Signed 190 years ago today, He Whakaputanga still defines the Māori struggle for mana and self-determination.

The very first Māori dictionary defines “Whakaputa” as – “to boast or make visible”. This core context reflects the ancestral mentality that He Whakaputanga physically manifested to the world.

Growing up in Te Tai Tokerau, I took for granted the general awareness of He Whakaputanga. This document, alongside te Tiriti o Waitangi, forms a significant part of the northern indigenous identity, as well as the story of Māori sovereignty in Aotearoa.

Only in moving to Pōneke to study Pākehā law did I realise the tuakana document to te Tiriti was not well-known south of the Kaipara. I was sometimes mocked by my southern counterparts about Ngāpuhi being the iwi that never ceded sovereignty – I never understood why that was funny. I now understand those jokes came from people who didn’t know about He Whakaputanga and its purpose, which is inextricably linked to the purpose of te Tiriti.

I didn’t grow up knowing the details of this watershed constitutional document. But the image of Te Kara, the pictorial representation of Māori sovereignty, has never faded from my memories. Every year, I would go to Waitangi as a haututū kid where my priorities were kai and the rides. Now a haututū adult, I understand the depth of the whakapapa behind He Whakaputanga, a declaration of the sovereignty of the United Tribes made 190 years ago.

The whakapapa of the mana that underpins both He Whakaputanga and te Tiriti starts with the first arrivals to Aotearoa from Hawaiki, including Kupe in Te Puna i Te Ao Mārama, about a thousand years ago (give or take, though my Hokianga relations might disagree with me on this – kia ahatia).

The oratorical fibres of He Whakaputanga began to form at least 15 years prior to the initial signings at Te Tou Rangatira in 1835. Ngāpuhi rangatira Hōngi Hika and Waikato visited England in 1820, where they discussed a number of matters with King George, stemming from growing concern at the Bay of Islands around the behaviour of unruly Europeans and traders. Rangatira of the north wanted to regain control over the Bay and be able to punish the transgressions of foreigners, so they presented a list of demands to the king reflecting a desire for some certainty of control over the European intrusion.

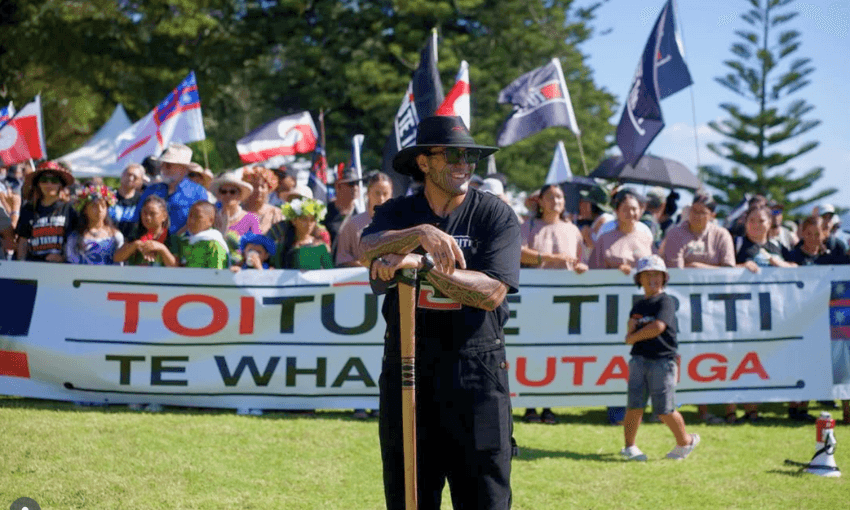

Ngāpuhi chiefs gathering to choose the United Tribes flag. Many would go on to sign He Whakaputanga. (Image: Shaw Savill, Alexander Turnbull Library)

The next decade saw a number of wānanga in Te Tai Tokerau, including the first meeting of Te Whakaminenga – the confederation that would eventually create He Whakaputanga – at Te Ngaere, around 30 kilometres north of Waitangi.

In 1831, 13 Ngāpuhi rangatira signed a letter of petition written by young academic protégé Eruera Pare, repeating the concerns raised in person to King George, who had failed to meet the demands made by Hōngi. Three years later, a national flag known as Te Kara was selected to resolve trade access issues, and the following year He Whakaputanga was born.

This whakapapa is important as it disproves the theory promoted by some that He Whakaputanga was a pet project of James Busby, who only came into the picture three years before the signing. He Whakaputanga was an action carefully discussed and taken through the agency of rangatira who were acutely aware of the need to protect their mana from a changing world. This document did not create their mana, but found ways to describe it in a language and format the foreign mind could understand, and not deny. The US, France and Britain all recognised He Whakaputanga by the turn of the following decade.

Importantly, He Whakaputanga was not an agreement between multiple parties. It was one party, Te Whakaminenga, making a declaration that all “kīngitanga” (a modern political extension of mana) in respect of hapū territories resided with them. They also agreed to meet annually at Waitangi to exercise their exclusive right to frame ture or laws for the purposes of justice, peace, good order and trade.

To think the same collective of hapū would give away the rights they declared to the world only five years later is unfathomable. The fact the hapū of the north never ceded sovereignty is not a joking matter – it is a generational legacy that defines a purpose as kaipupuru, or protectors of that truth.

Heoi anō, He Whakaputanga should be open to all rohe to use as evidence of undying rangatiratanga. All hapū, no matter their rohe, possessed (and still possess) the prerogative to declare their mana to the world. However, many rohe did not feel the same settler pressures as those in Te Tai Tokerau, hence why the north was the first to do so.

He Whakaputanga set the stage for te Tiriti, which extended the declaration by giving rights of self-government to settler peoples in Aotearoa, while maintaining rangatiratanga of hapū across Aotearoa. Signatures to te Tiriti can also be found in He Whakaputanga.

Embracing the declaration together can only galvanise our intent in pursuing change for Aotearoa, based on the reality that our mana and reciprocal duties as tangata whenua have never wavered. He Whakaputanga provides a roadmap for such change: a return to the hapū-centric system its words were designed to protect. The document was built to sustain and guarantee the rights and responsibilities traditional communities had possessed and practised for generations.

Born out of imperialism and capitalism, the centralisation agenda of the British Colonial Office has forced us to forget the power of – and need to return to – community. The current model that anchors everything in Wellington offices does not work for tangata whenua.

He Whakaputanga was the first pou in the ground making our presence known to the globe. Te Tiriti was the second pou to its side, which then created a waharoa – a doorway welcoming all cultures and people to these lands on the basis of mutual benefit, and the condition of respecting the mana of tangata whenua. Two centuries later, both pou must be seen as working together, and we must restore their vision of what Aotearoa was meant to look like.