This week is the 50th anniversary of Te Wiki o te Reo Māori. To celebrate, we’re running a three-part series looking at the past, present and future of te reo Māori in Aotearoa.

Ko tēnei wiki te huritau rima tekau tau o te wiki o te reo Māori. Kua hinga rima tekau tau mai i te timatanga o he wiki hei whakanuia tō tātou reo, te reo tuatahi o tēnei whenua. Mai 1975 ki ināianei, piki te nama o ngā tāngata ka whakamārama i tō tātou reo. He tohu pai tēnā, otirā, kia tata te reo Māori ki te pito o te pari. He aha ai? Tuatahi, iti te nama o ngā tāngata Māori me ngā tāngata katoa o Aotearoa e whakaako ana, e kōrero ana tō tātou reo. Kōira te manako nui mō tātou katoa. I tēnei wiki whakahirahira, ka pīrangi a Ātea ka ruku i te kaupapa o tō tātou reo rangatira. He aha te hītori o te reo? He aha te āhua o te reo Māori ināianei? He aha te āhua o te reo Māori ā tōna wā? Koinei te kōrero tuatahi e pā ana ki erā pātai. Ko te kaupapa tuatahi: kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua.

This week is the 50th anniversary of Māori Language Week. Fifty years have passed since the beginning of a week set aside to celebrate our language, the first language of this land. From 1975 until now, the number of people who understand and speak our language has increased. That is a good sign, yet at the same time, the Māori language is close to extinction. Why is that? Firstly, the number of Māori and of all New Zealanders who learn and speak our language is small. That is the great concern for us. In this important week, I want to dive into the subject of our treasured language. What is the history of the language? What is the state of the Māori language today? What will the Māori language look like in the future? This is the first piece that relates to those questions. The first theme? Looking backwards to move forward.

Rangatahi Māori will make up one third of the country’s population in the near future. (Image: New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu Taonga / https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/34391/kohanga-reo-1984)

On October 8, 1769, James Cook and his entourage rowed ashore at Tūranganui-a-Kiwa on the East Coast of Te Ika-a-Māui. There, they encountered a group of locals who had come to the beach to greet them. As is customary in Māori culture, a man stepped forward to perform a wero. Cook wrote in his journal that an attempt was made to persuade the man to “calm down”. Unfortunately, the man continued to “gesticulate and yell”, causing unease among the crew of the Endeavour. He was shot dead a short time later. As far as records show, this was the first instance of English being spoken in Aotearoa.

Before that fateful day, the only language spoken here by humans was te reo Māori. At that point in time, te reo Māori had been spoken exclusively by tāngata whenua for centuries. Studies show the language originates from the Austronesian family of languages and grew out of eastern Polynesian dialects, evolving uniquely in Aotearoa to reflect the land, environment and worldview of Māori. This branch also includes Hawaiian, Tahitian, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), and the languages of the Cook Islands, the Marquesas, and Rēkohu/Chatham Islands (Moriori). Māori and these languages share a large amount of vocabulary and grammar, reflecting a common ancestral language often referred to as Proto-Polynesian. Linguistically, te reo Māori is most closely related to Cook Islands Māori and Tahitian, with noticeable similarities in words and structure.

As these early Polynesian settlers spread across the islands, their language adapted to the new environment, leading to distinct vocabulary – for native plants, birds, landscapes, etc – and a unique identity as te reo Māori. Over time, te reo developed regional dialects, such as those of Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Porou, though they remained mutually intelligible. For centuries, te reo Māori remained an oral language, not written. However, there were many forms of storytelling within te ao Māori, including visual forms such as whakairo and tukutuku. Knowledge, history, whakapapa and cosmology were predominantly passed down through whakataukī, waiata and whakapapa recitations.

From dominance to decline

By the time missionaries arrived in the early 1800s, te reo Māori was not just the dominant language in Aotearoa, it was the language of the land. Traders, whalers and settlers quickly realised that to survive and thrive here, they needed to learn te reo. For several decades, Māori was the language of trade, negotiation and everyday life across large parts of the country.

But the arrival of larger waves of British settlers in the mid-19th century shifted the balance. As colonial institutions of government, law and education spread, English increasingly became the language of power. Te Tiriti o Waitangi, signed in 1840, was written in both te reo Māori and English – yet the differences between the two texts became a source of lasting grievance. The English version was prioritised in law and administration, laying an early marker for the dominance of English over Māori.

By the late 1800s, official policy was clear: te reo Māori was to be replaced by English. Schools established under the Native Schools Act of 1867 banned the use of te reo in classrooms. Children were punished – physically and psychologically – for speaking their own language. Generations grew up associating te reo with shame and inferiority.

The impacts of this policy were devastating. In 1900, te reo Māori was still the primary language in most Māori communities. But by the middle of the 20th century, English had become dominant in nearly every public and private sphere. Urbanisation accelerated the decline. Large numbers of Māori moved to towns and cities in search of work, where English was essential and Māori communities were fragmented.

By the 1970s, te reo Māori was on the brink. Census figures revealed a collapse in everyday use: from near-universal fluency among Māori in the early 1900s to fewer than 20% of Māori able to hold a conversation in the language by the mid-1970s. Linguists warned that without urgent action, te reo could disappear within a generation.

The petition and the birth of Māori Language Week

That crisis spurred action. In 1972, a group of young Māori, many of them students, presented a petition to parliament signed by more than 30,000 people. Their demand was simple but revolutionary: that te reo Māori be taught in schools.

The petition sparked a wider national conversation. Three years later, in 1975, the first Māori Language Week was established. What began as a symbolic initiative to raise awareness has endured as an annual reminder of both the fragility and the resilience of te reo.

The late 1970s and 1980s saw the birth of the Māori language revitalisation movement. One of the most powerful initiatives came from Māori communities themselves: kōhanga reo, or language nests, where preschool-aged children would be immersed in te reo, nurtured by kaumātua who still spoke the language fluently. The first kōhanga reo opened in 1982, quickly spreading across the country.

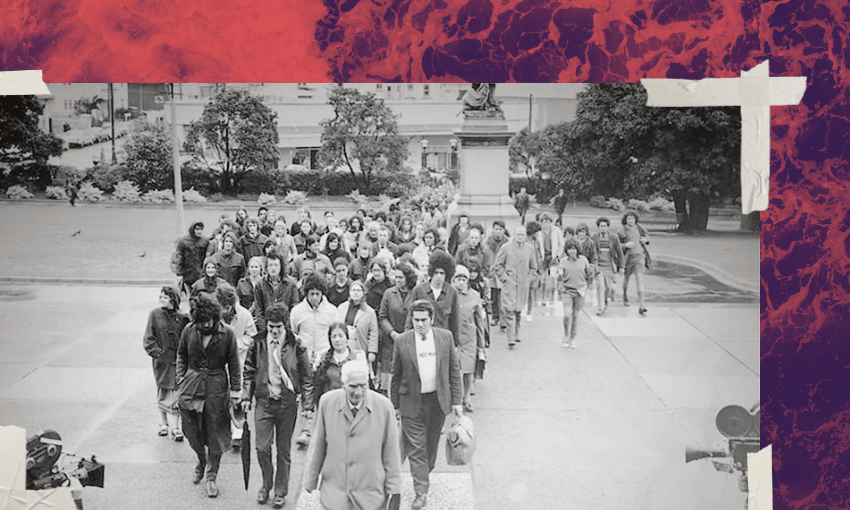

A march during Māori Language Week to demand that the Māori language have equal status with English in Wellington on August 1, 1980 (Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library)

This movement grew into kura kaupapa Māori, primary and secondary schools where te reo was the language of instruction and tikanga Māori was embedded into daily practice. By the 1990s, Māori broadcasting was also developing: iwi radio stations and Māori Television (later Whakaata Māori) all began providing spaces for te reo to be heard and normalised in homes across the motu.

Government policy began to follow. The Māori Language Act of 1987 declared te reo an official language of Aotearoa. Later, Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori – the Māori Language Commission – was established to promote and support the language.

Present day: the long road to recovery

Fifty years on from the first Māori Language Week, the reo landscape is mixed. There are genuine signs of revitalisation: tens of thousands of children enrolled in kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa Māori, an explosion of Māori media, and growing use of te reo in workplaces, politics and popular culture. Non-Māori are increasingly learning te reo, with demand for night classes, apps and online courses often outstripping supply.

But the challenges remain stark. Only around one in five Māori can hold a conversation in te reo, and among the wider population the figure is less than 5%. Many native speakers are elderly, meaning intergenerational transmission remains fragile. Experts warn that revitalisation requires not just symbolic gestures, but deep systemic support: more teachers, better resources and greater recognition of Māori knowledge systems across education, health, law and media.

The story of te reo Māori is one of survival. From being the only language of Aotearoa, to near-extinction under colonial suppression, to the grassroots fight for its return – the reo has endured. Its journey is a reminder of the deep scars of colonisation, but also of the resilience of Māori communities who refused to let it die.