With Aoteaora on the ‘cusp’ of another serious measles outbreak, Emma Gleason finds out what happens when you catch it.

Measles is spreading again. Thirteen cases have now been confirmed in Auckland, Wellington, Manawatū and Nelson, and with thousands of close contacts identified, more are anticipated. There’s also a second, unrelated cluster in Northland, with 12 people affected. Experts are warning we’re on the “cusp” of another serious outbreak.

Our biggest in nearly two decades was in 2019, which saw 2,213 people contracting the disease and 35% of them hospitalised. Another big year was 2011. More than 550 people caught measles, and my father was one of them.

At first he thought he just had the flu. He tried to sleep off the body aches in the work sick bay before going home, where he got sicker and sicker. “I woke up a few mornings later with a rash all over,” he remembers. He went straight to the A&E where the doctor tested for measles. Diagnosis confirmed, he was asked to vacate the clinic immediately due to the contagious nature of the disease, advised to go home and “stay home”, drink plenty of fluids and keep a close eye on his temperature.

My dad was caught up in the large Auckland outbreak, which saw community transmission and 467 cases. It was one of six measles outbreaks in the country that year, with “the highest number of outbreaks and cases reported for measles since reporting began in 2001” (this was eclipsed in 2019).

“I was surprised,” he says. “And feeling very sick.” He thought he was immune, and assumed he’d contracted the disease as a child, like many members of his generation who were born before immunisation. “In the USA where I was born there were no vaccinations, and the neighbourhood relied on children’s parties to enforce immunity for the usual communicable diseases. Family history wrongly said that I had already had measles as a child,” he explains, “I obviously did not catch it way back then.”

It was a similar situation at that time in New Zealand. People born prior to 1969, when the first measles vaccine arrived, are generally considered to be immune to the disease already, likely infected in childhood.

Measles is highly contagious. Non-immune people have a 90% chance of catching it if they’re in the same room as a case. Te Whatu Ora sent my father a letter instructing him to isolate for two weeks and avoid work and social engagements. “I had no interactions with anyone.”

At home, his condition began to deteriorate. “I got worse, and my memory of an entire week is basically gone,” he says. “That was the worst period.” His temperature hit 40 degrees. “I became incoherent and totally debilitated. All I remember retrospectively are the strange dreams involving being on space ships and a dominant recurring dream of being in a large cave with a continuous sound of dripping water,” he recalls. He was later told he’d been wandering around different rooms, disorientated from fever. “After a week my temperature dropped and I started becoming coherent again.”

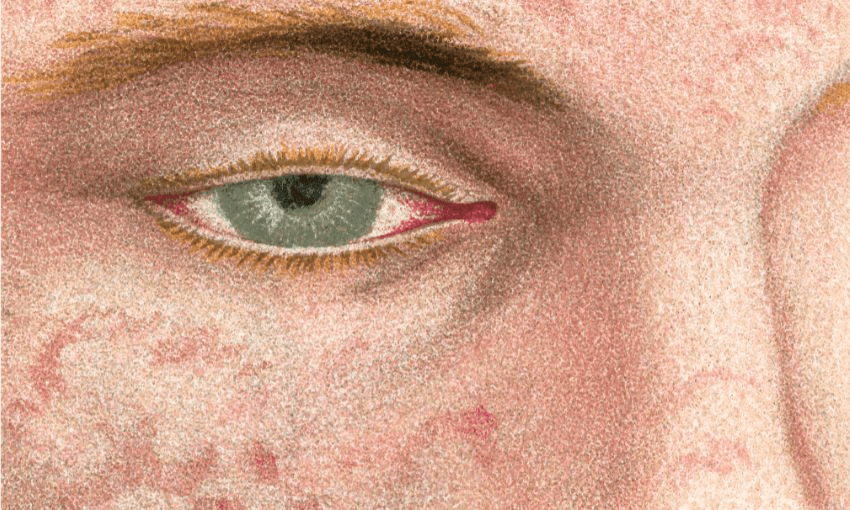

As sick as he was, he’d been told not to go to the hospital if he could help it, due to risk of transmission, and isolated at home instead. His own GP was notified of the diagnosis by letter later. “I saw him a week or so after it was all over,” my father says. “He told me that I had it really bad.” Some symptoms lingered. “I had sore eyes for a long time afterwards.” The body aches continued too, and there were nerve issues. Eventually, though, he came right. Not everyone does.

Seven people died in 1991, and though our outbreaks are becoming less deadly, studies show people who contract the disease have an increased risk of other unrelated infections. Adults over the age of 20 are more likely to suffer complications from the disease, as are children under five. Pregnant women are high risk – two unborn babies died in 2019 – and anyone with weakened immune systems, like my dad.

More cases have been confirmed in the current outbreak, and locations of interest include multiple high schools.

“Contracting measles as a child, let alone an adult, is not something you would wish on anyone,” he tells me. It was the sickest he’s been in his entire adult life. “I understand I was one of the oldest people in Auckland at the age of 57 to contract measles, although this was soon overtaken that same year by some older person.”

He’s not alone in reaching adulthood without acquiring immunity, though cases in people over 50 are rare (1% of the 2019 outbreak). Te Whatu Ora cautions against relying on “your own or anyone else’s memory”. Common symptoms – cough, fever, runny nose – are shared by other diseases, and have resulted in mistaken diagnoses in the past. You may think you’ve had measles, but won’t know for sure unless you have serology results or your immunisation records.

The combined measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine was introduced in 1990. Doses are given to babies at 12 months and 15 months under the National Immunisation Schedule – it’s also free for anyone under 18 – but our vaccination rates are at an “all-time record low”.

Of the nation’s two-year-olds, 82% are fully immunised, a stat that drops to 80% for New Zealanders born in the 1980s and 1990s.

A 1991 outbreak saw tens of thousands contract the disease. But after years of strong immunisation rates, New Zealand was declared free of endemic measles by the World Health Organisation in 2017. Two years later 2,213 people caught the disease. If our numbers aren’t curbed by next year, WHO will likely withdraw our elimination status.

Herd immunity requires 95% of the population to be vaccinated, and our collective immunity is currently “too low to prevent outbreaks from happening”, according to Te Whatu Ora. Without it, community outbreaks will continue. Modelling predicts this current outbreak could reach 150 cases a week, larger than the 100 Health New Zealand says it can cope with, and it’s urging people to get immunised. Whether through complacency, ignorance or forgetting what past epidemics were like, Dad doesn’t think people take measles seriously enough. Experiencing it firsthand “reinforces my strong belief in widespread enforced immunisation for all communicable diseases” and he’s of the opinion that “immunisation should cover the entire population without exception”.