago, she moved to the Airlie Beach area, and seeing the size of the enclosure left her “surprised”.

“It was like looking at a ruin that had been taken over by the water. It was so bizarre,” she said.

But as she comes to understand the dangers that surround her new hometown, she’s slowly becoming aware of why such measures are needed to keep the public safe.

Aussie mum Donna Buckingham (left) was “surprised” by the size of the large enclosure at Wilson Beach. @itsdonnabuckingam

300 crocodiles spotted close to swimming enclosure

There were two critical reasons Whitsunday Regional Council was prompted to build the 33 metre by 35 metre pen. Firstly, it’s been built at Wilson Beach at the mouth of the Proserpine River, which has the highest density of saltwater crocodiles on the east coast — a 2018 survey found just 39 during the day, but after contractors returned at night, when the reptiles like to hunt, they counted 301.

If that’s not enough to worry about, there’s also the box jellyfish, which can cause severe pain, paralysis, cardiac arrest, and even death in humans.

While swimming at a spot with so many dangers hiding under the water might seem perplexing to people who didn’t grow up in northern or central Queensland, there’s a critical community need for access to the beach, particularly when it gets hot. And perhaps no one in the world knows more about the protective enclosure than Scott Hardy, who helped manage the project during its construction and design.

He’s the manager of natural resources and climate at Whitsunday Regional Council, and while he concedes the beach can be muddy and “it’s not ideal”, it’s used by a number of locals.

“There’s no public swimming pool down at Wilson Beach. So if someone wants to go for a swim, they either need to try and find someone with a pool, or they’re going to swim in the enclosure. It’s about having accessibility to have somewhere to swim,” he said.

The new enclosure was rebuilt to help protect swimmers from crocodiles that live around the Prosepine River. Source: Whitsunday Regional Council

Events that led to construction of swimming fortress

The first swimming enclosure was built by locals in 1963, when planning laws were less restrictive, so they fashioned it out of chicken wire and wood from mangroves.

It was upgraded over the years and ultimately replaced by a more solid structure in the late 1980s. But then Cyclone Debbie damaged it in March 2017, and it was temporarily closed.

When council announced plans to restore it, there was a snag. The state government was concerned about the number of crocodiles in the Prosepine, and it asked council to demonstrate that continuing to operate an enclosure was a smart idea.

A photo from 2016 shows the older Wilson Beach structure, which was open to the beach. Source: Whitsunday Regional Council

A council-funded survey found that not only were there hundreds of crocodiles in the area, four individuals were over 5 metres long, and 12 were over 4.6 metres.

“There’s some big, big animals in there… But the community was really adamant that they wanted it rebuilt, so that’s what we had to do,” Hardy said.

Because of the abundance of saltwater crocodiles, the council was advised to reengineer the structure into the fortress it is today. There is another permanent swimming pen at Dingo Beach, along with seasonal floating marine swimming enclosures at Airlie Beach and Cannonvale, which protect swimmers from box jellyfish, but not smaller irukandji. However, the Wilsons Beach structure is by far the most secure.

To reduce the risk of crocodile attack, council had to raise the wooden structure by one metre to account for sea level rise, and also to ensure crocodiles didn’t drift over the top during king tides. It also had to enclose the landward edge and put in a gate to make it more croc-resistant.

“This is what you have to do to put in a public marine swimming enclosure in crocodile-infested waters in central Queensland,” Hardy said.

Love Australia’s weird and wonderful environment? 🐊🦘😳 Get our new newsletter showcasing the week’s best stories.