TORONTO — They are fraternal twins separated at birth, sharing a league but not a country, a starting line but not a pace. The Seattle Mariners and Toronto Blue Jays joined the American League as expansion teams in 1977, but for years they were opposites: Seattle the problem child, Toronto the model citizen.

It has taken nearly half a century for the Mariners and Blue Jays to play each other for the pennant. They will open the 2025 AL Championship Series on Sunday at Rogers Centre for the rare opportunity of a World Series berth.

The Mariners are the only MLB franchise to never get there. The Blue Jays haven’t been in 32 years, but they gave themselves a head start. In 1993, when the Blue Jays claimed their second World Series in a row under Cito Gaston, Lou Piniella’s Mariners scratched out their second winning season … ever.

“When Lou got here in ’93,” said Rick Rizzs, who has called Mariners games since the early 1980s, “he looked around the clubhouse and said, ‘Why aren’t you guys winning? This team is good enough to win. If you don’t want to win, I’ll get you out of here.’ And sure enough, we finally made it to the postseason for the first time in 1995.”

The Mariners lost the ALCS that year, and again in 2000 and 2001. The Blue Jays have returned twice since their World Series titles, falling in 2015 and 2016. One is about to end decades of futility.

The franchises haven’t made news together much since their inception. There was a panicked trade in 1997, when Seattle sent future 30-30 man Jose Cruz Jr. to Toronto for two relievers. The Mariners’ James Paxton tossed a no-hitter in his native Canada in 2018.

And there was an uncanny prediction in Toronto in 2009, when Mariners broadcaster Mike Blowers forecast Matt Tuiasosopo’s first career homer in eerily prescient detail:

But at the very start, the teams were simply trying to survive. The expansion Blue Jays (largely overseen by future Hall of Fame GM Pat Gillick) went 54-107. The expansion Mariners were better, at 64-98, but stayed buried in the standings for much longer.

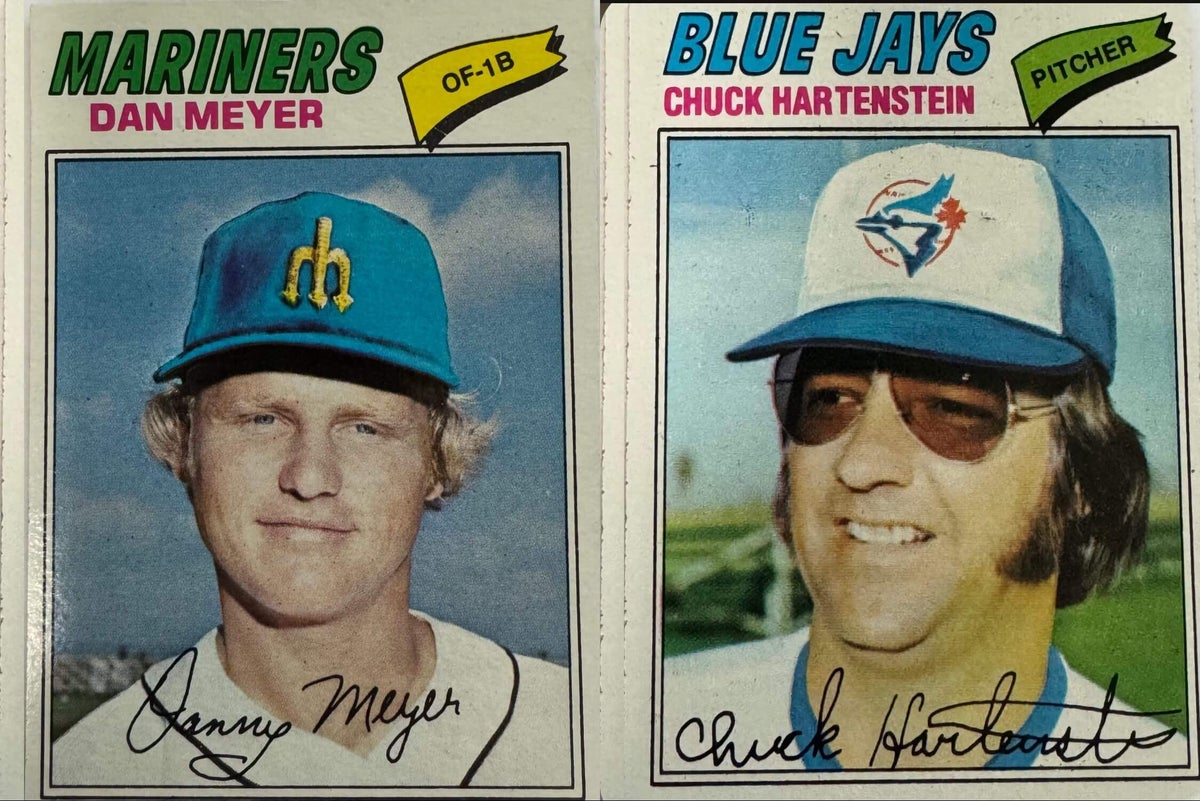

As those seasons played out, Topps introduced the new teams to collectors by including them in the 1977 set. Of course, because the cards were issued before the teams had actually played, every card is airbrushed, with hilariously haphazard results.

You won’t see any of these card numbers ending in -0, or even -5, the digits Topps awarded to the more accomplished players. These are common cards, more suitable for laughs than investments.

But every team has to start somewhere, and in 1977, this is where the M’s and Jays began. In that spirit, here’s a look at our 10 favorite cards of the folks who started it all, all photographed from my personal collection:

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

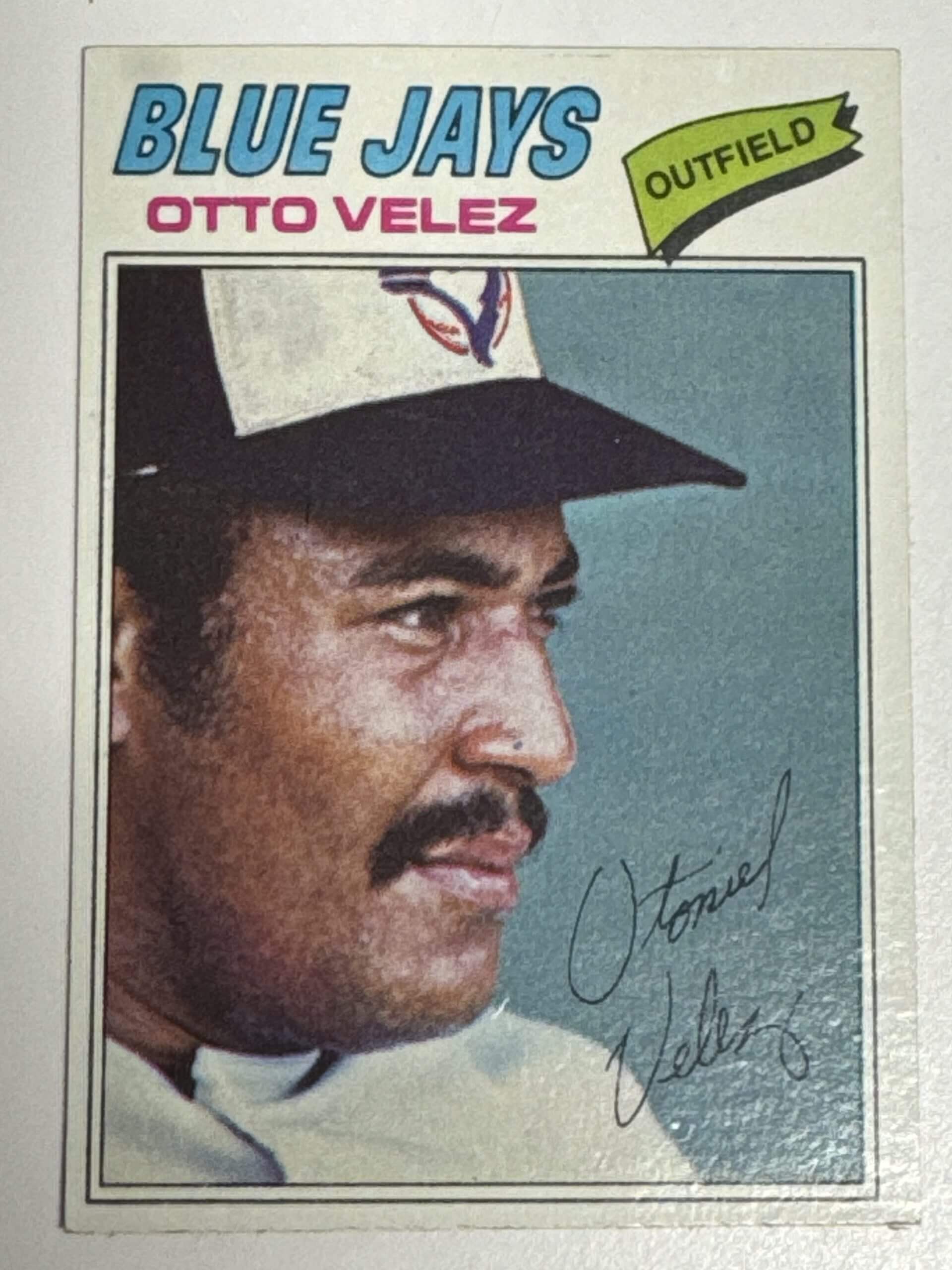

10. Otto Velez, Blue Jays, #2991977: .256, 16 homers, 62 RBI

Nothing especially goofy about the card, but expansion is made for guys like this. Velez, who had the fabulous nickname “Otto The Swatto,” had been ready for years — in 1973, at age 22, he slammed 29 homers in Triple A while drawing 130 walks.

Unfortunately for Velez, he was employed by the New York Yankees, who had a new owner eager to win right away. He stayed buried for three more seasons with George Steinbrenner’s team, but hit 16 homers for the expansion Blue Jays and posted an .834 OPS in six years with Toronto.

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

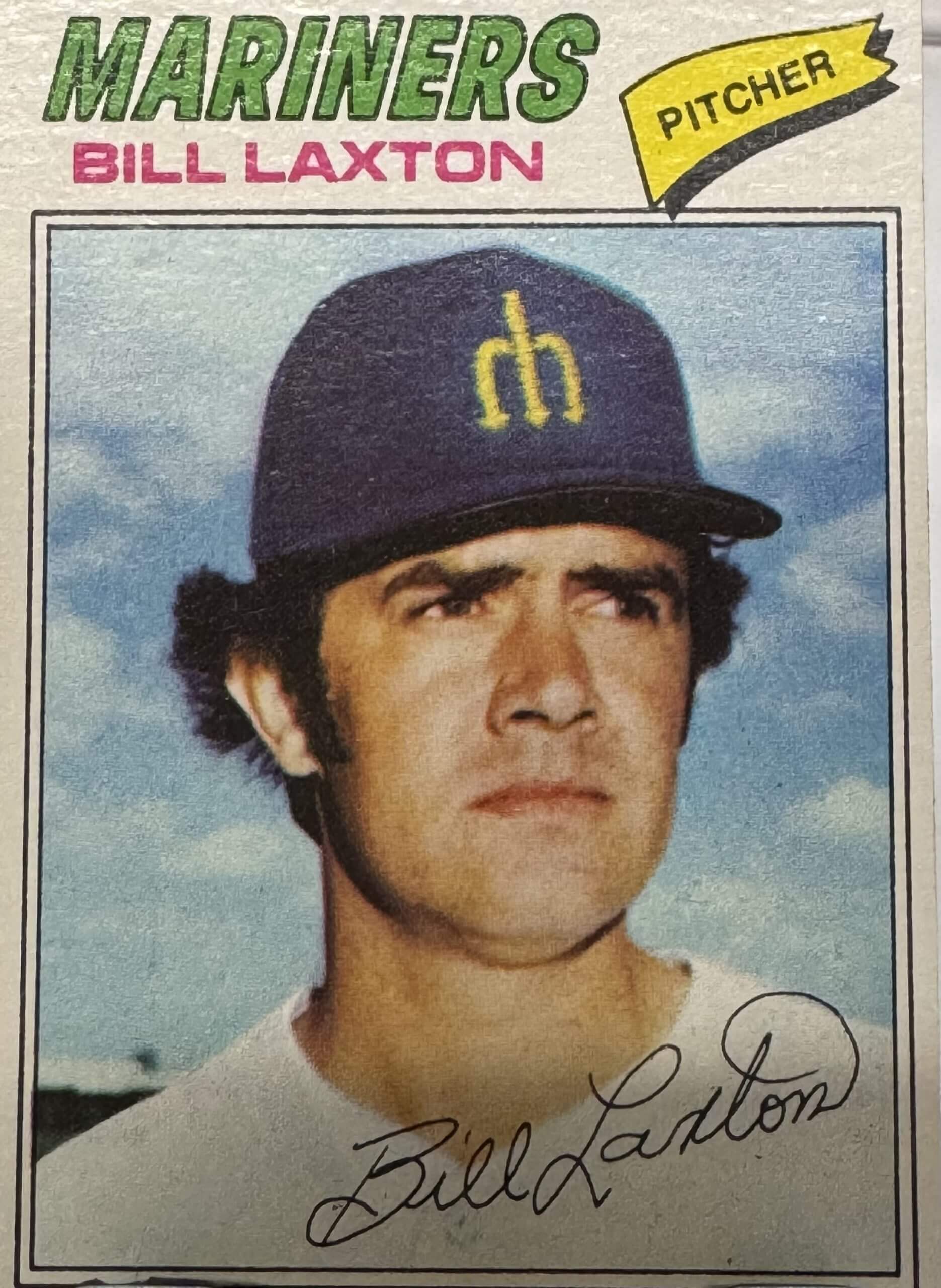

9. Bill Laxton, Mariners, #3941977: 3-2, 4.95, 43 games

Late in the 1999 season, Mariners broadcaster Dave Niehaus, who was there from the very start, pulled me aside. I was a beat writer covering the team, and Niehaus was eager to share something cool. The father of the opposing starter that day, Brett Laxton, was the first winning pitcher in Mariners history.

Brett lost that afternoon in Oakland, but Bill Laxton indeed earned the Mariners’ first victory on April 8, 1977, against the California Angels. After two shutout losses, the Mariners rallied for two runs in the bottom of the ninth, winning on a Larry Milbourne double.

That made a winner of Laxton, who had walked in the go-ahead run in the top of the ninth and had never won before himself, either. Funny to see a button on his jersey, because the Mariners wore strictly pullovers for a decade.

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

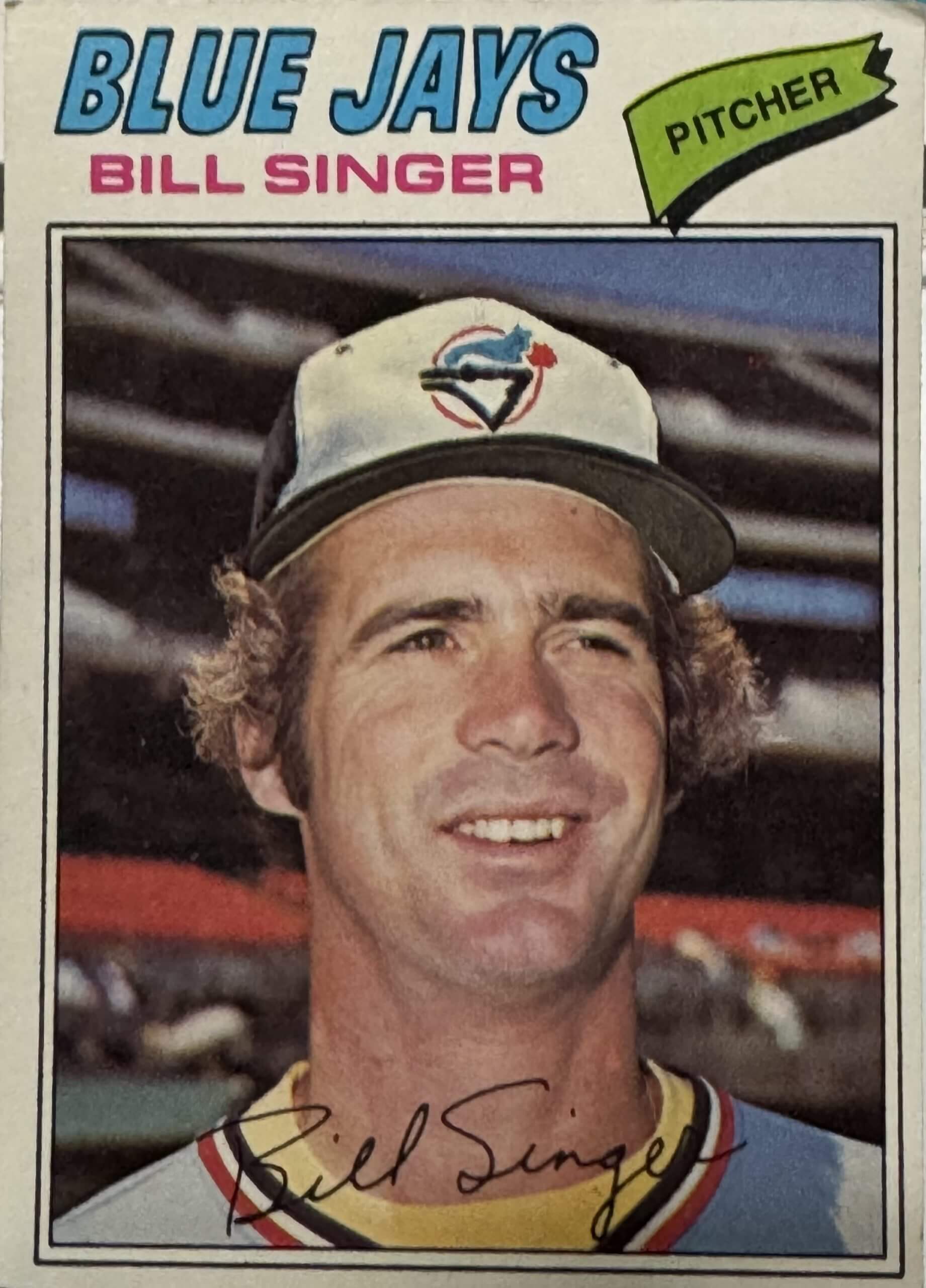

8. Bill Singer, Blue Jays, #3461977: 2-8, 6.79, 13 games (12 starts)

Topps didn’t bother to hide the red on Singer’s V-neck jersey from 1976, when he pitched for the Texas Rangers and Minnesota Twins. He had a solid season for them (13-10, 3.69) and had twice won 20 games. At 32 years old, “The Singer Throwing Machine” was a good get for the Blue Jays, and he started in the snow on Opening Day.

The first inning was a bad omen: Singer walked the leadoff man and gave up two runs, one on a homer by Richie Zisk. The Jays won anyway, 9-5, behind two Doug Ault home runs. But shoulder trouble ended Singer’s career by the All-Star break.

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

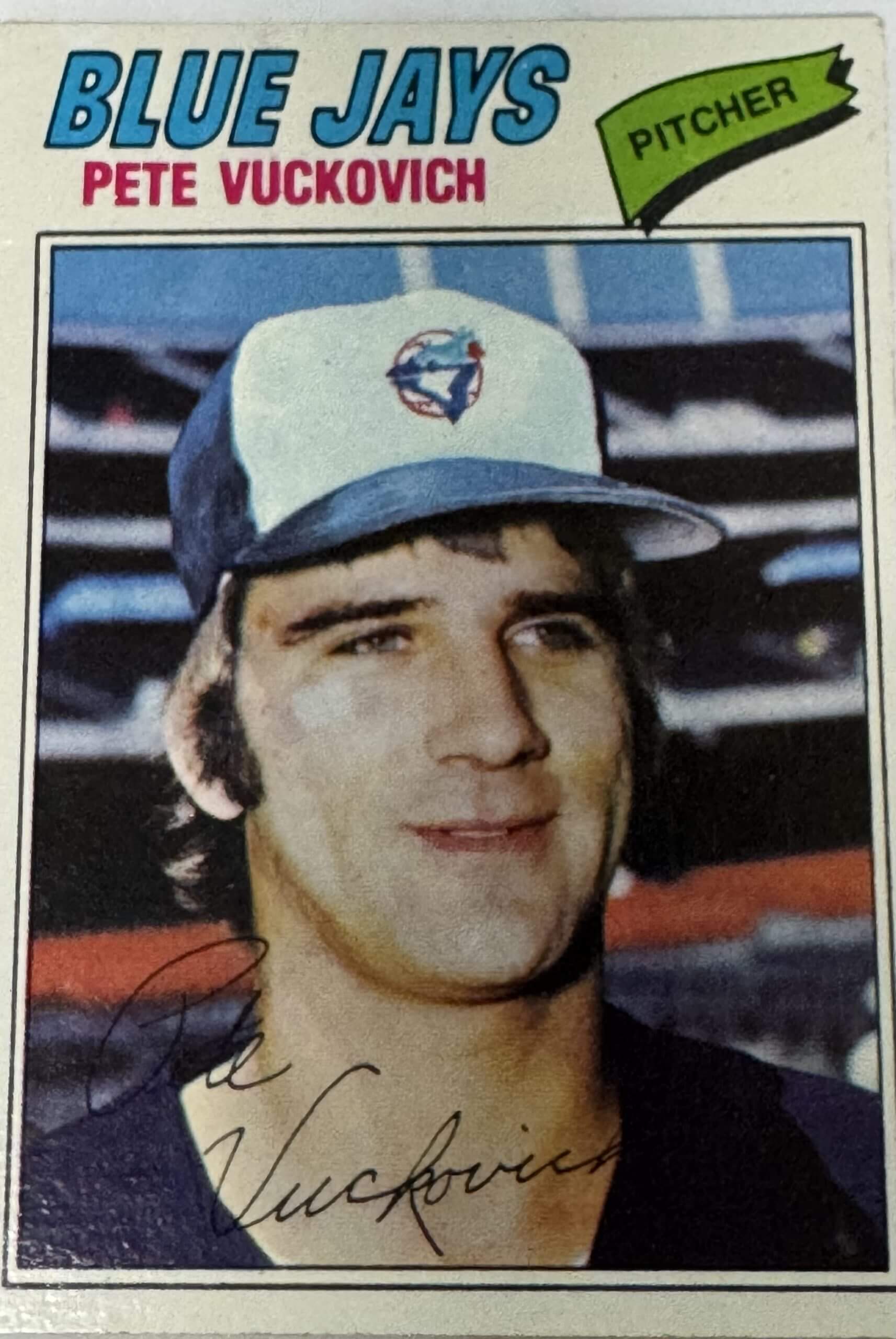

7. Pete Vuckovich, Blue Jays, #5171977: 7-7, 3.47 ERA, 53 games (8 starts)

Nobody rocked a Fu Manchu in the ’80s like Vuckovich, while winning a Cy Young Award for Milwaukee in 1982 or starring as Clu Haywood in “Major League” seven years later.

Here, though, he’s oddly clean-shaven. Vuckovich, wearing the navy jersey of the Chicago White Sox, was no older than 23 at the time of the photo. After a credible first season with Toronto, the Jays traded him to the St. Louis Cardinals for Tom Underwood.

Underwood had a much longer career than his younger brother, Pat, a Detroit pitcher who made his MLB debut against Tom in 1979. The two dueled into the ninth inning at Exhibition Stadium as the kid brother beat the big brother, 1-0.

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

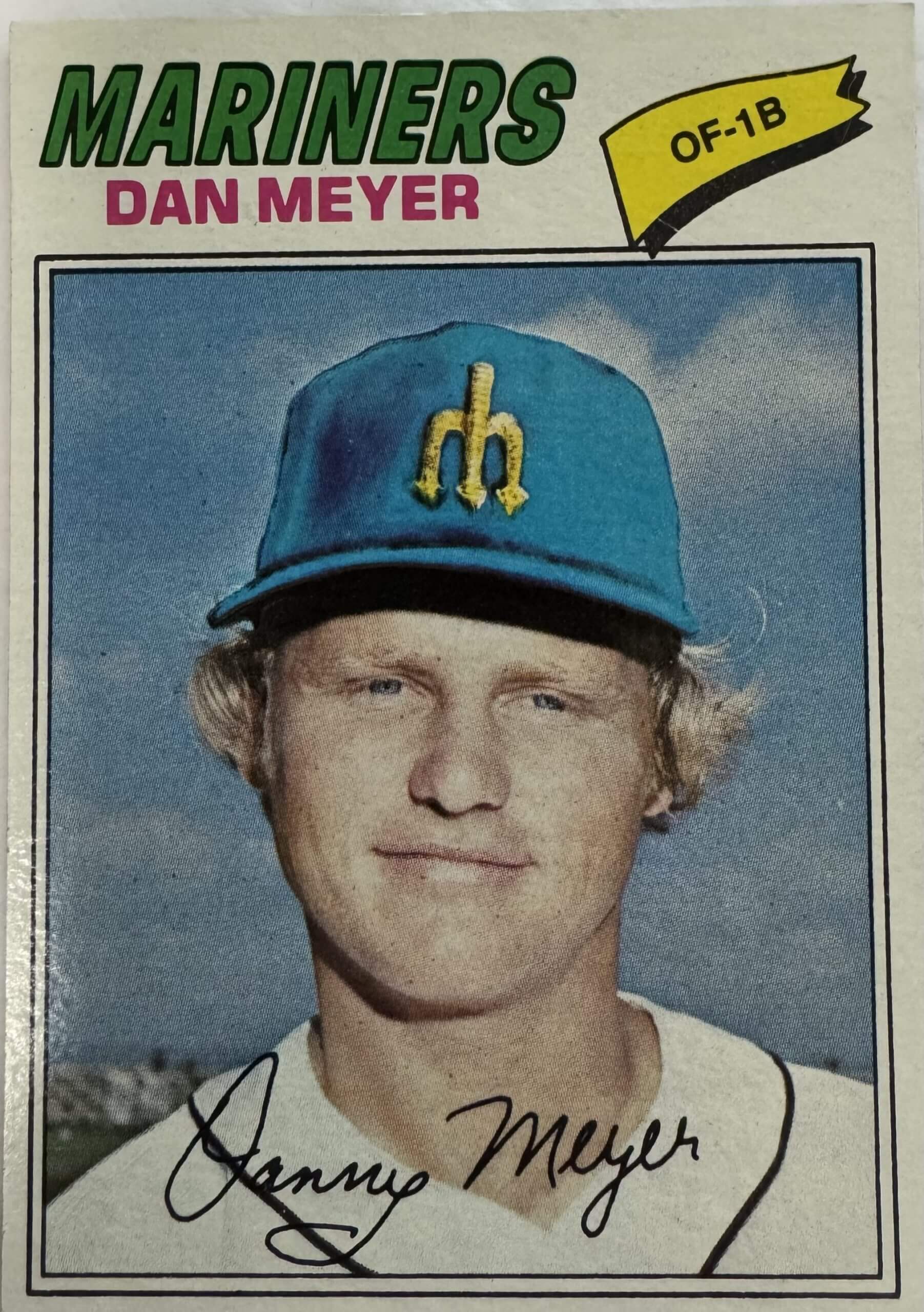

6. Dan Meyer, Mariners, #5271977: .273, 22 homers, 90 RBI

Meyer isn’t modeling a future fashion for the Mariners, who switched to a jersey with stripes down the middle in 1987. He’s shown in the Detroit Tigers’ classic home whites, which Topps didn’t bother to alter. They sure went to work on that cap, though!

Despite an unfortunate -6.4 bWAR for his career, Meyer enjoyed his best season in 1977, with a career high in home runs and RBIs. He played 159 games, one shy of Ruppert Jones (the Mariners’ first All-Star) for the team lead.

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

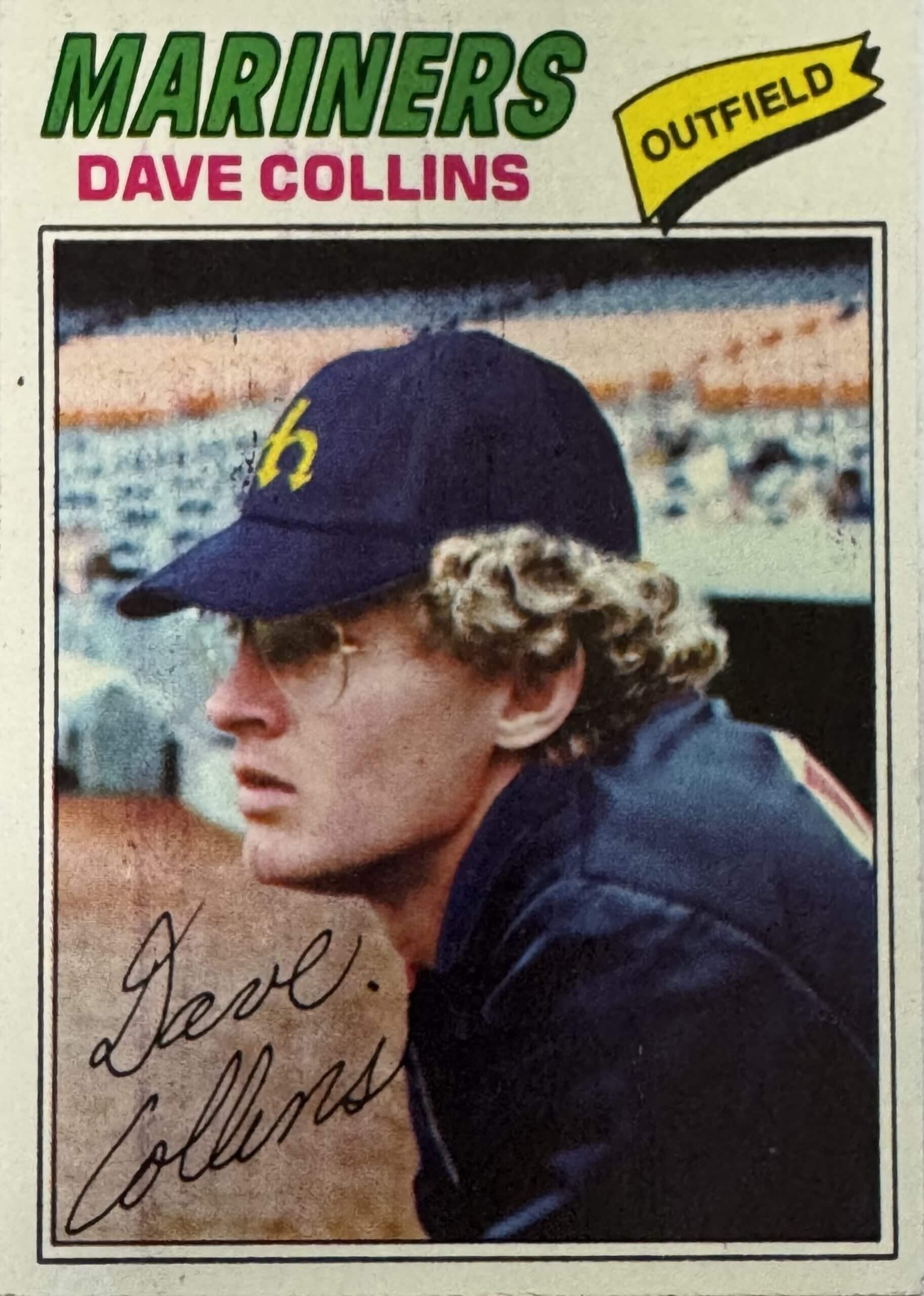

5. Dave Collins, Mariners, #4311977: .239, 5 homers, 25 stolen bases

Dave Collins wore glasses and played for the Angels in 1976 (note the logo on the back of the jacket). But he always had straight, dark hair. Curly, blond locks like The Greatest American Hero? Believe it or not, that’s not him.

Turns out that’s Collins’ Angels teammate, Bobby Jones. (Hat tip: Night Owl Cards). Topps did issue an actual Collins card in 1977, but it was through its Canadian licensee, O-Pee-Chee.

Collins, a reliable speedster, spent just one year with the Mariners, who traded him that winter for Shane Rawley, the future pizza king of Sarasota, Fla. Collins would play 16 seasons and was part of the Blue Jays’ first winning team in 1983.

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

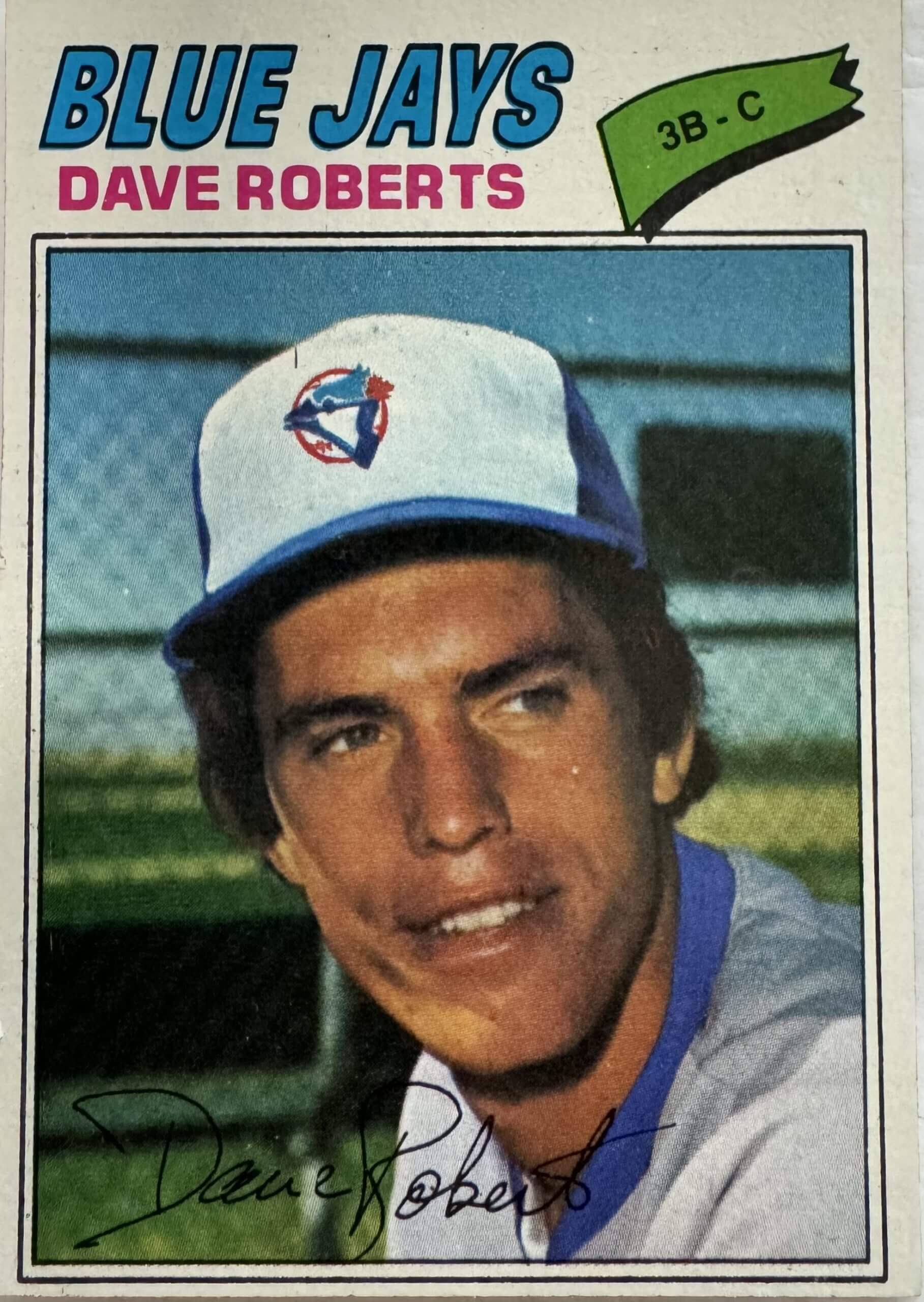

4. Dave Roberts, Blue Jays, #5371977: Traded back to San Diego for reliever Jerry Johnson

Four guys named Dave Roberts have played in the majors, including, of course, the current manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers. This one was the first overall draft pick in 1972 by the San Diego Padres, who put him on their big-league roster immediately.

Alas, Roberts would spend much of the 1970s shuffling between the majors and Triple A, and he never did wear the Blue Jays’ logo, depicted microscopically on his cap. The Mariners traded him back to the Padres for reliever Jerry Johnson before spring training.

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

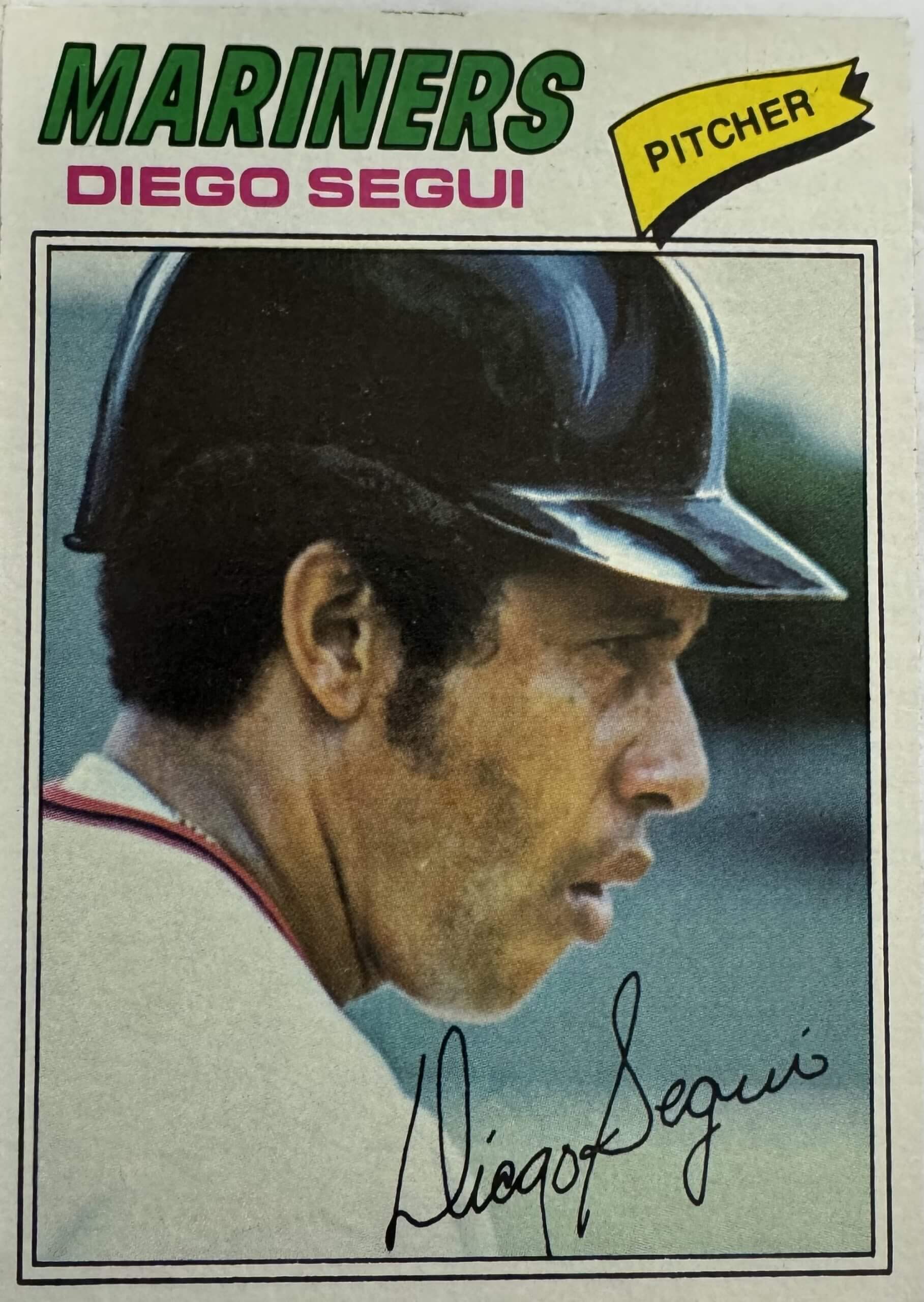

3. Diego Segui, Mariners, #6531977: 0-7, 5.69, 40 games (7 starts)

Gotta admit, I have no idea why Diego Segui would be wearing a batting helmet in this photo. He seems to be wearing a Red Sox jersey, but only played for Boston after the creation of the designated hitter. A spring training game, maybe?

Anyway, Seattle took Segui, who hadn’t pitched in the majors since the 1975 World Series, and gave him the ball for the opening game. It was a nod to the 1969 Seattle Pilots, for whom Segui went 12-6.

His Mariner tenure was a struggle, but when the team played its Kingdome finale in 1999, it tried to bring back Segui for a ceremonial “final pitch” to son David, the team’s first baseman. Flight trouble nixed that plan, so Segui’s seven-year-old grandson, Cory, did the honors instead.

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

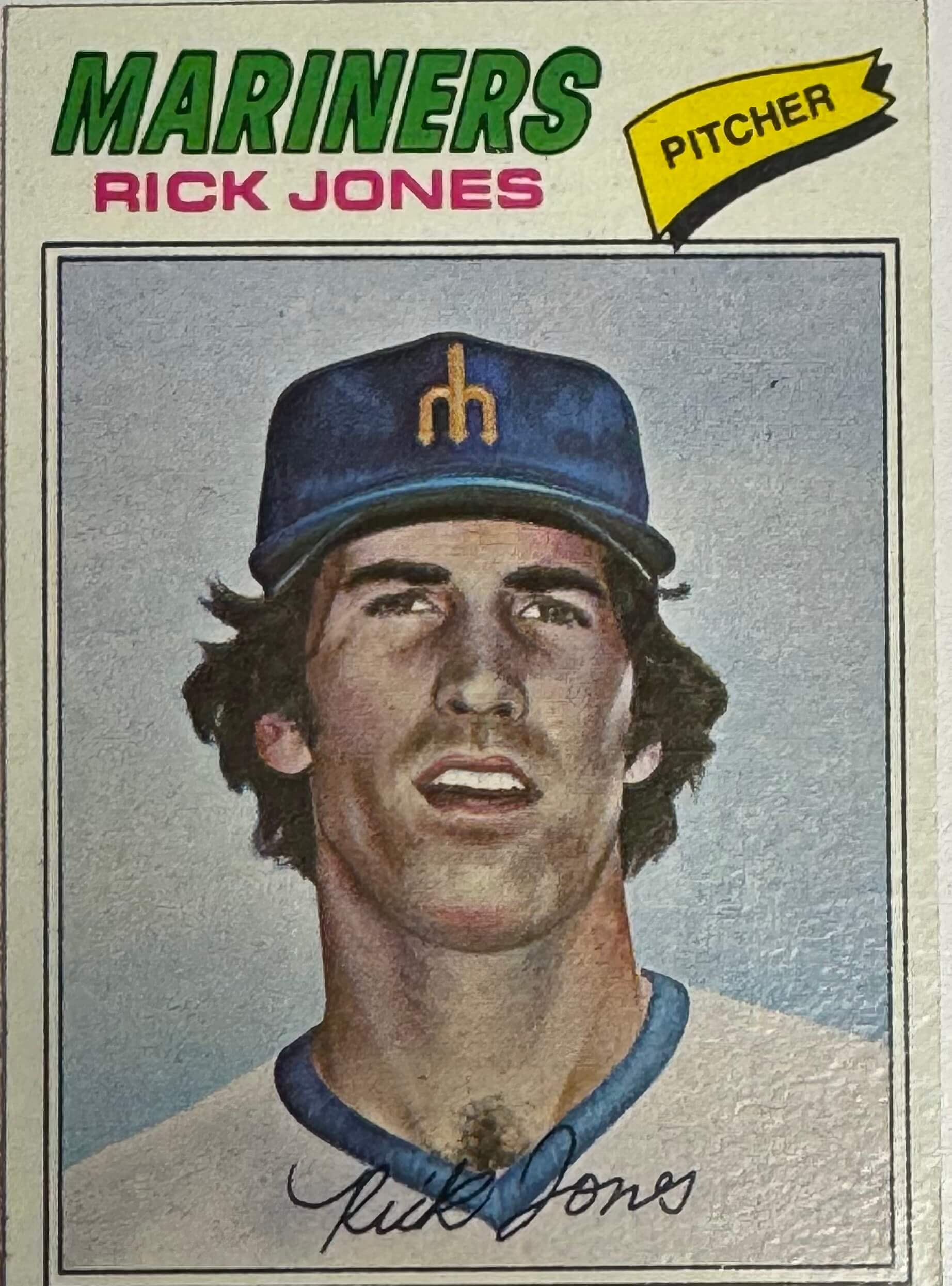

2. Rick Jones, Mariners, #1181977: 1-4, 5.10, 10 starts

This one belongs in the airbrush Hall of Fame, likely taken from a black-and-white photo of Jones when he played for the Boston Red Sox. It’s very creepy, yet oddly mesmerizing.

Seattle chose Jones in the expansion draft, reuniting him with his first Boston manager, Darrell Johnson, who guided the new Mariners. Jones worked 9 1/3 innings, with 11 strikeouts, for his first career victory on June 18 — then blew out his elbow five days later.

“My arm felt like I was shot with a .22,” he said in his SABR bio. “At the time, everything had to go through the team doctor, and they decided to operate on my ulnar nerve. Today, I believe that’s considered Tommy John surgery. I was told I would be OK in about 30 days, but two months later I still couldn’t brush my teeth.”

Jones would never earn another win, or another Topps card.

(Caroline Kepner / Special to The Athletic)

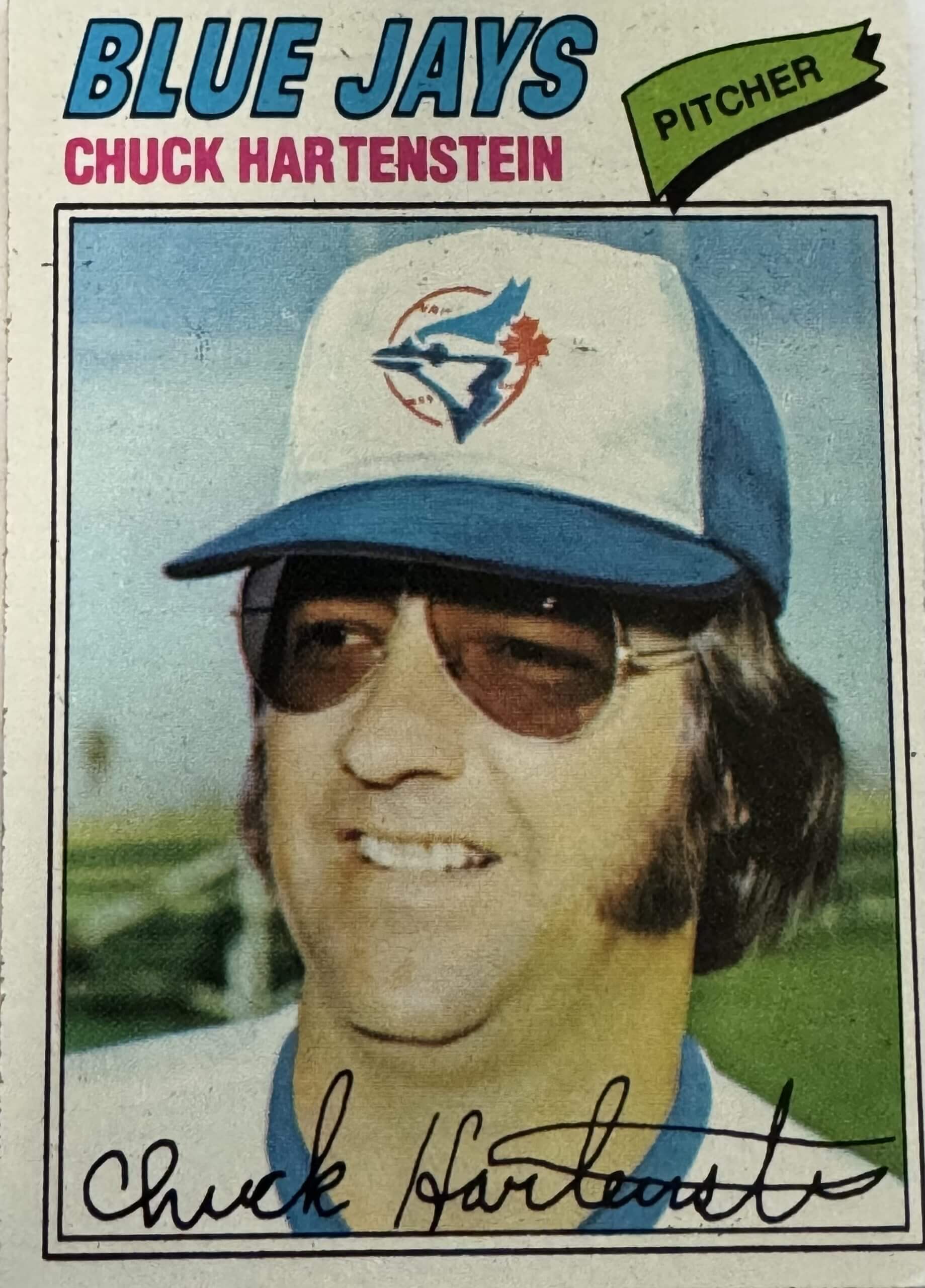

1. Chuck Hartenstein, Blue Jays, #4161977: 0-2, 6.59, 13 games

Elvis Presley died on Aug. 16, 1977, three weeks after his final pitching appearance for the Blue Jays.

OK, maybe not. But much like The King, ol’ Chuck sure changed his style over the years, from a slender, clean-cut Chicago Cub nicknamed “Twiggy” to an airbrushed Blue Jay who looked like the life of the party.

Hartenstein, who had spent parts of five years in the majors, toiled for six full seasons at Triple A before resurfacing with the expansion Blue Jays. They lost all 13 of his appearances, but liked him enough to hire him as a minor-league pitching instructor that September. Hartenstein stayed in the game for decades as a coach and scout — and actually outlived Elvis by 44 years.

“Charles ‘Chuck’ Oscar Hartenstein, Jr. had four great loves in his life — his family, baseball, The University of Texas, and Budweiser,” his obituary began. “Sadly, he said goodbye to those loves on October 2, 2021 at the age of 79.”