I think the new iPhones are pretty great.

The base iPhone 17 finally gets some key features from the Pro line, including the 120 MHz Promotion display (the lack of which stopped me from buying the most beautiful iPhone ever). The iPhone Air, meanwhile, is a marvel of engineering: transforming the necessary but regretful camera bump into an entire module that houses all of the phones’ compute is Apple at its best, and reminiscent of how the company elevated the necessity of a front camera assembly into the digital island, a genuinely useful user interface component.

The existence of the iPhone Air, meanwhile, seems to have given the company permission to fully lean into the “Pro” part of the iPhone Pro. I think the return to aluminum is a welcome one (and if the unibody construction is as transformative as it was for MacBooks, the feel of the phone should be a big step up), the “vapor chamber” should alleviate one of the biggest problems with previous Pro models and provide a meaningful boost in performance, and despite focusing on cameras every year for years, the latest module seems like a big step up (and the square sensor in the selfie camera is a brilliant if overdue idea). Oh, and the Air’s price point — $999, the former starting price for the Pro — finally gave Apple the opening to increase the Pro’s price by $100.

And, I must add, it’s nice to have a retort to everyone complaining about size and weight: if that is what is important to you, get an Air! I’ll take my (truly) all-day battery life and giant screen, thank you very much, and did I mention that the flagship color is Stratechery orange?

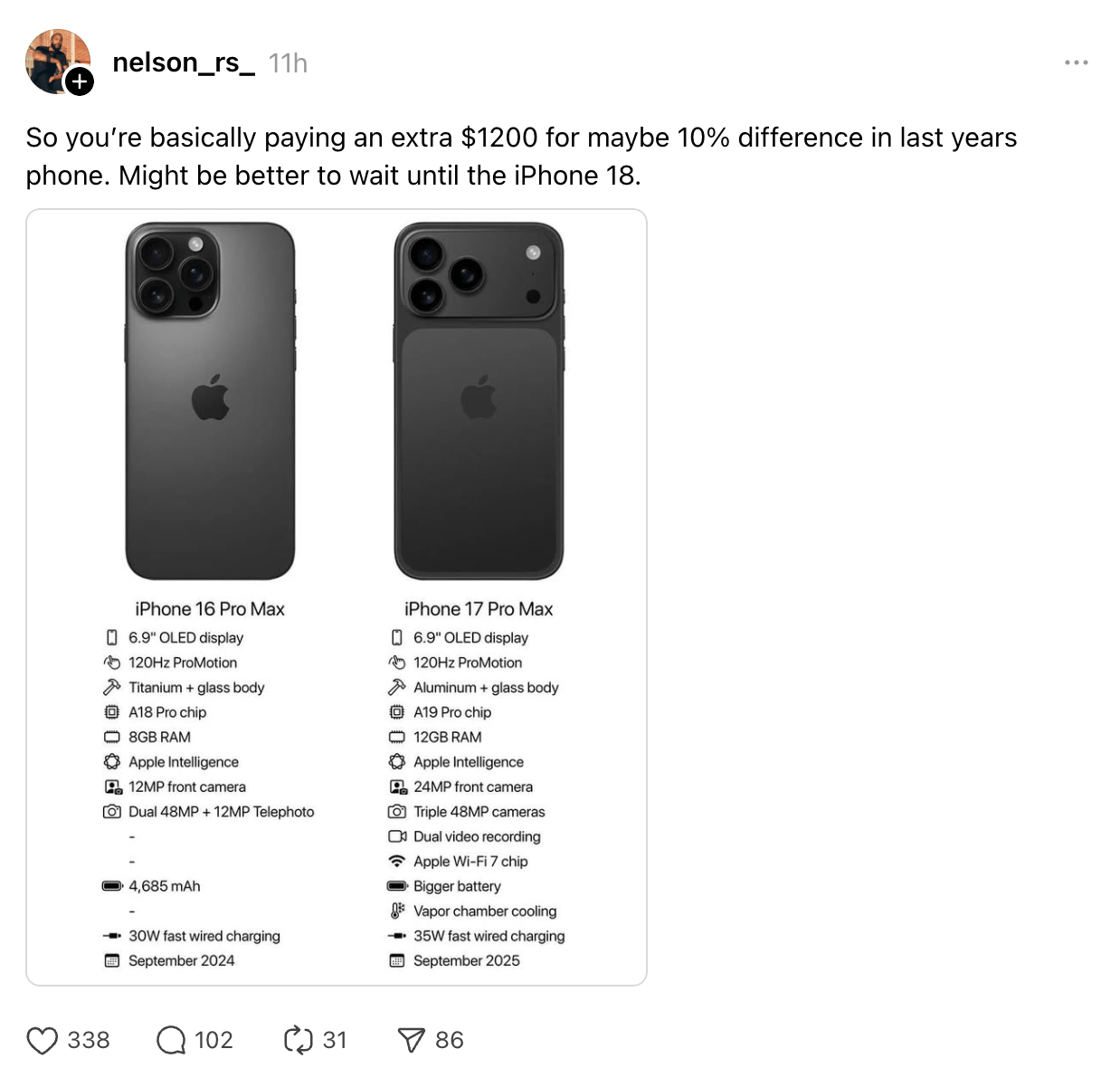

What was weird to me yesterday, however, is that my enthusiasm over Apple’s announcement didn’t seem to be broadly shared. There was lots of moaning and groaning about weight and size (get an iPhone Air!), gripes about the lack of changes year-over-year, and general boredom with the pre-recorded presentation (OK, that’s a fair one, but at least Apple ventured to some other cities instead of endlessly filming in and around San Francisco). This post on Threads captured the sentiment:

This is honestly very confusing to me: the content of the post is totally contradicted by the image! Just look at the features listed:

There is a completely new body material and design

There is a new faster chip, with GPUs actually designed for AI workloads (a reminder that Apple’s neural engine was designed for much more basic machine learning algorithms, not LLMs)

There is a 50% increase in RAM

The front camera sensor has 2x the pixels, and is square

The telephoto lense has 4x the pixels, allowing for 8x hardware zoom

There is a much larger battery, thanks to the Pro borrowing the Air’s trick of bundling all of the electronics in a larger yet more aesthetically pleasing plateau

There is much better cooling, allowing for better sustained performance

There is faster charging

This is a lot more than a 10% difference over last year’s phone! Basically every aspect of the iPhone Pro got better, and did I mention the Stratechery orange?

I could stop there, playing the part of the analytics nerd, smugly asserting my list of numbers and features to tell everyone that they’re wrong, and, when it comes to the core question of the year-over-year improvement in iPhone hardware, I would be right! I think, however, that the widespread insistence that this was a blah update — even when the reality is otherwise — exposes another kind of truth: people are calling this Update boring not because the iPhones 17 aren’t great, but because Apple no longer captures the imagination.

Apple in the Background

One of the advantages of living abroad is how you gain a new perspective on your home country; one of the surprises of moving back is running head-on into accumulated gradual changes that most people may not have noticed as they happened, but that you experience all at once.

To that end, I have, for the last several years, noted how, from a Stratechery perspective, iPhone launches just aren’t nearly as big of a deal as they were when I first started. Back then I would spend weeks before the event predicting what Apple would announce, and would spend weeks afterwards breaking down the implications; now I usually dash off an Update that, in recent years, has been dominated by discussions about price and elasticity and Apple’s transition to being a services company.

What was shocking to me, however, was actually watching the event in real time: my group chats and X feed acknowledged that the event was happening, but I had the distinct impression that almost no one was paying much attention, which was not at all the case a decade ago. And, particularly when it comes to tech discussion, you can understand why: by far the biggest thing in tech — and on Stratechery — is AI, and Apple simply isn’t a meaningful player.

Indeed, the most important news they have made has been their announcement that they were significantly delaying major features that they promised (and advertised!) as a part of Apple Intelligence, followed by a string of news and rumors about reorganizations and talent losses, and questions about whether or not they should partner with or acquire AI companies to do what Apple seems incapable of doing themselves. Until those questions are rectified, why should anyone who cares about AI — which is to say basically everyone else in the industry — care about square camera sensors or vapor chambers?

Apple’s Enviable Position

I can, if I put my business analyst hat on, make the case that Apple is doing better than ever, and not just in terms of making money. One underdiscussed takeaway from this year’s announcements is that the company, which originally had the iPhone on a two-year refresh cycle in terms of industrial design, before slipping to a three-year cycle (X/XS/11 and 12/13/14) over the last decade, is back to two years: the iPhones 15 and 16 were the same, but the iPhone 17 Pro in particular is completely new, and there is a completely new model in the Air as well. That suggests a company that is gaining vigor, not losing it.

Meanwhile, there is the aforementioned Services business, which is growing inexorably, thanks both to the continually growing installed base, and the fact that people continue to spend more time on their phones, not less. Yes, a lot of that Services growth comes from Google traffic acquisition cost payments and App Store fees, but those aren’t necessarily a bad thing: the former speaks to Apple’s dominant position in the attention value chain, and the former not only to the company’s hold on payments, but also the massive growth that has happened in new business models like subscriptions.

Moreover, you can further make the case that the fundamentals that drive those businesses mean that Apple is poised to be a winner in AI, even if Apple Intelligence is delayed: Apple is positioned to be kingmaker — or gatekeeper — to AI companies who need a massive userbase to justify their astronomical investments, and to the extent that subscriptions are a core piece of the AI monetization puzzle is the extent to which the App Store is positioned for even more recurring revenue growth.

And besides, isn’t it a good things that Apple is unique amongst its Big Tech peers in having dramatically lower capital expenditures, even as they are making just as much money as ever? Since when did it become a crime to not just maintain but actually grow profit margins, as Apple has for the last several years?

The Cost of Pure Profit

Back when I started Stratechery — and back when iPhone launches were the most important days in all of tech — Apple was locked into tooth-and-nail competition with Google for the smartphone space. And, in the midst of that battle, Google made a critical error: for several years in the early 2010s the company forgot that the point of Android was to ensure access to Google services, and started using Google services to differentiate Android in its fight with the iPhone.

The most famous example was Google Maps, a version of which launched with the iPhone. When it came time to re-up the deal Google wanted too much data and the ability to insert too many ads for Apple’s liking, so the latter launched their own product — which sucked, particularly at the beginning. Over time, however, Apple Maps has become a very competent product, and critically, it’s the default on iPhones. The implication of that is not that Apple won, but rather that Google lost: maps are a critical source of useful data for an advertising company, and Google lost a huge amount of useful signal from its most valuable users.

The most important outcome of the early smartphone wars, however, particularly the Maps fiasco, was the extent to which both companies determined to not make the same mistake again: Google would ensure that iPhones were a first-class client for its services, and would pay ever more money for the right to be the default for Search in particular. Apple, meanwhile, seemed to get the even better end of the deal: the company would simply not compete with Google, and add those payments directly to its bottom line.

This, of course, is why Judge Amit Mehta’s decision last week about remedies in the Google Search default placement antitrust case — specifically, the fact that he allowed those payments to continue — was hailed as a victory not just for Google but also Apple, which would see the $20+ billion of pure profit it got from Mountain View continue to flow.

What I think is under-appreciated, however, is that the old cliché is true: nothing is free. Apple paid a price for those payments, but it’s not one that has shown up on the bottom line, at least not yet. I wrote about Maps last year in Friendly Google and Enemy Remedies and concluded:

The lesson Google learned was that Apple’s distribution advantages mattered a lot, which by extension meant it was better to be Apple’s friend than its enemy…It has certainly been profitable for Apple, which has seen its high-margin services revenue skyrocket, thanks in part to the ~$20 billion per year of pure profit it gets from Google without needing to make any level of commensurate investment.

That right there is the cost I’m referring to: the investment Apple might have made in a Search Engine to compete with Google are not costs that, once spent, are gone forever, like jewels in an iPhone game; rather, the reason it’s called an “investment” is that it pays off in the long run.

The most immediate potential payoff would have been search ad revenues that Apple might have earned in an alternate timeline where they competed with Google instead of getting paid off by them. This, to be sure, would likely have been less on both the top and especially bottom lines, so skepticism about the attractiveness of this approach are fair.

There is, however, another sort of payoff that comes from this kind of investment, and that’s the accumulation of knowledge and capabilities inherent in building products. In this case, Apple completely forewent any sort of knowledge or capability accumulation in terms of gathering, reasoning across, and serving large amounts of data; when you put it that way, is it any surprise that the company suddenly finds itself on the back foot when it comes to AI? Apple is suddenly trying to flex muscles that were, by-and-large, unimportant for the company’s core iPhone business because Google took care of it; had the company been competing in search for the last decade — even if they weren’t as good as Google — they would likely at a minimum have a functional Siri!

This gets at the most amazing paradox of Mehta’s reasoning for not banning Google payments. Mehta wrote:

If adopted, the remedy would pose a substantial risk of harm to OEMs, carriers, and browser developers…Distributors would be put to an untenable choice: either (1) continue to place Google in default and preferred positions without receiving any revenue or (2) enter distribution agreements with lesser-quality GSEs to ensure that some payments continue. Both options entail serious risk of harm.

This is certainly true when it comes to small-scale outfits like Mozilla; Mehta, however, was worried about Apple as well. This was the second in Mehta’s list of “significant downstream effects…possibly dire” that might result from banning Google payments:

Fewer products and less product innovation from Apple. Rem. Tr. at 3831:7-10 (Cue) (stating that the loss of revenue share would “impact [Apple’s] ability at creating new products and new capabilities into the [operating system] itself”). The loss of revenue share “just lets [Apple] do less.” Id. at 3831:19 (Cue).

This is obviously not true in an absolute sense: Apple made just shy of $100 billion in profit over the last 12 months; losing ~20% of that would hurt, but the company would still have money to spend. Of course, you might make the case that it is true in practice, since investors may not tolerate the loss of margins that ending the Google deal would entail, which might compel management to decrease what it spends on innovation. I tend to think that investors would actually punish Apple more for innovating less, but that’s not the point I’m focused on.

Rather, what Judge Mehta seems oblivious to is the extent to which his downstream fears already manifested. Apple has had fewer products and less innovation precisely because they have been paid off by Google, and worse, that lack of investment is compounding with the rise of AI.

The Sugar Water Trap

Apple took the liberty of opening yesterday’s presentation with a classic Steve Jobs quote:

Setting aside the wisdom of using that quote when the company is about to launch a controversial new user interface design that critics complain sacrifices legibility for beauty (although, to be honest, I don’t think it looks great either), that wasn’t the Steve Jobs quote this presentation and Apple’s general state of affairs made me think of. What I was thinking of was the question Jobs posed to then PepsiCo President John Sculley when he was recruiting him to be the CEO of Apple in the early 1980s:

Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life or come with me and change the world?

iPhones are a great business — one of the best businesses ever, in fact — because Apple managed to marry the malleability of software with the tangibility and monetization potential of hardware. Indeed, the fact that we will always need hardware to access software — including AI — speaks to not just the profitability but also the durability of Apple’s model.

The problem, however, is that simply staying in their lane, content to be a hardware provider for the delivery of others’ innovation, feels a lot more like Sculley than Jobs. Jobs told Walter Isaacson for his biography:

My passion has been to build an enduring company where people were motivated to make great products. Everything else was secondary. Sure, it was great to make a profit, because that was what allowed you to make great products. But the products, not the profits, were the motivation. Sculley flipped these priorities to where the goal was to make money. It’s a subtle difference, but it ends up meaning everything: the people you hire, who gets promoted, what you discuss in meetings.

Apple, to be fair, isn’t selling the same sugar water year-after-year in a zero sum war with other sugar water companies. Their sugar water is getting better, and I think this year’s seasonal concoction is particularly tasty. What is inescapable, however, is that while the company does still make new products — I definitely plan on getting new AirPod Pro 3s! — the company has, in the pursuit of easy profits, constrained the space in which it innovates.

That didn’t matter for a long time: smartphones were the center of innovation, and Apple was consequently the center of the tech universe. Now, however, Apple is increasingly on the periphery, and I think that, more than anything, is what bums people out: no, Apple may not be a sugar water purveyor, but they are farther than they have been in years from changing the world.