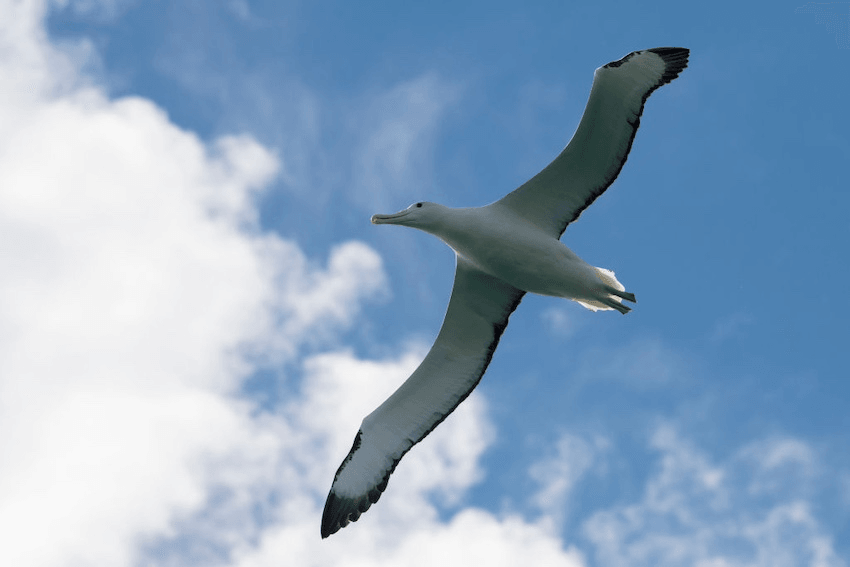

Tara Ward discovers why the annual return of the toroa means so much to Ōtepoti Dunedin.

The Rev Dr Andrea McDougall puts on a pair of black, heavy duty gloves, and grabs onto a long rope hanging from the belfry outside St Paul’s Cathedral in Ōtepoti Dunedin. At precisely 12.30pm, McDougall heaves on the rope several times until a loud “dong” booms out from the large bell above her, and once she finds her rhythm, a steady, sombre ringing echoes down through the Octagon below. Office workers on their lunch break look up and seagulls swoop down Stuart Street, while a small group of locals gather beside the belfry to ring their own handheld bells. It’s a cold, grey September day in Dunedin, but in churches, businesses and homes around the city, people have come together to celebrate a unique southern tradition.

The albatrosses are back, and Dunedin is welcoming them home.

Rev. Dr Andrea McDougall prepares to ring the bell at St Paul’s Cathedral (Photo: Tara Ward)

Every spring, the northern royal albatross (toroa) return to Taiaroa Head Pukekura at the head of the Otago Peninsula, having spent the past 12 months circumnavigating the southern hemisphere. Pukekura is the world’s only mainland albatross colony, and this year, the first toroa to glide back onto the headland was KM, a 30-year-old male described by staff at the Royal Albatross Centre as “a successful breeder” who raised 12 chicks in the last two decades. Toroa spend 85% of their lives at sea, and big daddy KM is the first of several birds who will return to Pukekura this spring, one by one, ready for the breeding season.

They’re welcoming KM back at the Royal Albatross Centre too, where around 30 people have gathered to ring one of the centre’s collection of antique handheld bells. It’s an exciting moment every year, says Hoani Langsbury, the centre’s ecotourism manager. While the toroa are expected back each spring, their actual day of arrival is unknown until the first bird is seen and identified by staff. Then, the centre sends out a thrilling email announcing the news, declaring the day and time when the welcome bells will ring out across Dunedin.

Bell-ringing has long been used to bring communities together, and while Dunedin has clanged its bells to herald the albatrosses return for many years, no one seems to know exactly when the tradition began (the earliest online media report hails from 2003). Langsbury has been asked many times, but is no closer to finding the answer. “Somewhere back in the mists of time, this tradition was created, and it carries on today,” he says.

One of 33 albatross chicks at Taiaroa Head in June 2024 (Photo: Michael Hayward/DOC)

Traditionally, the first bell rung every spring is in the whare karakia at Ōtakou Marae in Portobello, a few kilometres along the peninsula from Pukekura. Being so close to the centre means the marae bell can ring as soon as the centre learns of the toroa’s return (the region’s historic churches and schools are given a day or two notice to prepare), but Langsbury says the bell in the whare karakia is significant for another reason. The bell originally came from a schooner called Perserverance, which was one of the first vessels that traded between Dunedin and Australia before European settlement. “There was probably albatross following that ship back in the early 1800s,” he explains. “It’s just a little extra thing for that bell to be rung first.”

Pukekura is the only albatross colony in New Zealand that hasn’t seen a decline in numbers, mostly thanks to the dedication of local Department of Conservation staff. “When I started in 2013, a good season was fledging eight to 13 chicks. This season fledged 38 chicks, up from 33 the previous year,” says Langsbury. It’s a reassuring increase, but existential threats like climate change and predation mean that nearly all of last season’s chicks required some form of intervention from DOC. For Langsbury, welcoming the toroa home is a reminder of how important these creatures – and other local wildlife like kororā little blue penguin and the red-billed gull – are to the Otago community.

It’s a sentiment echoed by McDougall, who back at St Paul’s in Dunedin, has been ringing the cathedral bell for several minutes. “One of the aims of the Anglican church is to care for God’s creation, so it’s a measure of our respect and our love for the albatrosses that we take part in the city-wide welcome of them,” she says. McDougall’s colleague, the Very Rev. Tony Curtis – who was officially on leave for the week, but didn’t want to miss the bell-ringing tradition – agrees. “We really feel that we should do everything we can to support and encourage the people who are protecting our wonderful native species.”

In an ideal world, McDougall jokes, the albatross would give the people of Dunedin more notice of their arrival, so they could prepare a big celebration. “They’re very cheeky, they don’t give us any notice at all,” laughs Curtis. But in the words of Leonard Cohen, we ring the bells that still can ring, forget your perfect offering. As the final sounds of the church bell echo through the Octagon, the grey clouds above part for a brief moment, and the sun beams through. After a long, dark southern winter, spring has returned, and with it, a rare and resilient creature that offers a city connection, belonging and hope.