ANNOUNCER: NPR.

[COIN SPINNING]

[THEME MUSIC]

DARIAN WOODS: Greg Rosalsky, author of the Planet Money newsletter, ready to pop some champagne?

GREG ROSALSKY: [LAUGHS] Yeah. Why are we popping champagne so early in the week again?

WOODS: It is the economics Nobel. And it’s the one time of the year when I’m allowed to talk about Francis Bacon and the scientific method and the Enlightenment and how that all led to the incredible discoveries and gadgets we have today.

ROSALSKY: I’m so happy for you, Darian. Yeah, so the award, this was a huge win for economic historians, among others, Joel Mokyr from Northwestern University.

JOEL MOKYR: For economics to work without economic history is like an evolutionary biologist without paleontology. And if you don’t have paleontology, you just miss 99.5% of all the species that ever walked this Earth.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

ROSALSKY: This is The Indicator from Planet Money. I’m Greg Rosalsky.

WOODS: And I’m Darian Woods. Today on the show, we’re going to answer the question of why technology keeps getting better and better. Along with Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt got the economic Nobel this year for their work on understanding growth and innovation. So today, we’re going to focus on a part of that– Joel Mokyr’s economic history of the European Enlightenment.

WOODS: In medieval times, there were a lot of pretty cool inventions coming out of Europe– eyeglasses, mechanical clocks, deep plows for better tilling soil. But while these were handy for short-sighted people or people who needed the time or for farmers, the inventions, as a whole, didn’t lead to Europeans getting much richer.

ROSALSKY: Economist, historian, and now Nobel laureate Joel Mokyr described what this time was like on a previous episode of Planet Money.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

MOKYR: Terrible– lots of hard work, backbreaking work, and always a danger of not having enough to eat, threat of famine looming over one’s life every day. A third of all newborns died in infancy or before the age of one– yes, thereabout.

[END PLAYBACK]

WOODS: Grim.

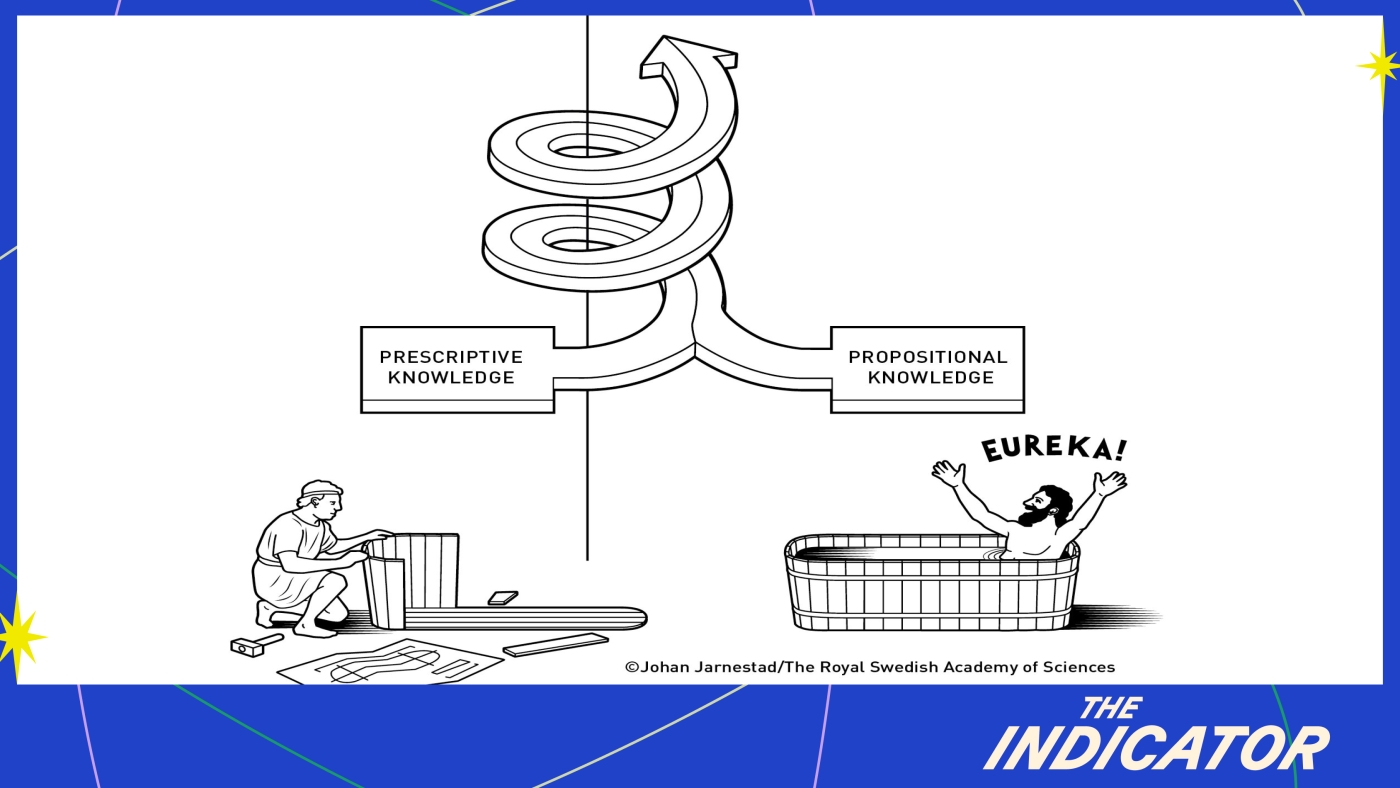

ROSALSKY: Yeah, ugh. Anyway, Joel Mokyr, he says to understand what happened next, you need to put the kinds of knowledge that we produce into two categories. One is what he calls prescriptive knowledge. That’s, like, instructions and mechanics. You know, like, I’m building this cathedral, and, you know, I need this many, you know, load-bearing beams for something this tall with, you know, stove bricks this thick. I’m not writing out calculus equations. I’m not doing, like, you know, big sky thinking. I’m just using the knowledge that has been passed onto me that’s been discovered through trial and error. I probably don’t know why this many beams are needed, you know, just that it works.

WOODS: Yeah, and then on the other side, he has what he calls propositional knowledge, basically laws of nature, things like mathematics and physics. And according to Joel Mokyr, these two ways of learning were kept kind of separate in the Middle Ages. You’d have your masons cutting the stones on the construction site over there and the wonks writing theories with their quill pens over there. But they weren’t really talking to each other. It was basically the book learning wasn’t meeting the street smarts.

ROSALSKY: Then around the 1600s, people like Francis Bacon in England started making waves in science. Bacon encouraged scientists to test their theories, to measure precisely, and to not be afraid of scientific inquiry as somehow, you know, blasphemous. By testing theories in the lab or out in the world, this brought together propositional and prescriptive knowledge.

WOODS: Yeah, and it all kind of seems obvious now, but Joel Mokyr argues that this feedback loop between theory and testing allowed for products to be refined and improved. One example is that by understanding atmospheric pressure, the steam engine could be made better, meaning more efficient motors.

ROSALSKY: There’s another great thing about bringing propositional knowledge into practice. It’s– having an explanation about how the world works, it just kind of makes your ideas more persuasive. If you just tell all the doctors to start washing their hands, they might be like, why? And you’re like, I don’t know. It just seems like it works better. But if you actually have, like, an explanation, like, tiny organisms and, you know, gunk called germs and bacteria, those cause diseases, your knowledge might actually run into less resistance.

WOODS: OK, so theory and practice married together at last in this scientific revolution. But there is more to it. Joel Mokyr emphasizes that a country’s openness to change is a key ingredient for sustained economic growth. Almost by definition, the people on top are doing pretty well from the existing technologies, and so new technologies and businesses could be a threat. In the United Kingdom, the British Parliament as we know it today started in 1800. And this gave a voice to a broader array of people. It meant that people who could benefit from, say, more railroad connections could advocate for constructing them, even if it might be disruptive to existing businesses. The not so optimistic take, though, is that there is no obvious trend that institutions get more open to growth over time. At his Nobel press conference yesterday, Joel recalled a conversation from his colleague, Douglass North.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

MOKYR: There is no way that we can show that they get better over time. They do go up. They do go down. I mean, there are periods in which institutions all over the world were getting remarkably worse, particularly the interwar period in the 20th century, say. And it seems that there’s some evidence to show that that’s what’s happening today.

[END PLAYBACK]

ROSALSKY: Yeah, this is all kind of starting to remind me of debates we’re having today. I’m thinking also about the Trump administration’s efforts to revive the coal industry. Coal in the US is being largely supplanted by natural gas and renewables for new capacity, largely because of improving technology in these areas. That’s maybe cold comfort, though, for miners living in Kentucky or West Virginia.

WOODS: Yeah, the price we pay for progress is bankruptcies, layoffs, and dislocation. While the world as a whole is better off in the long run, there are costs, like in AI. A lot of the Hollywood writers’ strike was about whether movies and TV shows should be allowed to use artificial intelligence. You’ve got a technology that speeds up part of the writing process, but vested interests, like the writers’ union, don’t want that technology being used. Joel said at the Nobel press conference that that’s because all technologies have side effects and can sometimes do harm.

ROSALSKY: That said, Joel is definitely not an AI doomer.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

MOKYR: Machines don’t replace us. They move us to more interesting, more challenging work. And as AI moves us up to take these jobs over, people will move to even higher jobs.

[END PLAYBACK]

WOODS: Joel Mokyr thinks that this world of sustained progress that we’ve gotten used to is fragile. In his book Lever of Riches, he wrote, “By and large, the forces opposing technological progress have been stronger than those striving for changes.” He says, “Technological progress is like a fragile and vulnerable plant whose nourishing is not only dependent on the appropriate surroundings and climate, but whose life is almost always short and can easily be arrested by relatively small external changes.” So he’s basically saying that this kind of economic growth can’t be taken for granted. But, he says, how we decide to use those technologies can have very different outcomes.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

MOKYR: You make a hammer. You build a technological tool. You know, it can be used to build a home, and it can be used to bash Abel and Cain’s heads in. That’s, I think, something that’s true across the board for technological change throughout the ages. Gunpowder can be used to fight wars, and it can be used to build tunnels. And I think the same is true for the things that are on the horizon today, including artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and so on and so forth.

[END PLAYBACK]

ROSALSKY: And Joel, he’s betting we need technological advances to solve some of the biggest issues we’re dealing with today.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

MOKYR: The human race faces two of the greatest challenges that it has ever faced. And those are climate change and demographic change. But given that the only way in which we can cope with this crisis is inventing ourselves out of it, I strongly urge the world to keep putting effort and money and resources and incentives to the people who are trying to invent us out of these two crises.

[END PLAYBACK]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

WOODS: By the way, if you want to read more about the economics Nobel, you should check out Greg’s newsletter, npr.org/planetmoneynewsletter. That’s npr.org/planetmoneynewsletter. This episode was produced and fact-checked by Julia Ritchey. Engineering was done by Patrick Murray. Kate Concannon edits the show. And The Indicator is a production of NPR.

Copyright © 2025 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

Accuracy and availability of NPR transcripts may vary. Transcript text may be revised to correct errors or match updates to audio. Audio on npr.org may be edited after its original broadcast or publication. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.